Scenes from a Marriage

Television miniseries about the breakdown of a marriage that sent Sweden's divorce rate soaring.

"It took two and a half months to write these scenes; it took a whole adult life to live."Ingmar Bergman

About the film

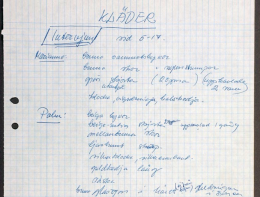

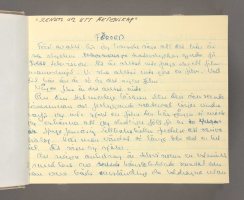

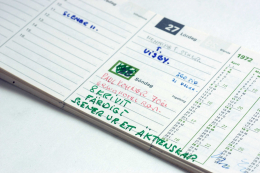

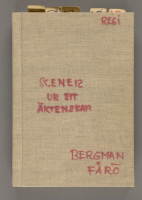

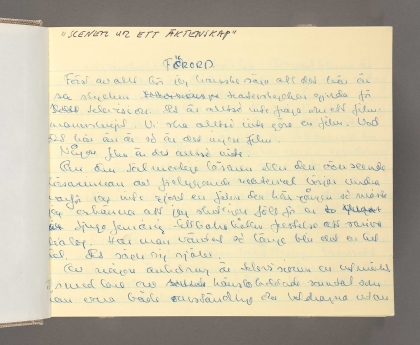

On 27 March 1972 Ingmar Bergman wrote in his workbook:

'Here's something we can do for the fun of it. It mustn't cost too much, nor involve any financial risks. We'll have lots of material to work with, as much as possible, I hope there will be an enormous amount. There'll be plenty of exciting dialogue to get stuck into. Nothing at all out of the ordinary. I rather fancy a series of scenes from a marriage.'

On 4 May 1972 the Swedish broadsheet daily Dagens Nyheter announced that, for the first time in his career, Ingmar Bergman was to write and direct a television series. "Thematically", Bergman explained, 'the series will be a follow-on from or an adaptation of the two middle class tragicomedies I have made for the cinema and television, The Touch and The Lie. Like those, "Scenes from a Marriage' (the working title of the proposed series), would deal with: 'the absolute fact that the bourgeois ideal of security corrupts people's emotional lives, undermines them, frightens them'.

'Why television?', Bergman was asked:

'When you live on Fårö you become an avid television viewer. Television is quite simply the most amazing thing. It opens up the whole world. I watch the weather forecast every evening, the news, too. And I really enjoy the music and dance programmes – not to mention the ice hockey! When the world championships were on a few weeks ago, I certainly didn't get much writing done on 'Scenes from a Marriage'.'

The transition to television was to be almost absolute. Virtually all of Bergman's films since Scenes from a Marriage have been made for television, whether series (Face to Face, Fanny and Alexander) or one-offs (The Magic Flute, Saraband). Admittedly, and for various reasons, they have all gone on cinema release, but they were intended for television. As Sven Nykvist has noted: 'What Bergman has made for television are not simply films on television, they are television films.' Bergman himself described Scenes from a Marriage as 'an aesthetically superior everyday product for TV'.

By 27 May 1972, Bergman had finished the screenplay. The original took the same six-part format as the finished series: 'Innocence and Panic', 'The Art of Sweeping Things Under the Carpet', 'Paula', 'The Valley of Tears', 'The Illiterates' and 'In the Middle of the Night in a Dark House Somewhere in the World'.

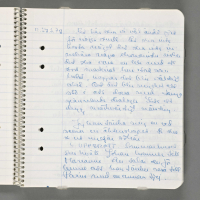

Bergman writing in Images:

Johan and Marianne became very real, very quarrelsome even. They had a good deal on their minds, and this form (straightforward dialogue without cinematographic complications) gave them natural occasions to speak out. I also discovered something else: that I was somewhat at odds with Johan and Marianne on many points. Yet despite this I realised that they should be allowed to speak out, just so long as I had the chance, at the end of the sixth episode, to say something that was very important to me personally.

