Saraband

The aging Marianne visits her ex-husband and ends up in the middle of a gut-wrenching family feud.

"This is a testament of love and anguish from the man who used to be called the greatest living filmmaker. Well, dammit, he was. And, as proves, he still is."Richard Corliss in Time Magazine

About the film

On 25th October 2001 the Swedish press announced a sensation: 'Ingmar Bergman is filming again!' According to Sydsvenska Dagbladet the work in question was 'a follow-on from the classic television series Scenes From a Marriage. Working title: Anna'. There was great secrecy surrounding the project, it was claimed.

On the following day, Expressen followed up the story with an interview with Ann-Kristin Westerberg, head of the international department of Svensk Filmindustri. Bergman had told her that the film was originally intended as 'nine dialogues for any chosen medium'. This was a working method that Bergman had been using for some considerable time: After the Rehearsal, The Last Gasp and many other of his later films might just have easily remained as works of literature.

Bergman himself was to liken the method to the format of Bach's harpsichord sonatas: 'They can be played by string quartets, wind ensembles, on the guitar, organ or piano. I've written in the way I've been accustomed to writing for more than fifty years it looks like a play, but it could just as easily be a film, television programme or simply something to read.'

The Expressen article also denied early reports that the work was to be a 'continuation' of Scenes From A Marriage: 'even though Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann still have their role names Johan and Marianne, it's not about what happened thirty years on,' Bergman informed the world via his provisional mouthpiece, Westerberg.

Sources of inspiration

In 2000 Liv Ullmann directed Faithless, in which Erland Josephson played a supporting role. Shooting took place on Fårö, so it was natural that memories from the filming of Scenes From a Marriage would surface. In between takes, waiting for precisely the right light, the old friends Ullmann and Josephson would walk along the beach and play at being Johan and Marianne once again, thirty years later.

'We played them as older and no wiser', Liv Ullmann explains, 'Joakim Strömholm filmed us, we gave the footage to Ingmar and one year later there was a screenplay!'

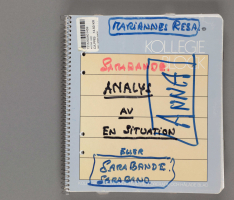

For a long time the film had the working title 'Anna' (previously mooted titles included 'Marianne's Journey' and 'Analysis of a Situation'). The eventual title has its origins in a Spanish dance for couples often performed in European courts during the Baroque era. In all of Bach's cello suites there is a saraband, and the film uses the saraband from his fifth suite. Bergman had used this piece previously Cries and Whispers.

Yet in Saraband it is possibly even more apt, since the film is structured as a series of episodes, each comprising a tense dialogue between two people. In its format, Saraband is one of Bergman's most uncompromising works: a masterpiece along strict musical/mathematical lines, conceived by a man in his eighties.

In Saraband Bergman revisits much of his earlier repertoire, and even his own private life. This, his last film, may also be his most personal of all. Take, for example, the photograph of the dead Anna (Henrik's wife and Karin's mother). As a stylistic device, this is familiar from other films in which a portrait of a dead woman symbolises her continuing influence: Alfred Hitchcock's Rebecca, Otto Preminger's Laura, or Alf Sjöberg's Miss Julie. Yet in Saraband the device reaches a new plane: the woman in the photograph is Ingmar Bergman's actual wife Ingrid, who died of cancer in 1995.

Similarly, a black and white photograph of the farm where Johan is supposed to live is actually a picture of the house that Bergman so loved to visit as a child: his grandparent's summer house 'Våroms' in Dalarna.

In addition to these personal references, Bergman's other films and productions spring readily to mind. Apart from the obvious Scenes From a Marriage, we find the mirroring of the destructive parental conflicts of many previous films, the Dalarna landscapes of The Virgin Spring, the catatonic daughter in Autumn Sonata, the curmudgeonly yet anguish-ridden patriarch from Wild Strawberries, the implied theme of incest from Through a Glass Darkly and so on. Saraband is, quite simply, a good point from which to enter Ingmar Bergman's universe.

