The Seventh Seal

Plague ravages the land as a knight on a spiritual quest plays chess with death.

"One of the most beautiful films ever."Eric Rohmer

About the film

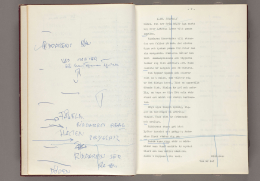

'Bibi's right. I've done enough comedies. It's time for something else. I mustn't let myself get scared off any more. It's better to do this than a bad comedy. I don't give a damn about the money.'

The typical view of Ingmar Bergman is of a brooding intellectual agonising with his inner demons. With hindsight, therefore, it might seem hard for many people to believe that he enjoyed his first major triumphs as a director of comedies. When he wrote the words above in his workbook (the Bibi he names is his partner at the time, the actress Bibi Andersson) he had just had his first international success: his comedy Smiles of a Summer Night had won the jury's special award at the Cannes Film Festival for its 'poetic humour'. Before that, the film had been totally panned by Dagens Nyheter's influential arts editor Olof Lagercrantz, who declared himself ashamed of having seen it. Whether it was this negative reception on the home front or the international success that led Bergman in a new direction is hard to say, but it is clear that The Seventh Seal marks a turning point in Bergman's career, both in artistic and commercial terms. Paradoxically enough, his 'difficult' existential dramas of the latter half of the 1950s became far more successful with international audiences than the more accessible comedies he had served up previously.

Bergman had already passed on his screenplay to his production company Svensk Filmindustri, but it had been refused. Bolstered by his recent success, he made a new attempt:

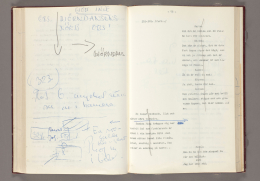

Then I flew down to see the head of Svensk Filmindustri, Carl Anders Dymling. I found him sitting in a hotel room in Cannes, overexcited and out of control, selling Smiles of a Summer Night dirt cheap to any horse trader who happened to show up. [...] I placed the refused screenplay for The Seventh Seal in his lap and said, 'Now or never, Carl Anders!' He said, 'Sure, sure, but I have to read it first.' 'You must have already read it since you turned it down.' 'That's true, but maybe I didn't read it carefully enough.

Dymling eventually gave his consent to the project, yet only granted Bergman a minimal budget and a particularly limited shooting time: 36 days.

Dymling's own recollections differ somewhat:

'As a producer I was quite aware of the financial risk in a motion picture with so serious a theme. But it promised to be unusual, an outstanding picture. It had to be done. We discussed the script for several days and nights during the Cannes festival in May 1956. We agreed on some changes, on the cast and on the budget. We felt as if we were launching a big ship and we were very happy.'

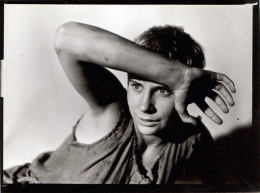

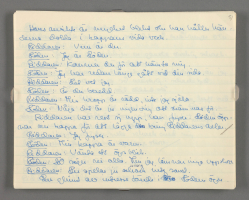

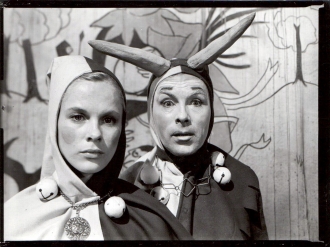

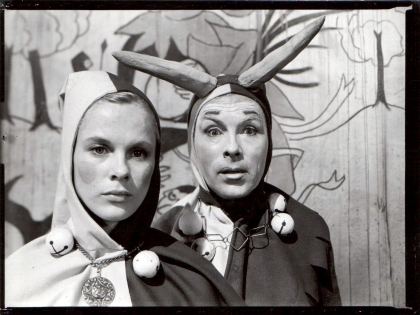

The work started out as a one-act play that Bergman wrote in 1953–1954 as an exercise for the actors at the Malmö Municipal Theatre. He had asked his students to suggest roles they would like to perform, quickly writing a few pages of monologues based on their choices. After the exercise he re-wrote the material as a complete play, Wood Painting, which has many similarities with The Seventh Seal. The main part, however, falls to the squire Jöns, and the knight has smaller role. In this prototype, Death – perhaps Bergman's best-known role ever and played subsequently in The Seventh Seal by Bengt Ekerot – does not feature at all. Wood Painting was first performed for an audience as a radio play 21 September 1954, directed by Bergman himself. Gunnar Björnstrand played his later film role as the squire, while Bengt Ekerot played the knight. In September 195 5, Ekerot directed the play at the Royal Dramatic Theatre, following its première six months earlier on the stage of the Malmö Municipal Theatre, directed by the author (a production in which Björnstrand also played the part of Jöns).