Before I had time to reflect, there were six distinct dialogues about love, marriage and all manner of things besides. Johan and Marianne, or Marianne and Johan, had allowed themselves to be brave, cowardly, happy, sad, angry, loving, confused, uncertain, satisfied, cunning, unpleasant, childish, mean, unfathomable, magnificent, petty, physically affectionate, heartless, stupid, wretched, helpless: in a nutshell typical human beings.

The budget was tight, to say the least. Bergman's own company Cinematograph was now the sole producer, and since his previous film Cries and Whispers had not yet been sold abroad, cash flow in the organisation was poor. A cheaply-produced television series that could be sold at a good price was deemed to be the solution. Whereas the previous film had cost SEK 1.8 million, the entire TV series was budgeted at a relatively modest SEK 1.2 million, of which Sveriges Television would come up with half. Given the likely interest from overseas, the series was expected, at least, to break even. As with Cries and Whispers Bergman offered his actors the chance to invest their fees back into the film. Erland Josephson and Sven Nykvist took him up on the offer, while Liv Ullmann declined yet another gamble. (She should not have been so cautious, as we shall see!)

Despite, or because of, the lack of external funding, Cinematograph itself invested heavily. Bergman had long been toying with the idea that his company should be self-sufficient on the technical front. Accordingly, they set to work on the construction of a film studio on the estate in the 17th century village of Dämba on Fårö that Bergman had recently acquired and moved to. The studio was a mere 6 x 12 metres and housed in an old barn together alongside a props store. The office was in the old brewery, the coach house became the cinema, and the woodshed was transformed into an editing room.

Sources of inspiration

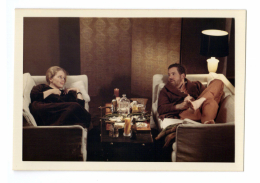

Scenes from a Marriage originates from the image of a successful and happily married couple sitting on a green velvet sofa being photographed for a magazine feature. This image provides the opening scene of the series. Bergman claimed to have met those people before. He had been friends with a Danish couple who were always pleasant, bountiful, and who never got drunk, just charmingly tipsy. They always said the right things, and even when they had the flu they still managed to be chirpy.

'I remember they irritated me so intensely, that I once tried to seduce the wife (this is over twenty years ago). I failed, of course, and that made me even more annoyed. I did it in pure desperation just to bloody well show them. Suddenly I pictured them sitting in my old sofa and being interviewed. And I thought: 'now I'll get them'

Many people regarded Scenes from a Marriage as a new departure in Bergman's work. No God, no Bergmanesque introspection, just a television series about 'people like you and me', as one journalist put it. Bergman concurred, recognising that it was the first time 'to his surprise' that he had written something about people outside his own life: 'I've used my own and other people's experiences. But I haven't projected myself and my own life into this.'

Yet when he was asked why it was that Scenes from a Marriage was so different from the Bergman films that people were used to, he replied: 'Well, you know, you're getting the same old bastard really. These are just some other things that have been there all the time, but have only just come up to the surface.' Bergman's interviewer continued along the same lines, light-heartedly questioning the non-appearance of God, neither in conversation, nor even disguised as a waiter or a gardener. 'You're absolutely right that God doesn't feature,' he replied. 'But I'm far from a non-believer. I'm a believer in the truest sense. I believe in the sanctity of man.'

As cited above, Bergman himself did not feel any close affinity with Johan and Marianne, even though he did admit they shared some characteristics in common:

'[...] such as our middle class background, with its double-edged impact on character development (that sounded good, didn't it?). Both of them are academics, something which shouldn't be a burden to them, and they're well-off to the extent that they live in a house and each have their own cars and jobs. They're also used to putting their thoughts into words, which doesn't mean that they say the right things or that they are more honest or sagacious than other people in general.'

