An unrequited love of music

Exclusive essay by Charlotte Renaud on Bergman's relationship to music.

"If I had to choose between losing my sight or hearing – I would keep my hearing. I can't imagine anything more horrible than to have my music taken away from me."Ingmar Bergman

An unrequited love of music

'If I was forced to choose between losing my hearing or losing my sight, I would keep my hearing. I can think of nothing worse than having music taken away from me.' This confession by Ingmar Bergman is rather surprising, coming from a filmmaker renowned for the astonishing beauty of his imagery. His 1975 version of Mozart's Magic Flute is, however, one of the most wonderful examples of this passion for music. Other examples come through in his various opera productions, including Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress, staged at the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm in 1961, and Börtz's The Bacchae, 30 years later. Nevertheless, the silver screen is where we truly witness Bergman's impassioned devotion to music, with its central placement in his films and the way in which he borrows countless elements from the classical repertoire.

Many books have been written about Bergman, some of which speak of this infatuation. Bergman himself spoke extensively of music. This essay attempts to comprehend the indispensable role music played throughout his career – from Crisis to Saraband. Throughout this study, it becomes clear that Bergman was not only a music-loving filmmaker, but also a true master of sound. For him, the art form closest to cinema was neither drama nor literature, but music. What do music and film have in common? What role does Bergman appoint music in his films? How does music affect the very act of creation? Musical references are rarely listed in the credits, with occasional mentions of the composer. The first step of this work has therefore been to identify the musical pieces, listed here on the left.

Bergman's passion for music manifests itself very early on in his work. Music in Darkness, from 1948, tells the story of a young pianist left blind in a shooting accident. To Joy (1950) tells the misfortunate tale of an ambitious violinist. Summer Interlude (1951) recounts the life of a ballerina at the Stockholm Opera. Excerpts from Beethoven, Mozart and Mendelssohn appear in these films. Between Waiting Women and The Virgin Spring, musical references become more sparse and limited to piano pieces: Schumann, Liszt and Chopin in Smiles of a Summer Night, Bach in Wild Strawberries, and Scarlatti in The Devil's Eye. Original compositions were more commonly featured during this time.

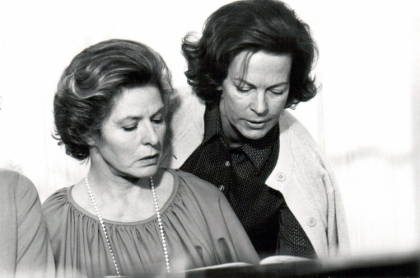

Mai Zetterling and Birger Malmsten in Music in Darkness.

Photo: Bengt Westfelt © AB Svensk Filmindustri

The situation shifts with Through a Glass Darkly. In this 1961 film, the saraband from Bach's Cello Suite No. 2 appears four times, while original compositions have completely disappeared. Nothing remains, except for Bach. From this point on, Bergman's usage of classical music becomes increasingly more important, through to his final film, Saraband, in 2003. This brief timeline enables us to classify the various uses of musical pieces in Bergman's works, uses which appear to increase over time towards more and more musicality.

Contextual and Structural Uses

Music can serve either to intensify or signify an emotional moment. When Martha gives birth in Waiting Women, her happiness is highlighted by Gluck's Dance of the Blessed Spirits. On the other hand sadness is brought to the forefront in Music in Darkness, when Bengt, the young blind man, plays Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata and a Nocturne by Chopin. He plays in the dark (both literally and figuratively), giving resonance to the titles of the chosen musical pieces. These musical masterpieces from the Romantic Period perfectly convey his loneliness and are superbly appointed in their role as “emotional factors”. This use of musical referencing remains very conventional. Furthermore, Bergman seems to parody himself a few years later in Smiles of a Summer Night, when Henrik, dejected by his emotional misfortunes, rushes to his keyboard to pound out passionately short and very well appropriated excerpts from Chopin (Impromptu), Liszt (Dream of Love) and Schumann (Soaring).

Music is also a means of conjuring up the past, often in a rather nostalgic manner. For instance, in Summer Interlude, when speaking about Marie's late mother, Uncle Erland accompanies himself with a Chopin Impromptu; when Marie goes back to the island where she fell in love for the first time, we hear one of Chopin’s Etudes. Music also plays a role in Wild Strawberries, when Isaac dreams that his cousin marries another man, for whom she plays a Bach Prelude. Dreamlike scenarios in Bergman’s films are often accompanied by Bach or Chopin, but another example is when Jacobi arrives to free Fanny and Alexander from the bishop. This episode is paired with the seventh movement of Britten's Cello Suite No. 3, aptly entitled Recitativo Fantastico, and the same suite accompanies Oscar's ghost as he visits his mother. When it resounds, music both accompanies and strengthens the narrative dimension.

In Bergman’s work, music also plays a structural role. The number of films which start and finish with the same musical piece is striking: Prison (a Bach cantata), To Joy (Beethoven's Symphony No. 9), Summer Interlude (Swan Lake), The Devil's Eye (a sonata by Scarlatti), Through a Glass Darkly (Bach's Cello Suite No. 2), All These Women (Bach's Orchestral Suite No. 3), Cries and Whispers (a Mazurka by Chopin), Fanny and Alexander (a quintet by Schumann), In the Presence of a Clown (Schubert's Winterreise), and so on.