A point worthy of note – and which perhaps confirms that it was with this film that Bergman followed Bibi Andersson's advice to move away from comedy – is that the finished screenplay bears a dedication to her.

Sources of inspiration

On several occasions, Bergman has cited his father's sermons as an important source of inspiration, although not so much, perhaps, for what was actually said. The young Bergman appears to have been more interested in things around him than the sermon itself. Bergman in Images: My Life in Film:

Like all churchgoers have at times, I let my mind wander as I contemplated the altarpieces, triptychs, crucifixes, stained glass-windows, and murals. I would find Jesus and the two robbers in blood and torment, and Mary leaning on St. John: Woman, behold thy son, behold thy mother. Mary Magdalene, the sinner, who had been the last to sleep with her? The Knight playing chess with Death. Death sawing down the Tree of Life, a terrified wretch wringing his hands in the top of it.

Bergman has also mentioned Carl Orff's choral work Carmina Burana, based on medieval songs by itinerant musicians drifting around Europe at the time of the plagues and great wars. "What attracted me was the whole idea of people travelling through the downfall of civilization and culture, bringing birth to new songs. One day when I was listening to the final choral in Carmina Burana, it suddenly struck me that I had the theme for my next film!"

In an interview he has also cited Picasso's 1905 painting Les Saltimbanques and Dürer's etching Knight, Death and the Devil.

Bergman himself has always been sparing when it comes to revealing literary inspirations for the film, but several critics have named August Strindberg's Saga of the Folkungs (some were of the opinion that it was a medieval drama along similar lines to Strindberg's, whereas others saw the film as unabashed plagiarism). In an ambivalent review, Expressen's Ivar Harrie wrote that Bergman is "the Swedish champion of pretentious trash", at the same time as being a "great poet, a poet of images." He continues:

[...] Bergman wants to be the play actor, the jester in the marketplace, yet do not forget that he also wants to be a popular – a very popular – revivalist. He expresses himself with equal vulgarity in both roles, and with equal authenticity. [...] He has discovered that film as an art form means both the return of the jester and of the preaching mendicant friar. In a nutshell, his ambition is to be Sweden's Kaj Munk. This is an ambition that may appear presumptuous. Yet Ingmar Bergman is welcome to have it.

But the origins of The Seventh Seal can also be traced to Bergman's own oeuvre. In addition to Wood Painting, (mentioned above) a number of passages in his early works are reminiscent of scenes in the film. In his play The Death of Punch, for example, which he directed and staged for the Stockholm Student Theatre in 1942, there is a scene in which the principal character Punch is confronted by two men carrying a coffin. Words are exchanged, strikingly similar to the lines in The Seventh Seal where Death saws down the tree that holds the actor Skat. (This comparison was made by Maaret Koskinen in her book In the Beginning was the Word.) Maaret Koskinen also observes that the final stage directions for The Day Ends Early from 1946 (based on a screenplay that was never filmed, The Comedy about Jenny) bear similarities to the conclusion of The Seventh Seal. 'Slowly they go out into the darkness. They disappear one by one. Finally, only darkness and the storm remain.' As Egil Törnqvist has pointed out, there are also thematic similarities. 'The Day Ends Early thematically relates to The Seventh Seal. Mrs Åström, the messenger of Death, tells various people that they will die at a certain time the following day.'

In terms of cinematic precedents, the witch-burning scene has drawn comparisons with a similar scene in Carl Theodor Dreyer's Day of Wrath, but if this is a conscious reference, Bergman himself has never mentioned it. In an interview with the French film critic Jean Béranger, Bergman was asked whether Jean Cocteau's Orphée had been in his mind. His response was:

'I consider Orphée one of the most beautiful French films ever made, at least of those that I've seen. I liked less Beauty and the Beast, which seemed to me too contrived. And to speak of a German influence is to commit an inaccuracy. The silent Swedish masters – imitiated in their own time by the Germans – they alone have inspired me, in the very first place Sjöström whom I consider one of the greatest filmmakers of all time.'

