In Grandmother’s House

Bergman on Unto My Fear.

About the text

In the programme to Bergman’s play, he describes how the main character Paul’s background is very similar to Bergman’s own grandmother’s apartment in Uppsala, a milieu that he would turn up again a much later, and much more well-known, piece.

What follows is a description of my grandmother’s apartment, where the drama unfolds. My grandmother lives in a university town and parish seat in the middle of Sweden, in a little two-story stone building with the the street called Allégatan on one side, and the cathedral on another. During the summer, it’s a verdant place. The windows open up to a spacious courtyard, which connects to the street through a fourteen-meter long cobblestone archway. The courtyard is a playground for children, cats, rats and small birds, twittering in the bushes. There are two large carriage houses, as well as the house’s six privies. In a hole in the ground in the middle of the yard there lives a Jew in a sort of underground store. It’s said he’s unkind, even little dangerous. I don’t know for sure.

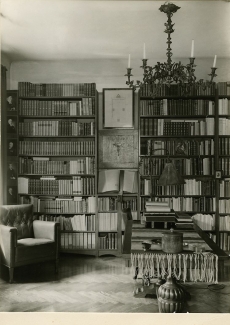

Grandmother’s apartment is enormous: second floor, entrance from the courtyard. There’s the dining room, drawing room, the vestibule with a firewood bin and stained-glass windows, a large kitchen with a serving room and icebox with a fastidiously whitewashed drop-leaf table by the window. There’s the servant’s quarters, Grandmother’s bedroom, the guest room, Grandfather’s workroom (Grandfather is dead). Then there’s the creaky stairs up leading up to the attic, always squeaking and whispering. And there’s all the nooks and crannies filled with secret whispering, delights and strange things. The tiled stoves, roaring with warmth during the winter. The statuettes which almost seem to come alive in the quiet sunlight. The sunlight which almost sounds like a note if you happen to be alone – by which I mean without people around. You’re never truly alone in an old house. The carpets, which are old beyond counting and a little worn, the heads in the moulding, the paintings of Venice and Florence. The prisms of the chandeliers. The window shades covered with palaces and princes, princesses, dragons, landscapes. The gas-lamps outside which give life to everything at night, and create ships and forests and strange things that move upon the ceiling, and when the wind blows there comes a storm upon this sea of shadows, everything fluctuating, flowing. The wallpaper’s patterns could form queer faces, though they were never dangerous; the furniture could be as large and heavy as the beasts of the jungle, or as light and delicate as those of noble extraction.

A red ball was firmly lodged behind the sofa.

And then there are all the clocks. In every room there are at least two, and they’re all in motion, poking, prodding, ticking, thinking, speaking.

As should be obvious, this is a very peculiar house, filled with mysteriously sneaking, ticking, whispering life. (I don’t mean that it’s haunted. There’s one ghost, but he lives in the attic and never comes out.) I mean the life of the walls, the furniture, the clocks: the life of things.

I was quite small the first time I visited her apartment. After that, I haven’t returned, which is why I’ve described it through the eyes of a child. But I believe that if the house should suddenly reappear, the adult me would stand there in the quietness, listening to the clicking of the clocks and the spring breeze rustling through the elms outside, to the sun’s silent flickering, and to the stately side-board’s never-ending stories about the tiny people living within its depths.

Unto My Fear, program notes, Göteborgs Stadsteater, 1947. Later published in Röster i Radio, No. 10, 8-14 March 1953, to coincide with Bergman’s radio production.