Shooting the film

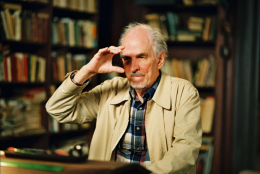

Whilst Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann got to revive their roles as Johan and Marianne, the parts of Henrik and Karin were played by Börje Ahlstedt and Julia Dufvenius. Ahlstedt had undertaken a number of heavyweight roles for Bergman previously: as Uncle Carl in Fanny and Alexander, The Best Intentions and In the presence of a Clown, as Claudius in Hamlet, and as the eponymous hero of Peer Gynt.

Dufvenius, on the other hand, was relatively new to Bergman; her only previous collaboration with the director was a minor role in his stage production of Maria Stuart a few years previously. Yet according to Bergman himself, who had been working on the screenplay for some time, he had already decided that Dufvenius was right for the part.

Julia Dufvenius had no idea of this, so she was somewhat taken aback, a couple of years later, when her vacuum cleaning was interrupted by a telephone call from Bergman. He had, he told her, written a play, and thought of her as he was writing one of the parts. Would she care to take it? She would indeed, but she felt compelled to ask him how he could know her so well that he could base an entire part around her. He'd 'seen her in a television series', he replied (Glappet), but he couldn't remember what it was called...

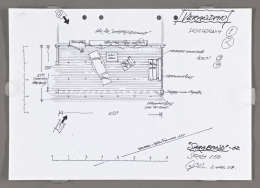

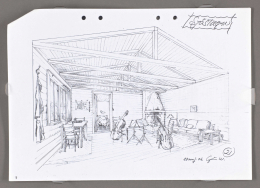

Saraband was filmed using digital technology. Sveriges Television were informed about a completely new HDTV camera, the Thomson 6000, and decided to try it. So new was it that there were only five of the cameras in the whole world, four of which were rented by SVT: three for shooting and one as a back up. Bergman was initially impressed by the new HDTV technology. The film turned out to be the world's first television production using three camera HD, quite remarkable given Bergman's venerable age.

Yet this new technology was to prove a challenge both for the director, accustomed as he was to analogue production, and his crew. Press reports spoke of Bergman's anger at the cameras, especially at the noise they generated. HD cameras have in-built fans to keep their electronic gadgetry cool, and this for Bergman was a step backwards: it reminded him of the awkward cameras he was forced to use in his youth: 'We had a French Debrie camera. We could only suppress the noise with lead, so it got really heavy to carry around. We had to have a large cover to put over the camera to stop the noise being picked up on the sound tape. Those covers have followed me through the film business all my life.'

It was true, because once again they had to use a sort of cover: they surrounded the cameras in sound insulation material from a sound control room that was being refurbished. Worst of all, the sound problems meant that they had to abandon the three camera method that Bergman had planned the film around so carefully, and revert to a single camera.

Bergman's fixation with the sound of the cameras might appear somewhat obsessive, but it does have its reasons. Firstly the special nature of the film itself: 'There are always two people in the shot who are confronted with each other, and that makes it important that their voices can be heard properly, with all the nuances of the human voice.' Another reason was the director's well documented acoustic oversensitivity:

'My right ear has been totally ruined since my military service when I had to fire a number 14 machine gun. But I still hear the crickets with my left ear. In my right eye I have very little sight remaining, but I see like a hawk with my left eye.'

When they finally solved, or reconciled themselves to, the problems, the remainder of the shoot went well. But as Bergman would later describe the digital experience he was forced to endure: 'It's like the Swedish fighter plane JAS: full of technological refinements, yet not suitable for use in actual warfare.'