Finally, the most obvious source of inspiration for this theological film par excellence is, of course, the Bible. The title itself, as so often in Bergman, is a biblical quotation, from the Book of Revelation (the film opens with the full text). "And when he had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour. And I saw the seven angels which stood before God; and to them were given seven trumpets." (Revelation 8:12)

Shooting the film

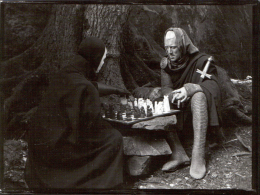

Shooting began on 2 July 1956. With one or two exceptions - such as the celebrated introductory scenes filmed at Hovs hallar in Skåne (in the south of Sweden) – the entire film was shot at the Råsunda Film Studios. Cinematographer Gunnar Fischer recalls that shooting the introduction scene caused a number of problems: simply carrying a 100 kg camera down to the pebble beach was a feat in itself. Given the technological restraints, it is hardly surprising that so many films at that time were shot in the studio.

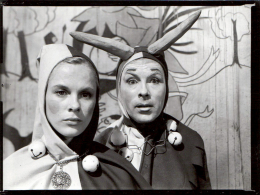

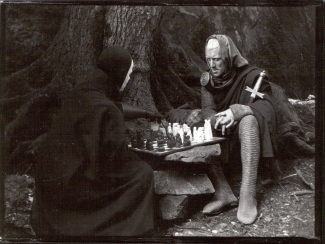

On the subject of the lighting for the most famous of all the scenes in the film, in which the knight plays chess with Death, Fischer remarked: 'You can see that each of them has a 2 kg lamp behind him, illuminating his profile. People said to me that that has to mean that there are two suns. 'Yes. That's quite right,' I said. But if you can accept Death sitting playing a game of chess, then you can also accept two suns [...

]'

Yet chance events also play a part in great photographic art, as Mårten Blomkvist recorded in an interview with Fischer:

In one scene Nils Poppe's band of players meet the corpse plunderer Raval (Bertil Anderberg) in the forest. Raval has finally succumbed to the plague. Terror-stuck, the players follow Raval's, long, wild, and stifling struggle with death in a forest glade. Finally he collapses and falls down dead.

At that point the clouds part, and the sun shines down in a kind of redeeming light over the trees, the earth and the corpse plunderer, now a corpse himself.

We now know how the scene evolved from behind the camera. With his eye pressed to the viewfinder, Fischer followed Raval's struggle with death. When Bertil Anderberg had fallen down, the scene was over. Fischer got ready to stop filming.

Yet Bergman's customary "thanks" was not forthcoming. 'Had the director fallen asleep?', Fischer wondered – yet dutifully he let the camera continue to roll.

At that point there was a break in the clouds. From where he was, Fischer had not been able to see it coming. Light streamed into the picture, an unexpected bonus.

Since then, many people have wondered just how that effect was achieved.

'It was pure luck' Gunnar Fischer said, banging the table in front of him. 'Just imagine if I'd stopped filming there and then...'

And at that moment, almost forty years later, one could sense that he could still hardly bear to think of the split second when he almost shut down his camera in that forest glade in the Råsunda studios.

Bergman has also told of some fairly chaotic moments during the shooting, as in the scene where they burn the witch. Bergman in Images: My Life in Film:

The place of execution was a little further down the yard; so we could only shoot from one side, the tower blocks being on the other. When the time came for me to inspect the heap of firewood, a crowd of little urchins were already there, clambering up on the fence and asking: 'When's the execution going to be, Mister?' So I said: 'We're starting at seven this evening.' And one little chap said: 'Then I'll go home and ask my mum if I can stay up a bit later!'

Things like that were all part of our way of shooting films in those days. It was as bohemian as that. Out at Solna we had the youngest fire-captain in Sweden, generally known as Squirt-Olle. He was given orders to prepare the bonfire. Squirt-Olle turned out to be an inverted pyromaniac of the first order. For a week he put his whole heart and soul into preparing that bonfire. We'd arranged a fantastic camera-angle from above the bonfire and the girl hangin at the stake, and Gunnar Björnstrand and Max von Sydow and the cart with Åke Fridell, Bibi, Nils Poppe and Gunnel Lindblom in the background; plus the soldiers, of course, who had to light the bonfire. At exactly the right moment for exposure in the twilight I shouted 'action'. And out came Squirt-Olle and set fire to it and puff! not only we, but the whole of Solna, were swathed in a cloud of smoke stretching as far as Haga South. I was standing on a crane yelling 'Max, where are you?' And the stallion Fridell should have been riding, that was found right down by the pavilion, with Fridell hanging on behind. The trans all came to stop, and for several week afterwards all the housewives of Solna were cleaning oil off their window-panes.