By using the same music at both the start and finish of a film, perhaps Bergman is hoping to use an inclusive structure to enclose the film in its own temporality, to come full circle, to put the closing bracket on the thought he began at the opening credits. By isolating the film, music turns it into an object in itself, with its own individual intelligence. In To Joy, the music determines the very dynamic of the narrative, instilling it with meaning – for example, the orchestra in which Stig plays is rehearsing Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, when he learns that his wife has been killed in an accident. The film is a long flashback during which he recalls the years they spent together. At the end of the film, he returns to play in the orchestra, and seems to overcome his grief when the choir sings Ode to Joy. The conductor hands us the very key to the film when, as the musicians are preparing to rehearse the final bars of the symphony, he says to them, “This is an outburst of joy. Not one that results in laughter or proclaims, 'I'm happy'. I'm talking about an immense overwhelming joy, beyond pain and infinite grief. An incomprehensible joy!”

Stig Olin and Victor Sjöström in To Joy.

Photo: Louis Huch © AB Svensk Filmindustri

Summer Interlude, which was released directly after To Joy, uses Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake in the same manner. Marie plays the role of Odette in Swan Lake, and is liberated by love, just as Odette was. The film starts at the dress rehearsal of the ballet and ends on the opening night. Throughout the film, the young woman revisits her past and rediscovers her interest in life. Music can also be used as a structure within the film itself, in order to highlight the most important moments. In Through a Glass Darkly, for example, the saraband of Bach's Cello Suite No. 2 appears four times: in the opening credits; after the first third of the film, when Karin discovers her father's diary; after the second third (the incest); and at the very end, when the helicopter carries Karin away. Each and every musical placement also delimits a different section of the film, and structures it in three parts of equal duration. In the same vein, Fanny and Alexander uses Schumann's Piano Quintet on four occasions.

The leitmotif plays the role of a temporal landmark in the narrative flow, a landmark that is more adaptable and unpredictable than the one provided by objective time (from a watch or a clock), but nonetheless equally effective. Michel Chion, in a book on film music, notices that the leitmotif “provides to the musical fabric a kind of elasticity of slippery fluidity”. He adds, “It also seems to generate anxiety and obsessiveness,” which is particularly striking in In the Presence of a Clown, where the last Lied of Winterreise appears seven times. This Lied was composed by Schubert in 1827, a few months before his death, and the hurdy-gurdy player complains, “No one wants to listen/ No one takes a scan/ And the dogs all growl/ Around the aged man.” This work depicting loneliness is reduced by Bergman to its introduction, repetitive and incessantly played in moments of anxiety, and becomes an ominous refrain. On three separate occasions it foreshadows the arrival of the white clown, the incarnation of Death, and concludes the film on Carl's final words, “Man is indeed sinking.”

Bergman sometimes even uses the same musical piece in various films. Such is the case with Bach’s Partita, heard in Hour of the Wolf, and then again in both Shame and The Passion. These three films, shot with the same actors (Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow), were often considered a trilogy of despair. The reappearance of the Partita strengthens this assumption.

Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann in Shame.

Photo: Roland Lundin © AB Svensk Filmindustri

Conversely, the leitmotif can have a playful dimension. In The Devil's Eye, three different sonatas by Scarlatti appear around 10 times. Each one seems to represent a character: the famous Sonata in E-Major introduces us to Don Juan's world; the delicate pastorale accompanies the scenes with Britt-Marie; the Sonata in D-Major, full of pizzazz, resounds with each trick played by the demon watching over Don Juan. Throughout Bergman’s films, there are numerous malevolent references to the genre of classical music.

When Raoul turns up at his mistress’ in Thirst, he has no idea that his furious wife is waiting there. The tune he is whistling is precisely the one sung by Figaro in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, to warn Cherubino that his love affair has been uncovered. In Smiles of a Summer Night, Frederik's nightly visit to Désirée is interrupted by his rival's arrival. To keep up appearances, Frederik hums an air that happens to be the same one Don Giovanni tries to seduce a young bride with in Mozart's opera. But it is in All These Women where Bergman draws the most outright parody. The aria of Bach's Orchestral Suite No. 3 – a slow, lyrical and expressive movement –appears six times, in rather short spurts at diverse moments. The filmmaker deconstructs and manipulates the musical score, treating it like a jigsaw puzzle. He also plays with musical registers. In the beginning of the film, when Cornelius arrives at the famous cellist’s home, he is playing the aria for a group of women. Momentarily distracted, the critic knocks down a statue of the Master. The aria is thereby immediately followed by a spirited ragtime, placing a comic contrast against the dampened atmosphere of such an intimate concert.

Metaphorical Uses

As in Music in Darkness, musical citations in Summer Interlude are intertwined with an original film score, which highlight certain passages, such as the discovery of Henrik's diary, the return to the island, or the memory of the accident. On the contrary, in Through a Glass Darkly (1961), music is almost exclusively borrowed from the classical repertoire and confined to specific moments. This film can be viewed as a turning point in the way Bergman borrows music, which is certainly linked to his marriage to the concert pianist Käbi Laretei, which took place in 1959. As he himself says, “I dedicated this film to my wife at the time. I was beginning to really enter into the music as a professional does. Through a Glass Darkly was affected by my almost daily association with music.” This deepening relationship to music becomes obvious in Bergman’s successive films, in turn developing his listening abilities.