Epilogue

The film was premiered on Sveriges Television's Channel 2 on 3rd December 2003. A few days after the premiere, Dagens Nyheter was able to announce with barely disguised relief that Saraband had attracted 990,000 viewers, a figure comparable to the popular soap of the time, Skeppsholmen, the latest episode of which had been seen by 755,000 people. History can never tell then extent of audience overlap between the two programmes, yet SVT regarded Saraband as an resounding success.

The film's reception in terms of reviews and comments varied widely in the Swedish press. Generally speaking, critics in the rural press were critical, often poking fun at Saraband, whereas those in the larger cities offered a deeper analysis of the film and were more favourable in their judgement.

In her review in Svenska Dagbladet, Astrid Söderbergh Widding draws a thought-provoking conclusion regarding the reception of Saraband:

'There are risks in bidding a multiple farewell, as Bergman has done: firstly, his farewell to film as a medium in Fanny and Alexander, followed by a number of comebacks as a screenwriter, and now finally (can we really believe it?) his farewell to television drama. Those who spoke warmly of the mature Bergman's exuberance in Fanny and Alexander will most probably find the pared-down expression of his last work more difficult to appreciate.'

It is obvious that Saraband did not achieve the popular appeal of Fanny and Alexander, nor indeed of its direct precursor Scenes From a Marriage. Saraband is complex in structure, will virtually no nods to conventional realism, and as such it places much greater demands on the viewer. Anyone who had been expecting a continuation of Scenes From a Marriage, in many respects more accessible, would have been disappointed.

The film's reception abroad, on the other hand, was something completely different. For Bergman aficionados there was a sense of déjà-vu: the unfavourable reception in Sweden of a film from the 50s such as Smiles of a Summer Night was the exact opposite of the praise heaped on the film abroad.

In France, the first country to screen the film in the cinema, it was greeted by a virtually unanimous group of critics as a 'chef-d'oeuvre', a masterpiece. One reviewer wrote: 'With his familiar themes of love, death, hate and the family, Bergman touches on the sublime.' Saraband was also nominated for best European film in the French César Awards in 2005.

Writing in Le Nouvel Observateur, Pascal Mérigeau noted: 'I do not know if there is a cineast in the world who does not regard Bergman as the greatest of all. With Saraband the master has delivered the ultimate work, the sum of all sums, the absolute work.'

A reporter for Télérama who travelled to Sweden declared himself amazed at the level of indifference in Sweden: 'The Swedes are keeping silent: Saraband? It's a whole year since it was shown on television, it's passé! And Bergman is, too...'

In the USA, where the film was also shown in cinemas, the reception was somewhat more mixed, yet generally positive. In Time Richard Corliss called the film 'sublime' and referred to Bergman as the world's foremost living director. Others compared Saraband with works by Ibsen and Dreyer (Scandinavian comparisons which, strangely enough, appear to have been ignored by the Swedish critics). Most enthusiastic of all was the Christian Science Monitor, which called it the best film of the year, perhaps the best film of the century so far. For his role as Henrik, Börje Ahlstedt was spoken of enthusiastically in the run-up to the Oscar nominations, something rather unusual for an actor in a non-English language film.

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives.

- Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film.

- Ingmar Bergman, The Fifth Act.

- Richard Corliss, Time, 17 December 2005.

- "Cecilia Hagen mötte den evigt unge Ingmar Bergman", Expressen, 3 June 2003.

- "Cecilia Hagen möter Julia Dufvenius", Expressen, 30 November 2003.

- Pascal Mérigeau, Le Nouvel Observateur, 8 December 2004.

- Betty Skawonius, "Kaos är granne med Bergman", Dagens Nyheter, 14 July 2004.

- Lasse Svanberg, "IB möter Hi-Tech", TM 35, nr. 3, 2003.

- Frédéric Strauss, "Bergman: L'ombre du commandeur", Télérama, 8 December 2004.

- Astrid Söderbergh Widding, "Ett obönhörligt fullbordande", Svenska Dagbladet, 1 December 2003.