The final scene, one of the most famous in cinema history, in which Death leads his victims in a danse macabre, was also subject to the vagaries of chance. As Bergman recalls in Images:

'The final scene when Death dances off with the travellers was shot at Hovs hallar. We had packed up for the day because of an approaching storm. Suddenly I caught sight of a strange cloud. Gunnar Fischer hastily set the camera back into place. Several of the actors had already returned to where we were staying, so a few grips and a couple of tourists danced in their place, having no idea what it was all about. The image that later became so famous was improvised in only a few minutes.'

Epilogue

Shooting came to an end on 24 August 1956. The job of editing was given to Lennart Wallén, in Bergman's eyes, a safe pair of hands. Wallén edited four of his films in total, though none of them with such reverence as The Seventh Seal. Despite its low budget, The Seventh Seal had turned into something of a prestige project for SF, where 50th anniversary celebrations were set to coincide with its premiere. Bergman has painful recollections of the event:

At Svensk Filmindustri, The Seventh Seal suddenly became part of the pomp and circumstance of an anniversary celebration focusing on the golden age of Swedish film. This was a catastrophe for the film; it was not made for such activities. The gala première held a murderous atmosphere for a serious art film complete with a society audience, a flourish of trumpets, and a speech by Carl Anders Dymling. It was devestating. I did what I could to stop the onslaught but ultimately was powerless. Their boredom and their malice poured relentlessly over everything.

The reviews were mostly positive, effusive even, but there were one or two that were extremely negative. The review in Expressen (cited earlier) basically sums up the way the film was received, namely that Bergman was praised as an image maker and disparaged as a writer. Professor of Literature John Landqvist insisted that Bergman had plagiarised Strindberg, whilst the writer (and budding film director) Vilgot Sjöman came to his friend's defence.

Internationally the film was received with almost universal praise. In France Eric Rohmer pronounced it "one of the most beautiful films ever made" and the American film critic Andrew Sarris called it an 'existential masterpiece'.

The Seventh Seal went on to win a number of international awards, including the French Film Academy's Grand Prix International d'Avant-garde.

As a point of reference in other films, The Seventh Seal is in a class of its own among Bergman's films. The image of Death in human form has made a remarkable journey from European art cinema to international popular culture. The reason is, of course, the countless paraphrases and parodies in films like Woody Allen's Life and Death (1975), Monty Python's The Meaning of Life (1983), Peter Hewitt's Bill and Teds Bogus Journey (1991) John McTiernan's The Last Action Hero (1993), starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Pablo Berger's Torremolinos 73 (2003).

In the documentary A Decade Under the Influence about the ways in which American films of the 70s drew inspiration from European art house films, a sequence with Death from The Seventh Seal is shown to the accompaniment of the Rolling Stones' "Street Fighting Man"!

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives.

- Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film.

Bergman's most famous film takes much of its imagery from medieval art. Thus, the vision of a man playing chess with Death was inspired by Albertus Pictor’s paintings. However, here again, remember that Bergman was first and foremost a man of the theatre. Just prior to shooting, he directed, as a radio play, Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Everyman, whose main theme is – an encounter with Death. The opening scene became a source of inspiration for many film-makers, such as David Lynch.

In Lost Highway as in The Seventh Seal, Death is dressed in black, whiteface; when he first appears, among the guests at a party, the room falls silent. The question asked by this “Mystery Man” in Lynch’s film – "We have already met, haven't we?" – echoes Death's first words to the Knight in Bergman’s film: “I´ve already been with you for a long time”. However, Death in Lost Highway has a demonic aspect and mocking smile, whereas in The Seventh Seal, he is “neutral” and seems to take no pleasure in killing.

John Boorman and Terry Gilliam have acknowledged the influence of The Seventh Seal on their work, and Paul Verhoeven has remarked: "It made me realize that films can be art. It inspired me to become a film director. This is one of the most powerful and significant films ever made."

This iconic film has been the subject of numerous pastiches and parodies, among them Woton’s Wake, Brian de Palma’s student movie, full of filmic allusions from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to The Seventh Seal.