Michel Chion, previously cited in this essay, distinguishes between the “screen music”, which comes from a source that is present or suggested in the action, and the “pit music”, which comes from a source that is imaginary and not present in the action. What is striking in Bergman's films is that for the most part, the music falls into the “screen music” category. The filmmaker seems to take pleasure in filming the performance of a piece of music by its interpreter: the pianist in Music in Darkness; the violinist and orchestra in To Joy; Uncle Erland in Summer Interlude; Cousin Sara in Wild Strawberries; the concert pianists in Hour of the Wolf, Face to Face and Autumn Sonata; the cellist in this film; the aunts in Fanny and Alexander, as well as the bishop and his flute; the pianist in In the Presence of a Clown; Karin and her father, playing Bach at the organ and cello in Saraband. There are very few other instances of films featuring so many musicians playing on screen. When no one is playing, the music is heard through a radio (The Silence, Persona, Shame) or a gramophone (Summer with Monika, All These Women, Saraband). In all these instances music is present on two levels, both on screen and in the narrative.

Käbi Laretei instructing Ingrid Bergman on the set of Autumn Sonata.

Photo: Arne Carlsson © AB Svensk Filmindustri

Consequently, Bergman’s musical references are almost always literal. He never distorts them. He only takes the liberty to simplify them when required by the screenplay. Such is the case in Shame, when Jan wakes up humming a melody from one of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos, and also in In the Presence of a Clown, when Schubert’s Ninth Symphony is simplified onto just a piano, as the main characters have nothing more than that to tell the story of the composer’s life. This simplification also takes place in Fanny and Alexander, when nothing more than a flute is featured in Bach's Sonata No. 2 for flute and harpsichord. But for the most part, Bergman cites the musical works accurately. Bach's pieces are played on period instruments. The Goldberg Variations in The Silence, for instance, are played on harpsichord, as recommended by the cantor himself, as are the Scarlatti Sonatas in The Devil's Eye, (regardless of Käbi Laretei's reluctance to play out of her fear that she was not as competent on the harpsichord as on the piano).

In The Silence, musical usages last for exactly three minutes and 16 seconds. During that time, the action is suspended, the dialogue is interrupted, and real noises are erased. One should not only hear the music, but listen to it – the spectators' faces are shot close up as the overture resounds in The Magic Flute, as are those listening to Mozart's Fantasia in Face to Face or the final Schubert sonata in In the Presence of a Clown. Many other captivated listeners appear throughout Bergman's films: the sisters in The Silence, Elisabeth in Persona, the demons in Hour of the Wolf, the couple in Shame, Carl in In the Presence of a Clown, or Johan listening at full volume to the scherzo of Bruckner's Symphony No. 9 in Saraband. Bergman sometimes comments on the music through his characters. In Hour of the Wolf, the demon Kreisler presents the chosen excerpt from The Magic Flute. In Autumn Sonata, Charlotte sketches the figure of Chopin before beginning to play Prelude. Bergman experiments with his sense of musical analysis throughout the entire film In the Presence of a Clown, which recounts Schubert's last days in both a free and erudite manner.

During the period heralded in with Through a Glass Darkly, music acquires a new dimension. It no longer strives to meld within the film in order to increase the drama, nor to build up the structure. Music is there for its own sake, detaching itself from the film and offers itself as an object to be listened to. Its presence is neither contextual nor structural, but rather metaphorical. However, what does the metaphor stand for? Why does the film suddenly give way to it? What is the meaning of this listening that Bergman invites us to?

The Silence, dominated by hatred and misunderstanding, allows for a moment of grace when the radio broadcasts the Goldberg Variations. Esther can then exchange a few words with the old groom, who also knows Bach.

One of the best scenes I have ever produced is the brief meeting in the darkness between the waiter and Esther, while Bach can be heard over the radio. He comes in, says the name Johann Sebastian Bach, and she says, ‘The music is beautiful’. It is a sudden moment of communication – so crisp.”

In the background, Johan is cuddling in his mother's arms. It is perhaps the first time the two sisters speak kindly to each other. Anna stands up and says that she is going out. After Esther turns off the radio, the nightmare resumes. However, for a brief moment, the music created a link between them. “We all live in our prisons, in our dreadful loneliness, surrounded by cruelty. The gift that music bequeaths us is to understand that there is a reality of infinite harmony beyond our earthly exile.”

A moment of comfort: Goldberg variation No. 25 on the radio.

© AB Svensk Filmindustri

“Prison”, “loneliness”, “cruelty”, “exile”. Each word seems to be applicable to The Silence. The break from this established by the Goldberg Variations in the middle of the film appears as a sudden truce in this world of suffering. Bach’s Partita, radio broadcasted in Shame, also provides Jan and Eva with a moment of peace, while war rages on outside.

In Hour of the Wolf, Bergman cites a short extract of The Magic Flute by using a puppet theatre. The performance takes place in the castle to which Johan and his wife have been invited. The audience surrounding them consists of demonic creatures. Here is how Bergman describes this scene: "The demons live the life of the doomed […]. For a moment, their suffering subsides: music offers them a few seconds of peace and solace.” He later explains:

In spite of the chaos that surrounds us, we must take care of the good things in life and protect them. I'm thinking of The Magic Flute, when the young prince, in the darkness, wonders if Pamina is still alive, and through which Mozart tells us, transmits to us something about spiritual reality. […] Each moment that wrests us from our loneliness – and you know it is total – is the best thing that can happen to us.

The passage cited in the film shows us Tamino at the moment when, lost and disheartened, he questions to the darkness whether Pamina is still alive. His situation echoes that of Johan, the main character in the film, an artist consumed by anxiety (Max von Sydow). And when the choir answers, “Pamina, Pamina lebet noch”, the camera shifts to his new wife (Liv Ullmann), a new Pamina. Hence, the piece by Mozart serves as a parenthesis in the overall structure of the film, a parenthesis shedding light on the narrative, arousing our interest rather than distracting us from it. It serves not as a digression, but rather as an explanation of what the characters are experiencing. Music becomes an active component and offers a psychological commentary on the scene, which doesn’t prevent it from serving as a respite in the midst of a very dark film.