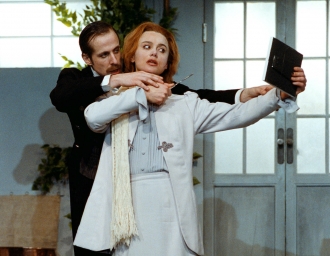

In the first episode Johan and Marianne have invited their friends Peter (Jan Malmsjö) and Katarina (Bibi Andersson) round for dinner. In Images: My Life in Film Bergman says of this couple: 'Peter och Katarina cannot live with each other or apart. They commit cruel acts of sabotage against each other, actions that only two individuals this close could invent. Their time together is a sophisticated and destructive dance of death.' The words 'Dance of Death' are particularly apt, since the shadow of August Strindberg can definitely be discerned in this picture of marriage as hell on earth. The couple have also been compared to George and Martha in Edward Albee's classic Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which Bergman had staged at the Royal Dramatic Theatre Dramaten in 1963.

Bergman has said that Scenes from a Marriage took 'took a whole adult life to live'. At least one part of that life has a direct parallel in the series. In his autobiography The Magic Lantern Bergman recounts how he ran away from his wife to Paris with Gun Hagberg. He told his wife 'everything', he says, adding that: 'Anyone interested can follow the events in the third part of Scenes from a Marriage. The only difference is the depiction of Paula, the lover. Gun was more like her opposite.'

Shooting the film

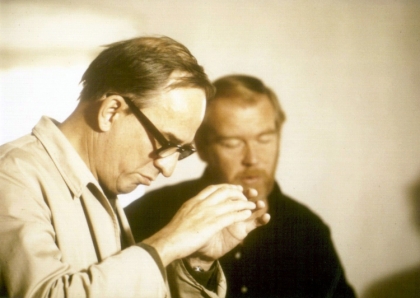

Shooting began on 24 July 1972 and took place, with the exception of a few outdoor shots, entirely on Fårö. Since Bergman had moved there he had become involved in this isolated island and its population problems, mostly caused by people moving away. (He explored this theme in Fårö Document and Fårö Document 1979). With its new film centre, Cinematograph was able to operate a kind of regional policy of its own, in which as many of the crew as possible could be recruited locally. One of them was Arne Carlsson. At 23 he landed his first job for Bergman as a driver during the filming of The Hour of the Wolf, following which he was an odd-job man, props assistant, assistant studio manager and assistant director. Later, he was to become a stills photographer, sound technician and director of photography. But his job on this occasion was boom operator. Other local talents included the grip and joiner Bo Erik Olsson, who owned 'the fanciest car on the streets of Dämba', Adolf Karlström, the architect and builder behind the renovations on the estate, and his wife Siri who cooked for them all.

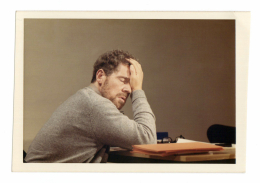

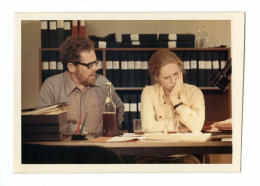

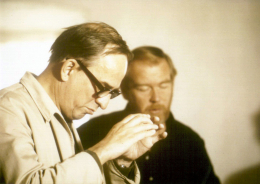

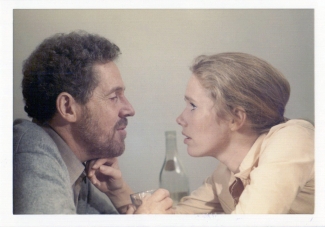

In the more prominent roles, the team was a familiar one: Liv Ullmann played Marianne and Erland Josephson was Johan. As usual, Sven Nykvist was behind the camera. All of them lived on Fårö for the entire shoot. Since Dämba Mill had not yet been converted to residential accommodation, they stayed at a holiday village a few kilometres away. Josephson compared the experience to being on military service and Nykvist described it as a 'marriage with divorce built in'. Ullmann appears to have been particularly taken by of the non-flush outside toilets on the site: 'It's windy, the sea is roaring and it's dark. There you sit enthroned, experiencing all the majesty of the wind and waves.'