As for Woody Allen, he has referenced the film in two of his own, Love and Death and Deconstructing Harry. In a 1988 New York Times interview, he stated that “The finale, as Death dances off with all the doomed people to the nether lands, is one of the most memorable shots in all movies".

© Charlotte Renaud

[The "Legacy" section is written and compiled by Charlotte Renaud. Look here for heirs to other Bergman films.]

Distribution titles

A hetedik pecsét (Hungary)

Seitsemäs sinetti (Finland)

Le septième sceau (France)

El séptimo sello (Spain)

Il settimo sigillo (Italy)

The Seventh Seal (Great Britain)

The Seventh Seal (USA)

Das siebente Siegel (West Germany)

Det syvende segl (Denmark)

Det syvende seglet (Norway)

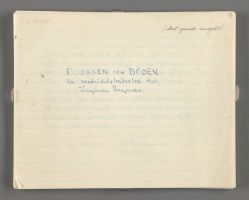

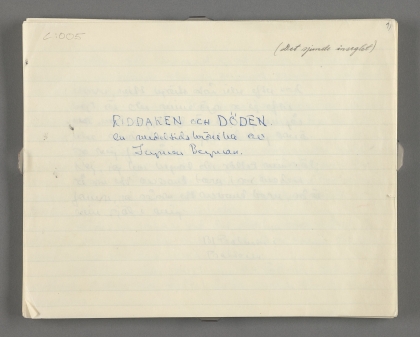

Working title: Riddaren och döden (The knight and the death)

Production details

Production country: Sweden

Distributor in Sweden (35 mm): Svensk Filmindustri, Swedish Film Institute

Distributor in Sweden (rental video) (physical): Swedish Film Institute

Laboratory: FilmTeknik AB

Production company: Svensk Filmindustri

Original work: Wood Painting (Play) by Ingmar Bergman

Aspect ratio: 1,37:1

Colour system: Black and white

Sound system: Optical mono

Original length (minutes): 96

Censorship: 089.285

Date: 1956-12-12

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2620 metres

Censorship: 089.285

Date: 1963

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2620 metres

Censorship: 089.285

Date: 1976

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2620 metres

Release date: 1957-02-16, Röda Kvarn, Sweden, 96 minutes

Filming locations

Sweden (1956-07-02-1956-08-24)

Filmstaden, Råsunda

Hovs hallar, Torekov, Båstad

Östanå in Roslags-Kulla, Österåker

Viby by, Sigtuna

Skeviks grotta in Gustavsberg, Värmdö

Skytteholm, Ekerö

Music

Title: Hållas mellan rona

Composer: Erik Nordgren (1957)

Lyrics: Ingmar Bergman (1957)

Singer: Gunnar Björnstrand

Title: Det sitter en duva

Composer: Erik Nordgren (1957)

Lyrics: Ingmar Bergman (1957)

Singer: Nils Poppe

Title: Ödet är en rackare

Composer: Erik Nordgren (1957)

Lyrics: Ingmar Bergman (1957)

Singer: Gunnar Björnstrand

Title: Hästen sitter i trädet

Composer: Erik Nordgren (1957)

Lyrics: Ingmar Bergman (1957)

Singer: Nils Poppe, Bibi Andersson

Title: Dies iræ, dies illa Alternative title: Vredens stora dag är nära

Lyrics: Tomas of Celano (Latin lyrics) Severin Cavallin (Swedish lyrics 1882)

Arrangement: Johan Bergman (Swedish lyrics arrangement 1920) Natanael Beskow (Swedish lyrics arrangement 1920)

Title: Skats sång Alternativ titel: Jag är en liten fågel lätt ...

Composer: Erik Nordgren (1957)

Lyrics: Ingmar Bergman (1957)

Singer: Erik Strandmark

It may be folly to think that life and thus death hold any secrets. In The Seventh Seal Bergman spoke to this modern query in a medieval setting rendered at once awesome and intimate in chiaroscuro.

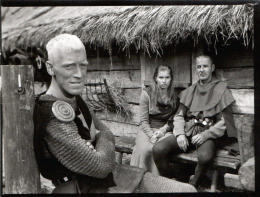

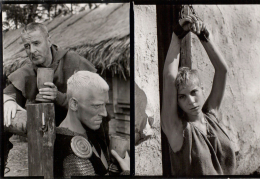

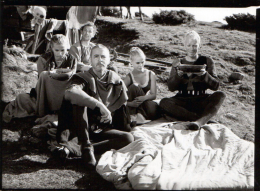

A knight, Antonius Block (Max von Sydow), and his squire Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand) return disillusioned from the Crusades to the hysteria of plague-infested fourteenth-century Sweden. On the shore Block encounters Death and, in one of the most effective reverse-angle exchanges ever filmed, challenges him to a game of chess, playing for time to perform one significant act in life.