One final example of music serving as a metaphor of communication between people is worthy of mentioning, this time from Cries and Whispers. In this film, the saraband of Bach’s Suite No. 5 features twice. The first time it accompanies a brief reconciliation between Maria and Karin. The cello turns into a voice, as if translating the inaudible words whispered by the two sisters. By analysing this scene bar by bar (on the soundtrack) and shot by shot (on screen), we understand that the first note is played at the very moment Karin kisses her sister, whom she previously rejected. Then, the first two shots fit the first two bars of the music score to a tee. Several distant shots shift from Karin to Maria and back in a dazzling choreography – the rhythm here is dictated by the music, as the motion is consistently triggered by the second or third beat of the bar. Bergman seems to connect the filming as much to the music as the music to the filming, so that the editing of this sequence is in itself musical.

The saraband features once again, when Anna lulls Agnes like a Pietà. Here too, music stands as a metaphor of the communication between people, communication which (as in The Silence) seems to suspend time and challenge death. The image remains unchanged for three bars, and the obsessive ticking of the clock, which has regularly appeared since the opening credits to remind us of the imminence of death, has stopped.

If music is a means of communication, is it not because it allows us to dispose of the spoken language? In Bergman’s work, words are often deceptive or offensive, at best incomprehensible, as in The Silence. “Words are used to conceal reality, aren't they? […] Music is a much more reliable means of communication,” says the director in an interview. Many illustrations of this concept can be spotted in his films.

In Persona, for example, Elisabeth wants to rid herself of the roleplaying and masks (translation of the Latin word ‘persona’). As language is “the most deceitful material of the mask”, where is this quotation taken from? she decides to remain silent. At the beginning of the film, as she is lying in a hospital bed, Bergman features a long sequence of Bach's Violin Concerto in E Major. On screen we witness a close-up of Elisabeth's face, staring into the camera and slowly fading into obscurity. It is as if Bach's concerto leads us step by step into her inner world. Music is a language which does not lie as it does not speak.

We find this mask/music dialectic again in Hour of the Wolf. Bach's Partita No. 3 is played on harpsichord by the demon Kreisler, as an equally demonic old lady literally removes her face to “better hear the music”. In a more figurative manner, Charlotte reveals herself in Autumn Sonata, when she plays a Prelude by Chopin. It is her own picture that she draws when she says she is in pain, but does not show it. At this moment she seems to be speaking truthfully, whereas previously she has always kept up appearances, as her daughter accuses her in the following nocturnal confrontation. We can concur with France Farago when she writes, “Music plays a privileged role in Bergman's work: the fulfilled hope of true communication, a song freed from all confines of language”.

The audience filmed by Bergman in the opening of The Magic Flute is composed of men and women of every age and race, addressing the universal goal of Mozart's opera. Music crosses all boundaries – even those of death, according to Eva in Autumn Sonata. Her son was killed when he was four years old. And yet, in his old nursery, still untouched, she tells her mother,

He lives in his own world, but we can reach one another at any time. There are no boundaries, no walls. […] There are no limits, neither in thought nor emotion. […] When playing the slow movement from Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata, surely you feel that you're living in a limitless world, the movement of which you will never be able to explore or penetrate.

This conviction is most strongly expressed in Saraband, Bergman’s final masterpiece. The suite previously heard in Cries and Whispers appears several times and is associated with Anna, Henrik's wife, who died two years previously, but whose loving presence radiates throughout the film. The character is most likely modelled after Ingrid von Rosen, Bergman's last wife, who died in 1995. In the fifth scene (central in all meanings of the word), Henrik confesses to Marianne that he imagines Anna is waiting for him somewhere.

All our lives we wonder about death, about what comes and doesn’t come next. It is so simple. Sometimes, through music, I glimpse an idea of it, like with Bach.

As he is speaking the saraband plays, creating a bridge between this world and the next. Bergman wrote in A Spiritual Matter, “I have always believed that music brings us earthly creatures closer to the unconceivable, to God.”

The filmmaker passed away on 30 July 2007. He hoped to meet his wife. Is this why he requested that the very same saraband be played at his funeral? Regardless, it resounds like an echo from his last film – art, more than ever, is reunited with life, even at death.

If music signifies a hope of communion, the lack of it signifies despair. In Shame, Jan's violin is shattered in an air raid. This loss introduces the second part of the film, in which Jan turns from a victim into a murderer.

Likewise, in Winter Light, we bitterly experience the absence of music – except for a few songs played during mass – as a sign of God’s silence and the loss of faith. As Michel Estève points out, “Some of the most beautiful shots in the film – close-ups of communicants, Christ's face and crucified hand, mid-shots of Karin and her children viewed by the pastor through a glass, Jonas's body wrapped in a tarp – are completely silent shots.” Bergman’s most desperate films, shot during his exile in Germany, feature no musical references. In From the Life of the Marionettes, Peter dismally discovers that “there is no way out”, while the hospital where Abel is working in The Serpent's Egg is an infernal labyrinth with no escape. The closing credits feature a silent, looming crowd. All sound has disappeared. The silence is absolute and eerie, as in the initial nightmare in Wild Strawberries, when Isaac encounters his own dead body. Likewise in The Seventh Seal, when Death arrives to take the knight away: the sound of the ebb and flow of the waves ceases and life stands still.