But the filming was not entirely tension free. Bergman and Ullmann had recently ended their relationship, and Bergman was already remarried. Even though they remained friends, relations between them at this time were still somewhat strained. Nykvist recalls an incident at the start of filming:

Erland, Liv and I were sitting in a caravan, when Liv suddenly said:

'There go my boots!'It was Ingrid, Ingmar's new wife, who had put on a pair of boots that Liv must have left in the house after the split.

Jealousy flared up, provoked, as is so often the case, by an absurd detail. Feeling hurt, Liv ran out and hid in a large wooden packing case with a lid that was standing in the studio. She refused to come out.

Scenes from a Marriage was shot in 16 mm, partly for reasons of costs, and partly since the TV screen does not require a higher resolution. Moreover, the studio was cramped, and lighter equipment made for better manoeuvrability. Filming proceeded at a hectic pace. Cries and Whispers had been filmed in forty-two days, an amazing achievement in itself. As a producer Bergman appears to have been considerably more 'demonic' than as a director, since he was now counting on a shoot of similar length for a production with a running time three times as long – five hours in all. This equated to roughly one episode per week.

Amazingly enough, they managed to finish before schedule. Compared to Bergman's usual rate for a feature film of three minutes of footage for one day of shooting, here they managed as much as twenty minutes. One obvious reason for this was the sheer commitment of the actors. Josephson and Ullmann made a sport of producing their part of the work as quickly and efficiently as possible. They got up at five every morning to ensure maximum preparation for the first takes of the day. Furthermore, they were clearly wrapped up in the characters they played. As Bergman has said: 'Their efforts were invaluable, because they never gave up on Marianne and Johan, they stuck up for them. As a result, many of Liv's and Erland's suggestions for their lines and some of the scenes were absolutely central to the end result.'

Epilogue

Shooting came to an end on 3 October 1972, and the six-part series was first shown in on Sweden's TV2 in 1973. The response was enormous. The penultimate episode, which drew the biggest viewing audience, was seen by 3.5 million Swedes, virtually half the population. Bergman was clearly delighted, unquestionably not just for financial reasons as the producer, but because he was reaching out to so many people at once: 'If only a few people sit down in the kitchen and talk about it afterwards over a beer and sandwich, then I'm pleased.'

And talk they did. The divorce rate in Sweden is widely reputed to have shot up after the series. And Bergman was forced to go ex-directory (a rarity in Sweden, especially at that time) to avoid telephone calls from strangers wanting to discuss their marriage with him. 'I couldn't just turn into one of those public service bureaus...' He was referring to the marriage guidance service, which saw a huge increase in its number of clients. Reports confirm that the waiting list to the marriage guidance services in Stockholm went up from three weeks to three months. 'At our three offices in Stockholm we have 19 counsellors. That's not nearly enough,' said social welfare officer Barbro Marmell.

The newspapers responded to the series with a record number of articles. One typicaL headline in a popular television and radio guide ran: 'We watched Bergman's 'Scenes from a Marriage' together with a younger married couple: But really it's about us!'

The tabloids were full of questionnaires in which people of all ages, married or unmarried, could express their views on the series, not least its ambiguous ending. To coincide with the last episode, Aftonbladet urged its readers to write in and say whether Johan and Marianne should stay divorced, or whether they should try for a reconciliation. Views were split down the middle. Widow Lilly Wigholm, 68, thought they should stay divorced since they had both been unfaithful and had come to blows. A 14 year-old schoolgirl, Barbro Gustavsson, though that they should stay together because they were so well suited. The most original suggestion came from mechanic Bert Svensson, 28: 'Johan should go back to his lover, and Marianne to hers. Then they can all indulge in group sex.'