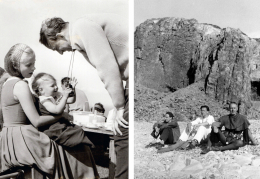

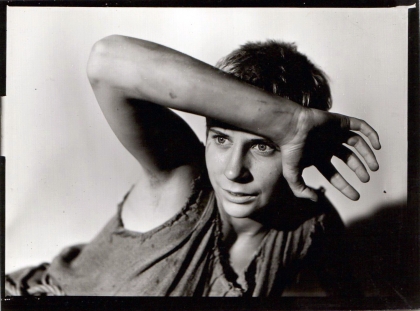

What is timeless about this existential passion play is the humanity of its characters, who seem to shun allegory like a kind of narrative death: Block, whom the Crusades took away from the real-the only proof of God – to the abstract, and torment; Jöns, cynical sensualist who articulates the void; Death himself, a picture of inconclusiveness; and the dreamer Jof and his wild-strawberry wife (Bibi Andersson), actors traveling into light.

Collaborators

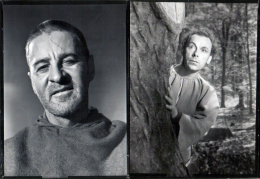

- Ingmar Bergman, Director and screenplay

- Gunnar Fischer, Director of Photography

- Lennart Wallén, Film Editor

- Katinka Faragó, Script Supervisor

- Manne Lindholm, Costume Designer

- Nils Nittel, Make-up and hair

- P.A. Lundgren, Art Director

- Else Fisher, Choreography

- Erik Nordgren, Composer

- Sixten Ehrling, Orchestra Leader

- Aaby Wedin, Production Mixer

- Allan Ekelund, Production Manager

- Carl-Henry Cagarp, Unit Manager

- Åke Nilsson, Assistant Cameraman

- Lennart Olsson, Assistant Director

- Ove Svensson, Assistant Director

- Lennart Wallin, Boom Operator

- Louis Huch, Still Photographer

- Max von Sydow, The knight Antonius Block

- Gunnar Björnstrand, Jöns, the knight's squire

- Nils Poppe, Jof, jester

- Bibi Andersson, Mia, Jof's wife

- Bengt Ekerot, Death

- Åke Fridell, Plog, blacksmith

- Inga Gill, Lisa, Plog's wife

- Erik Strandmark, Jonas Skat

- Bertil Anderberg, Raval

- Gunnel Lindblom, The mute girl

- Maud Hansson, The witch

- Inga Landgré, Karin, Block's wife

- Gunnar Olsson, The church painter

- Anders Ek, The monk who speaks to the villagers

- Lars Lind, The young monk

- Benkt-Åke Benktsson, The merchant at the inn

- Tor Borong, Peasant at the inn

- Gudrun Brost, The maid at the inn

- Harry Asklund, The innkeeper

- Ulf Johanson, Knight commander

- Sten Ardenstam, Knight

- Gordon Löwenadler, Knight

- Karl Widh, Flagellant with crotches

- Tommy Karlsson, , Mikael, Jof and Mia's son

- Siv Aleros, Flagellant

- Bengt Gillberg, Flagellant

- Lars Granberg, Flagellant

- Gunlög Hagberg, Flagellant

- Gun Hammargren, Flagellant

- Uno Larsson, Flagellant

- Lennart Lilja, Flagellant

- Monica Lindman, Flagellant

- Helge Sjökvist, Flagellant

- Georg Skarstedt, Flagellant

- Ragnar Sörman, Flagellant

- Lennart Tollén, Flagellant

- Caya Wickström, Flagellant

- Catherine Berg, Young woman kneeling for the flagellants

- Mona Malm, Young pregnant woman

- Tor Isedal, Man

- Josef Norman, Old man at the inn

- Gösta Prüzelius, Man

- Fritjof Tall, Man

- Nils Whiten, Old man addressen by the monk at the flagellant procession

- Lena Bergman, Girl at the inn

- P A Lundgren