Music as a Source of Inspiration

Questioned about his relationship to music in an interview from 1982, Bergman asserts, “Music has always been […] one of the most important sources of inspiration for me, perhaps even the most important.” Even if no musical references appear in Winter Light, the film’s origin is nonetheless musical. According to Bergman, the film began with his discovery of Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms, which he heard on the radio, giving him the idea to shoot a film in an isolated church in the Swedish countryside.

Music not only gave birth to Winter Light, but also to The Silence, which Bergman claims was born out of Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra. “My original idea was to make a film that followed musical rules, instead of dramaturgical ones, a film that functioned through association – rhythmically, with themes and counter-themes. As I was putting it together, I thought much more in musical terms than I had done before. All that remains from Bartók is the very beginning. The film follows Bartók's music rather closely, with the dull continuous tone, then the sudden explosion.” The film begins in the muggy atmosphere of a train, where the passengers fall into torpor. The rhythm is slow and heavy. Then comes the “explosion” – a restless city, with its cacophony of car horns and people shouting. Hour of the Wolf, according to the filmmaker, is based on The Art of Fugue. As in Bach's work, with its open ending, Bergman's film stops in the middle of a sentence and remains unfinished (we'll never know what happens to Johan).

How does music inspire Bergman? “I don't know exactly, but sometimes a piece of music creates an emotional link, a situation. […] Music frees up something that wants to be expressed and told.” An emotional discharge sets the imaginary into motion. Käbi Laretei tells, for example, how Chopin's Mazurka in A Minor gave birth to the final scene in Cries and Whispers (where the Mazurka is featured). The title of the film can be linked to an expression used by the critic Yngve Flyckt, when speaking of the final movement in Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 14 in E-Major.

'If I had been given that gift and hadn't become what I am, I would most probably have become a conductor,' writes Bergman in The Fifth Act. Indeed, the filmmaker considers his work similar to that of a musical conductor, and he continuously resorts to musical metaphors. First and foremost, he enjoys comparing scripts to music scores. In the preface to Persona, he states, “I didn't write a film script in the usual sense of the word. What I wrote seems to me to be more like a music score that I will conduct during the filming.”

Page from the handwritten script of Persona. Dated Ornö 17 June 1965.

Photo: Jens Gustafsson © Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

Bergman expands upon this metaphor, “You write down a melodic line and after that you work out the instrumentation with the orchestra.” The actors are compared to valuable instruments. “You know, just as I have hugely enjoyed working with these actors, so does a violinist enjoy playing a Stradivarius.” The beat, dynamics, articulation and expression, rhythm and musicality – these words are frequently used during rehearsals. When asked about Bergman during the shooting of The Touch, Max von Sydow replies, “He gives you a rhythmic sketch of your role – the pauses, the increasing speed of the action, the point where the explosion comes, or where it should have come when it doesn’t. You think of musical similes.” Also, “I have witnessed him as a man who intrinsically feels the rhythm of the text, and very early on communicates this to the actors.” Once again, music is used as a model. “It is such a precise art, everything is in the score. We must try to work with as much precision, with silences and accentuations.” Therefore, Bergman claims to be very attentive to the precision of the voices and intonation used on the set. “Hearing is the most important sense of all. When studying a scene, I often close my eyes and listen. If it sounds right, it looks right.” He further extrapolates, “Your hearing is always more sensitive and in tune with your feelings than your sight.” This method caused confusion on the set of Autumn Sonata, with Ingrid Bergman blaming the filmmaker for not looking at her during the filming.

Ingrid Bergman (Charlotte) and Eva (Liv Ullmann) instructed by the director.

Foto: Arne Carlsson © AB Svensk Filmindustri

But the director viewed his role differently, with his relationship to the actors being above all a matter of listening. When asked about how he directed his highly admired actors, Bergman replied, “There is nothing more mysterious about it than their trust in my hearing and my trust in their perceptiveness.” Liv Ullmann describes him as a great listener… The film editing stage is described as “the vital third dimension, without which the film is merely a dead product from a factory”. According to Bergman, this stage provides the film with its very breath. “I learned that from a conductor. […] He said, ‘Ingmar, music is breathing.’” Cinema has much to learn from the pulse of music and its rhythmic dimension.” Everything is rhythm, more so in film than in anything else.”

'As a creator of films, I have learned an enormous amount from my devotion to music,' confesses Bergman. Music serves not only as a source of inspiration for him during the writing process, but is also a tool during the filming and editing. Thus it comes as no surprise that his films resemble musical compositions, even when they fail to feature any musical works.

Åke Grönberg and Annika Tretow in Sawdust and Tinsel.

Photo: Hans Dittmer © Sandrew Metronome

Such is the case in Sawdust and Tinsel. “To use musical terminology, the main theme is the episode with Frost and Alma. Then, within a uniform time period, a number of variations take place – both erotic and humiliating in ever-changing combinations.” These ‘variations’ include the visit to the theatre, the reunion between Albert and his wife, and his final humiliation in the fight with Franz… A few years later, in The Devil’s Eye, the musical metaphor defines the true nature of the film. The film by-line itself is, “A rondo capriccioso with Ingmar Bergman”. Autumn Sonata is also composed as a musical piece.

When I began making notes for Autumn Sonata, the film was a dream about a mother and daughter shown at three different times of the day – morning, noon and night. That was the entire idea. Just the two of them shot at those times, no explanation, no story. Three movements, as in a sonata.