Aftonbladet's television critic Hemming Sten was concerned that such a meaningful yet provocative television series had been broadcast without any guidance or follow-ups: 'People should have some assistance to understand the characters and their actions. An interview with Bergman afterwards, a discussion among experts, perhaps a phone-in service.' By way of conclusion, Sten hoped for something of this nature when the series was repeated, perhaps in the form of organised evening classes. (Evening classes were enormously popular in Sweden during the 1970s).

Following such phenomenal success in Sweden, international interest was aroused. The series was successfully sold and broadcast as a television series in a number of countries. Subtitles, however, presented a problem: there was a lot of dialogue and only a limited space on the TV screen. In some countries it was dubbed, but the results were far from satisfactory. Distributors in the US were keen on a cinema version, abridged and transferred onto 35mm film. To begin with, Nykvist refused: 'We'd shot the series in the 16 mm format 1: 1.33. Now it was to be blown up to 1: 1.66. I looked at some samples. The cropping was extremely ugly, and the images were grainy. I called Ingmar and told him that we couldn't agree to this.' Nykvist cited the fact that the subtitles would obscure the actors' mouths, and that his contract stipulated that it would only be screened in 16 mm.

Bergman, always more pragmatic than his reputation might suggest, replied: 'Have you forgotten that you're a co-producer? We're not talking small change here. You've got ten per cent of the rights.' The television series was duly abridged from 278 to 155 minutes and shown at cinemas (a similar fate would subsequently befall Fanny and Alexander). Bergman remained unsentimental about shortening the film: The only sequences he felt any twinges about cutting were the credits, which in the original version comprised a landscape over-dubbed with Bergman's own voice: 'While you're looking at Sven Nykvist's beautiful picture of Fårö...' followed by a list of the cast and crew. The Americans thought this was utterly unfathomable.

Expressen's description of the arrangement made it seem as if the Americans had sequestered the Holy Grail: 'The American distributor Donald Rugoff has recently been in Stockholm to collect his copy in person. He flew home with the reels yesterday. Rugoff was in raptures. He had a golden calf in his suitcase. After the enormous success of 'Cries and Whispers' in the US, 'Scenes' is tipped as a box-office cert.'

Seen by more viewers perhaps than any other of Bergman's works, Scenes from a Marriage has influenced and inspired countless people, not only in terms of changing their lives, but also in an artistic sense. This, however, is rather dubious, in some cases: David Jacobs, the creator of Dallas, has said that he had originally conceived an American version of Scenes from a Marriage. It was only when the bosses at CBS entreated him to 'try something rich' that Johan and Marianne's American counterparts ended up in the oil business. Woody Allen's Husbands and Wives, perhaps, displays more direct affinities.

Scenes from a Marriage is in many ways unique among Bergman's works. It is also his only film to have been adapted for the stage: Bergman himself produced it at the Theater im Marstall in Munich in 1981 as Szenen einer Ehe, and it has also been staged by directors at numerous theatres around the world. Its straightforward cinematic style probably facilitated its transformation to a stage play: even at the planning stage Bergman envisaged Scenes from a Marriage as a series of dialogues, 'nothing at all out of the ordinary.'

Certain characters from Scenes from a Marriage were to reappear later in Bergman's work. The protagonists in From the Life of the Marionettes are the same Peter and Katarina who appear in the first episode. Their relationship has by no means improved. And in what Bergman has said will be his last television film, Saraband, Johan and Marianne appear once again. The film was promoted as a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage, yet although two of the principal characters bear the same names, they share very little else in common with their precursors. During the media frenzy that followed the first broadcast of the television series, Bergman was asked time and time again whether he would make a sequel. 'Never', he replied.

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives.

- Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film.

- Ingmar Bergman, The Magic Lantern.

- Peter Cowie, Ingmar Bergman: a critical biography, (London: Secker & Warburg, 1982).