Indeed this film is made in three movements: the first is slow and peaceful (Charlotte's arrival); the second, violent and passionate (the nocturnal showdown); the third one, calm and sad (Charlotte's departure). Just as in a sonata, two themes can be detected – the mother's and daughter's. In another light, the influence of music inspired what Bergman refers to as his “chamber films”: Through a Glass Darkly in 1961, then Winter Light, The Silence, Persona… He took the idea from Strindberg’s Intimate Theatre, which is modelled on Max Reinhardt’s Kammerspielhaus. With chamber music as a guide, Bergman’s goal was to rediscover the essence of theatre, by limiting the number of actors and simplifying the sets. In Through a Glass Darkly, there are only four characters: Karin, her brother Minos, her father, and her husband – a quartet. Michel Chion's remarks on the film are worth citing.

The action begins as a strong chorus of instruments, which later pair off. […] Bergman uses this separation to rapidly switch, through alternate editing, from one duet to the other, in order to highlight differences in rhythm and tonality. The two young people walk and speak with vivacity, whereas the two adults struggle to row a boat. They then all gather outside to share a meal, which begins with an animated feeling but later is imbued with an awkward silence. The father, attacked by guilt over his numerous absences and self-centredness, escapes into the house and weeps. When he returns outside, the other three welcome him rambunctiously, leading him around the grounds, speaking on top of one another. […] From the offset, character combinations alternate endlessly, as does the rhythm and tonality.

Bergman always considered his films to be pieces of music. Speaking about Persona, he says, “I thought about the happiness of musicians, for whom life is so easy – they write Opus 14, Sonata No. 9, and it says exactly what it intends to say. That was my intention – entitle my film Cinematography No. 27.” How else could we interpret the title of his final “opus”, Saraband? The saraband from Bach's Cello Suite No. 5 features numerous times in the film. But the reference runs deeper still. “A saraband is actually a partner dance, described as being very erotic and was even banned in 16th-century Spain.” He adds, “The film follows the structure of the saraband, with two people meeting.” The first scene brings Johan and Marianne together, the second unites Marianne and Karin, while the third poses Karin against Henrik. The fourth scene is a confrontation between Henrik and Johan, and the film goes full circle. This chain of events is reminiscent of a dance and allows Bergman to introduce the characters in succession. The title of this filmic legacy is also a way to draw attention to the many sarabands Bergman used throughout his work: Suite No. 2, featured in both Through a Glass Darkly and All These Women, Suite No. 4, featured in Autumn Sonata, and Suite No. 5, featured in Cries and Whispers. Saraband refers to all of these. Likewise, the saraband from Partita appears in Hour of the Wolf, Shame and A Passion.

Julia Dufvenius and Börje Ahlstedt in Saraband.

Photo: Bengt Wanselius © SVT Bild

Furthermore, the reason behind why the movie seems like a saraband may be that, for Bergman, “film and music are nearly the same. They are both means of expression and communication which bypass reason and reach our emotional centres.” Is not this common capacity of music and cinema to bypass reason that which allows them to express the unspeakable? At the end of Saraband, Marianne pays a visit to her daughter Martha, who is ill. Bach can be heard at the very moment when Martha, who until then had her eyes closed to the world, opens them to look at her mother. In this scene, Bergman achieves what he himself defines as the common goal of music and cinema. “When you hear one of the last symphonies by Mozart, […] suddenly the roof opens up on something bigger than the limitations of the human being. […] Filmmaking is an attempt to open that roof, so that we can breathe.”

If film and music are the same thing, “the term ‘film music’ is really absurd,” says Bergman. “It comes down to common sense – you can't accompany music with music. So you must place the music within the film as a new dimension.” This statement from 1964 indicates how Bergman's relationship to music evolved – from Crisis to Saraband. Music featured in his early films functions as a pleonasm, serving to intensify emotionally-charged scenes, as does original film music. In Through a Glass Darkly and The Silence, however, the music requires closer listening, as it brings its true meaning to the film, a new element that the film allows it to express – the fulfilled hope of real communication. From that point on, Bergman's musical choices become more personal. The figure of Chopin reflected in Music in Darkness by the romantic Nocturne is the most conventional. A few decades later, the Prelude played successively by Eva and her mother in Autumn Sonata is neither “pleasant” nor well-known. However, the stern, repetitive melody expresses true suffering with an exceptional harmonic audacity. Bergman refers to music as his most important source of inspiration. He commonly wrote scripts as composers write scores, directed the actors as conductors lead their orchestras, and entitled his films “Sonatas” and “Sarabandes”… This device also encompassed his personal life, and Bergman most likely used music as Tamino his flute – to tame his demons.

Translation: Jon Asp, Sarah Snavely.

Sources

- Assayas, Olivier and Björkman, Stig, Conversation avec Bergman (Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma, 1990).

- Aumont, Jacques, Ingmar Bergman, “Mes films sont l'explication de mes images” (Paris: Cahiers du cinéma, 2003).

- Bergman, Ingmar, Four screenplays (1960) (New York: Sixth paperback printing, 1969).

- Bergman, Ingmar, Images: My Life in Film (New York: Arcade Publishing, 1994).

- Bergman, Ingmar, The Fifth Act (New York: The New Press, 2001).

- Bergman, Ingmar, New Swedish Plays (Norwich: Norvik Press, 1992).

- Björkman, Stig, Manns, Torsten and Sima, Jonas, Le cinéma selon Bergman (Paris: Seghers, 1973).

- Chion, Michel, La Musique au cinéma (Paris: Fayard, 1995).

- Cowie, Peter, Ingmar Bergman: A Critical Biography (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1982).

- Jones, G. W., Talking with Ingmar Bergman (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1983).

- Koskinen, Maaret ed., Ingmar Bergman Revisited (London: Wallflower Press, 2008).

- Laretei, Käbi, Såsom i en översättning (Stockholm: Bonniers, 2004).

- Long, Robert E. ed., Liv Ullmann Interviews (University Press of Mississippi/Jackson, 2006).

- Marker, Lise-Lone, “A Conversation with Ingmar Bergman”, in Ingmar Bergman: A Life in the Theater (Cambridge University Press, 1982 (re-edited in 1992)).

- Samuels, Charles T., “Encounter with Ingmar Bergman”, in Ingmar Bergman: Essays in Criticism, Stuart M. Kaminsky ed. (Oxford University Press, 1975).

- Shargel, Raphael ed., Ingmar Bergman Interviews (University Press of Mississippi/Jackson, 2007).

- Simon, John, “Conversation with Bergman”, in Ingmar Bergman Directs (New York: Harcourt, 1972).

- Steene, Birgitta, “An Interview with Ingmar Bergman”, in Focus on The Seventh Seal (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1972).

- Wirmark, Margareta, “Regissör Ingmar Bergman och hans skådespelare”, in Ingmar Bergman Film och Teater i växelverkan (Stockholm: Carlssons, 1996).

Bergman's musical quotations

Prison

Bach, Cantata No 137 (1725) – Church bells, repeated twice

Thirst

Mozart, Non più andrai, from The Wedding of Figaro (1786) – Whistled by Raoul

Music in Darkness

Händel, Ombra mai fù (Largo), from Serse (1738) – Organ/Bengt

Beethoven, Moon Light Sonata, Opus 27 No 2 (1801) – Piano/Bengt

Schumann, Fantasiestück No 2: ”Aufschwung”, Opus 12 (1837) – Piano/Bengt

Chopin, Ballad No 3 in A flat minor, Opus 47 (1840-41) – Piano/Bengt

Chopin, Vals No 7 in C sharp minor, Opus 64 No 2 (1846-1847) – Piano/Bengt

Chopin, Preludium i D-dur, Opus 28 No 24 (1836-38) – Piano/Bengt

Beethoven, Symphony No 3 in E major, Opus 55, "Eroica", finale (1804) – Grammophone

Chopin, Nocturne in E flat major, Opus 9 No 2 (1831) – Piano/ Bengt

Wagner, ”Treulich geführt, ziehet dahin” (Bridal march), from Lohengrin (1850) – Violin

To Joy

Beethoven, Symphony No 9 in D minor, Opus 125, "To Joy" (1824) – Orchestra rehearsal, prologue and epilogue

Beethoven, Egmont, Ouverture, Opus 84 (1810) – Orchestra rehearsal

Smetana, La Fiancée vendue, Ouverture (1866) – Orchestra rehearsal

Mozart, Quartet for Flute, Violin, Viola and Violoncell in A major, KV 298 (1778) – Twice: Stig and Marta's quartet, later off-screen

Mendelssohn, Violin concerto in E minor, Opus 64 (1844) – Twice: Stig's solo and orchestra rehearsal

Beethoven, Symphony No 1 in C major, Opus 21, fourth movement (1800) – Orchestra rehearsal

Summer Interlude

Bach, Cantata No 137 (1725) – Church bells in the prologue

Tchaikovsky, Swan Lake, Opus 20 (1877) – Royal Opera, four times

Tchaikovsky, Nut Cracker (1892) – Grammophone

Chopin, Impromptu No 4 in C flat minor "Fantaisie-Impromptu", op. postum (1834) – Piano/Erland

Chopin, Etudes in C minor, Opus 10 No 12 (1832) – Piano/Erland

Waiting Women

Gluck, "Dance of the Blessed Spirits" from Orpheus and Euridice, Act 2, scene 2 (1762) – Off-screen

Summer with Monika

Johann Strauss, fils, An der schönen blauen Donau, Opus 314 (1867) – Grammophone

Johann Strauss, fils, Wiener Blut, opus 354 (1871) – Grammophone

A Lesson in Love

Wagner, ”Treulich geführt, ziehet dahin” (Bridal March), from Lohengrin (1850) – Off-screen

Johann Strauss, fils, An der schönen blauen Donau, Opus 314 (1867) – Chamber orchestra

Smiles of a Summer Night

Schumann, Fantasiestück No 2: "Aufschwung", Opus 12 (1837) – Piano/Henrik)

Liszt, Liebestraum, Opus 62 No 3 (1850) – Piano/Henrik

Mozart, La ci darem la mano, from Don Giovanni, Act 1, scene 9 No 7 (1787) – Hummed by Fredrik

Chopin, Impromptu No 4 in C flat minor "Fantaisie-Impromptu", Op. posthumous (1834) – Piano/Henrik

Wild Strawberries

Bach, Das wohltemperierte Klavier, Fugue No 8 in E flat minor, BWV 853 (1722) – Piano/cousin Sara

The Seventh Seal

Dies iræ, dies illa ("Day of Wrath") Lyrics: Thomas of Celano (Latin) in Swedish translation by Severin Cavallin, 1882. Swedish arrangement: Johan Bergman, 1920. [Not on Spotify.]