- Frank Gado, The Passion of Ingmar Bergman, (Durham, N.C.: Duke Univ. Press, 1986).

- Sven Nykvist, Vördnad för ljuset: om film och människor, red. Bengt Forslund, (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1997).

- Röster i Radio TV, no 15, 1973.

- Röster i Radio TV, no 39, 1974.

- "Bergman bygger filmstad på Fårö, skildrar äktenskap i Djursholm", Dagens Nyheter, 30 August 1972.

- "Jag tror på det heliga i människan", Veckojournalen, no 15, 1973.

- "Köer till familjebyråer efter deras TV-gräl", Expressen, 27 May 1973.

- "Hela världen får se halva 'äktenskapet' ", Expressen, 27 August 1974.

- "En uppenbarelse för många människor", Aftonbladet, 17 May 1973.

- "Bergmans TV-serie förlaga till 'Dallas'", Aftonbladet, 3 July 1986.

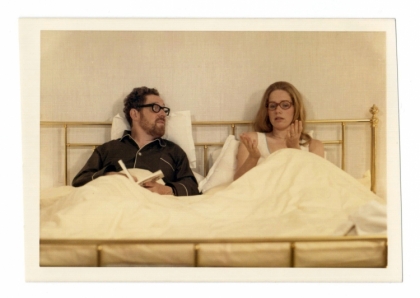

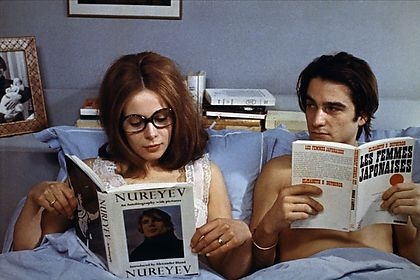

Bergman once admitted: “I did like Truffaut enormously, I esteemed him, in fact. His way of relating with an audience, of telling a story, is both fascinating and tremendously appealing. […] I can see some of Truffaut’s films again and again without growing tired of them”. Indeed, there are some similarities between Scenes from a Marriage and Truffaut’s Domicile conjugal (Bed and Board), which had been released a few years earlier:

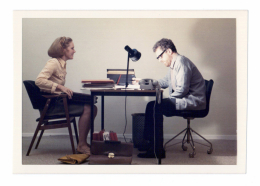

Claude Jade and Jean-Pierre Léaud in Bed and Board (François Truffaut, 1970).

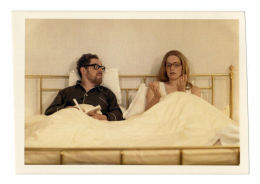

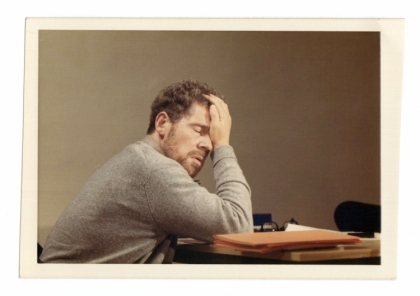

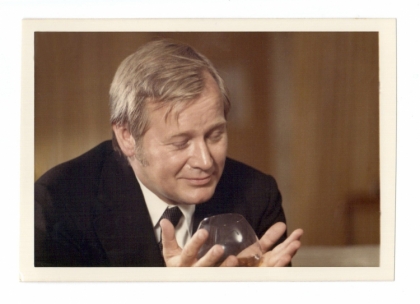

Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann in Scenes from a Marriage (1973). © AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Some shots of Rob Reiner’s When Harry Met Sally (1989) are reminiscent of Scenes from a Marriage. More recently, Asghar Farhadi may have unconsciously referred to Bergman's piece in A Separation. As a matter of fact, the Iranian director stated in a 2012 interview:

After I had completed the film, when I was watching it I suddenly realized that the placement of the camera in the first scene is extremely similar to the placement of the camera in Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage. Bergman is one of my favorite filmmakers and I think so very highly of his work.