The Devil's Eye

Scarlatti, Sonata in E major, K 380 – Piano/Käbi Laretei once; off-screen twice

Scarlatti, Sonata in D major, K 535 – Twice off-screen; Instrumentalist: Käbi Laretei

Scarlatti, Sonata in F major, K 446 – Five times off-screen; Instrumentalist: Käbi Laretei

Through a Glass Darkly

Bach, Cello suite No 2 in D minor, IV. Sarabande (1721) – Four times off-screen; Instrumentalist: Erling Bløndal Bengtsson

The Silence

Bach, Goldberg variation No 25 (1742) – Radio

All These Women

Bach, Orchestral Suite No 3 in D major, BWV 1068, Air (1722) – Cello/Felix, three times; grammophone, twice; cello/Giovano, once

Bach, Cello suite No 2 in D minor, IV. Sarabande (1721) – Cello/Felix

Beethoven, Adelaide, Opus 46 (1795) – Sung by Cornelius twice

Offenbach, La Belle Hélène (1864) – Instrumental

Massenet, Thaïs, Meditation (1894) – Instrumental

Persona

Bach, Violin concerto in E major, BWV 1042, Adagio (c. 1720) – Radio

Hour of the Wolf

Mozart, The Magic Flute, Act 1, scene 15 No 8, Finale (1791) – A puppet theatre

Bach, Partita No 3 in A minor, BWV 827, Sarabande (1726-1731) – Harpsichord/Kreisler

Shame

Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No 4 in G major, Andante, BWV 1049 (1721) – Hummed by Jan

Bach, Partita No 3 in A minor, BWV 827, Sarabande (1726-1731) – Radio

A Passion

Bach, Partita No 3 in A minor, BWV 827, Sarabande (1726-1731) – Elis' studio

Cries and Whispers

Bach, Cello suite No 5 in C minor, Sarabande (1724) – Off-screen twice; Instrumentalist: Pierre Fournier

Chopin, Mazurka in A minor, Opus 17 No 4 (1833) – Off-screen twice; Instrumentalist: Käbi Laretei

Face to Face

Mozart, Fantasie in C minor, KV 475 (1785) – A concert; Instrumentalist: Käbi Laretei

The Dance of the Damned Women

Monteverdi, Madrigal, book 8: "Il ballo delle ingrate", SV167 – Soprano: Dorothy Dorow

Autumn Sonata

Händel, Sonata in F major, HWV 369, Opus 1, IV. Allegro (1725-1726) – Credit sequence; Instrumentalists: Frans Brüggen, Gustav Leonhardt, Anner Bylsma

Chopin, Prelude No 2 in A minor, Opus 28 (1838-1839) – Piano/Eva, later Charlotte; Instrumentalist: Käbi Laretei

Bach, Cello suite No 4 in E flat minor, Sarabande (1723) – Cello/Leonardo; Instrumentalist: Claude Génetay

Fanny and Alexander

Schumann, Piano quintet in E flat major, Opus 44, II. In modo d'una marcia (1842) – Off-screen four times; Instrumentalists: Marianne Jacobs (piano) and Freskkvartetten

Vivaldi, Concerto for two mandolins in G major, RV 532, Andante (1740) – A bell

Verdi, Marcia trinonfale, from Aïda, Act 2, scene 2 (1871) – A brass band; Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Dvořák, Humoresque, Opus 101 No 7 (1894) – A beggar playing the violin

Schubert, Themes with variations in B major, Impromptu No 3, Opus 142 D 935 (1827) – Piano/Aunt Anna; Instrumentalist: Käbi Laretei

Beethoven, Bagatelles, Opus 33 No 4, Andante (1802) – Piano/Aunt Anna; Instrumentalist: Käbi Laretei

Schumann, Frauenliebe und -leben, Opus 42: "Du Ring an meinem Finger" (1840) – Sung by Lydia, Carl's wife

Chopin, Nocturne in C flat minor, Opus 27 (1834–35) – Piano/Aunt Anna

Britten, Cello suite No 2, Opus 80 (1967) – Off-screen; Instrumentalist: Frans Helmerson

Chopin, Sonata No 2, Opus 35, third movement, “Marche funèbre” (1837-1839) – A brass band; Stockholm Regionmusikkår (Per Lyng)

Schumann, Symphony No 4 in D minor, Opus 120, Romanze (1841, rev. 1851) – A quintet; Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Johann Strauss, fils, An der schönen blauen Donau, Opus 314 (1867) – Music box

Bach, Sonata No 2 for flute and harpsichord in E flat major, BWV 1031, Siciliana (1730) – Vergérus, twice; off-screen once; Instrumentalist: Gunilla von Bahr (flute)

Britten, Cello suite No 3, Opus 87 (1971) – Off-screen four times; Instrumentalist: Frans Helmerson

Jacques Offenbach, La Belle Hélène, Act II (1864) – A quintet; Arrangement: Daniel Bell

In the Presence of a Clown

Schubert, Winterreise, last song: "Der Leiermann" (1827) – Piano/Pauline once; grammophone twice; off-screen four times

Schubert, Symphony No 8, I. Allegro moderato (1822) – Piano/Pauline

Schubert, Walzer, Opus 18 D 145 (1815-1821) – Piano/Pauline

Schubert, Symphony No 9, III. Scherzo (1825) – Piano/Carl och Vogler

Schubert, Sonata in B major, D 960, II. Andante sostenuto (1828) – Piano/ Pauline, four times; Instrumentalists: Käbi Laretei and Hanns Rodell

Saraband

Bach, Cello suite No 5 in C minor, IV. Sarabande (1724) – Cello/Karin once; off-screen seven times; Instrumentalist: Torleif Thedéen

Brahms, String quartet No 1 in C minor, Opus 51, Romanze (1873) – Radio

Bach, Trio Sonata No 1 in E flat minor, BWV 525, I. Allegro moderato (c. 1727) – Organ/Henrik; Instrumentalist: Torvald Torén

Bruckner, Symphony No 9 in D minor, II. Scherzo (1887–1896) – Grammophone; Conductor: Herbert Blomstedt

Bach, Choral BWV 1117: "Alle Menschen müssen sterben" (1708) – Instrumentalist: Hans Fagius