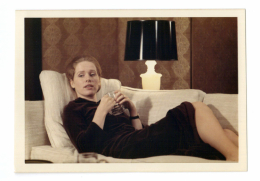

Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan in When Harry Met Sally (Rob Reiner, 1989).

Peyman Moaadi and Leila Hatami in A Separation (Asghar Farhadi, 2011).

As for François Ozon, whose 5 x 2 (2005) also has a clear antecedent in Scenes from a Marriage, he simply stated: “Bergman is for eternity".

© Charlotte Renaud

[The "Legacy" section is written and compiled by Charlotte Renaud. Look here for heirs to other Bergman films.]

Distribution titles

Scener fra et ekteskap (Norway)

Scènes de la vie conjugale (France)

Scenes from a Marriage (USA)

Scenes from a Marriage (Great Britain)

Secretos de un matrimonio (Spain)

Szenen einer Ehe (West Germany)

Production details

Production country: Sweden

Swedish distributor (35 mm): Svensk Filmindustri, Svenska Filminstitutet

Laboratory: FilmTeknik AB

Production company: Cinematograph AB

Aspect ratio: 1,37:1

Colour system: Eastman Color

Sound system: Optical mono

Original length (minutes): 281

TV-screening:

1973-04-11, TV2, Sweden, 49 minutes

1973-04-18, TV2, Sweden, 39 minutes

1973-04-25, TV2, Sweden, 49 minutes

1973-05-02, TV2, Sweden, 49 minutes

1973-05-09, TV2, Sweden, 49 minutes

1973-05-16, TV2, Sweden, 49 minutes

Filming locations

Johan: We're emotional illiterates. We've been taught about anatomy and farming methods in Africa. We've learned mathematical formulas by heart. But we haven't been taught a thing about our souls. We're tremendously ignorant about what makes people tick.

Marianne: Sometimes it grieves me that I have never loved anyone. I don't think I've ever been loved either. It really distresses me.

Johan (Erland Josephson) and Marianne (Liv Ullmann) are the perfect twosome: two houses, two cars, two daughters, two careers. They have the perfect marriage, until one day, they do not. Are we all living in utter confusion? they wonder together; have we missed something important?

Bergman's masterful approach to the dissolution is more an exercise in veneer-stripping than outright dissection. Character revelation is very much in the moment, so we discover the many sides of the prismatic Marianne a little before she does, and suffer the belch that is Johan's burst for freedom. Perfection in cinema may be as suspect as it is in marriage and Bergman here allows at least the affect of artlessness. Due in part to the film's being shot close-in for the television miniseries, there are no sidebars to a haunting past, as in Autumn Sonata, nothing of the warmth and elegance of nature to situate love's labors in a larger context. It makes the film riveting and uncompromising, but also liberating: if there are no big answers, we can't "miss something important".

Collaborators

- Ingmar Bergman, Director and screenplay

- Sven Nykvist, Director of Photography

- Siv Lundgren, Film Editor

- Ulla Stattin, Script Supervisor

- Björn Thulin, Production Designer

- Inger Pehrsson, Costume Designer

- Cecilia Drott, Make-up Supervisor

- Owe Svensson, Production Mixer

- Lars-Owe Carlberg, Production Manager

- Stefan Gustafsson, Gaffer

- Arne Carlsson, Boom Operator

- Lars Karlsson, First Assistant Cameraman

- Anders Bergkvist, Key Grip

- Liv Ullmann, Marianne

- Erland Josephson, Johan

- Bibi Andersson, Katarina

- Jan Malmsjö, Peter

- Gunnel Lindblom, Eva

- Barbro Hiort af Ornäs, Mrs Jacobi

- Anita Wall, Mrs Palm, journalist

- Gunilla Jakobson, Other Crew

- Siri Werkelin, Other Crew

- Adolf Karlström, Other Crew

- Ingrid Bergman, Other Crew

- Kent Nyström, Other Crew