Stephen Holden in New York Times:

As ever, women are the salvation of men. They alone have the capacity to forgive and empathize, even after their terrible mistreatment at the hands of the opposite sex. And men, no matter how accomplished and feted by the world, remain hard-bitten patriarchal taskmasters vainly striving to rule their pitiful little fiefs.

Strictly Film School:

Saraband retains the penetrating, distilled intensity of Bergman's late period masterworks but infused with the unsentimental, but gentle humor of distanced perspective and thoughtful reflection. Rather than a nostalgic swan song, Bergman has created another provocative chapter in his enduring expositions into the most fundamental human need for connection.

Distribution titles

Sarabande (Norway)

Production details

Working title: Anna

Production country: Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Italy, Finland, Germany

Pre-production subsidy: Nordiska TV-samarbetsfonden, Nordisk Film- & TV Fond

Production company: Sveriges Television AB, Danmarks Radio, Norsk Rikskringkasting, Radiotelevisione Italiana, Yleisradio Ab

TV1, Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, Österreichischer Rundfunk, ZDF Enterprises GmbH, Network Movie Film- und Fernsehproduktion GmbH & Co. KG

Colour system: Colour

TV-screening: 2003-12-01, SVT1, Sweden, 110 minutes

Music

Title: Suite, violon cello, BWV 1011, no 5, c-minor. Movement 4 (Sarabande)

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach (around 1720)

Instrumentalist: Torleif Thedéen

Title: Triosonat, organ, BWV 525, no 1. Movement 1 (Allegro)

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach (ca 1727)

Instrumentalist: Torvald Torén

Title: Symfoni, no 9, WAB 109, d-minor. Movement 2 (Scherzo)

Composer: Anton Bruckner (composed 1887-1896)

Dirigent: Herbert Blomstedt

Title: Koralpreludium, BWV 1117, "Alle Menschen müssen sterben"

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach (1708)

Instrumentalist: Hans Fagius

Title: Kvartett, stings, no 1, op. 51:1, c-minor

Composer: Johannes Brahms

Marianne: And you?

Johan: Can't complain. But sometimes I look at my voluntary isolation and think I'm in hell. That I'm already dead, though I don't know it. But I'm fine. I've ransacked my past, now that I have the answer sheet.

Marianne: That doesn't sound like much fun.

Johan: Precisely Marianne, it isn't. But who the hell said damnation was supposed to be fun?

Johan: An old priest once told me that a good relationship has two components: a good friendship and unshakeable eroticism. No one can say you and I weren't good friends. Kind and capable.

Marianne: Good friendship.

Johan: Absolutely.

Marianne: You were faithless.

Marianne: I realised suddenly that I was the world's must fooled and betrayed wife and lover. Johan was notoriously and compulsively unfaithful.

Johan: Honest hate should be respected, and I do, but I don't give a damn if you hate me. You barely exist. If you didn't have Karin, who, thank God, takes after her mother, you wouldn't exist for me at all. There is no hostility here, I promise you.

Henrik: He has a fortune and he won't die. He's probably mummified by his own nastiness.

Johan: Henrik consistently fails at everything. He can't even kill himself.

Johan: I think it's some kind of anxiety?

Marianne: Anxiety? What kind of anxiety? Now I see. You're sad.

Johan: I'm not sad. It's worse. It's a hellish anxiety. It's bigger than I am. It's trying to push its way out of me through every orifice, my eyes, my skin, through my arse. It's like a gigantic, total mental diarrhoea.

In Saraband, Marianne and Johan meet again after thirty years without contact, when Marianne suddenly feels a need to see her ex-husband again. She decides to visit Johan at his old summer house in the western province of Dalarna. And so, one beautiful autumn day, there she is, beside his reclining chair, waking him with a light kiss.

Also living at the summer house are Johan's son Henrik and Henrik's daughter Karin. Henrik is giving his daughter cello lessons and already sees her future as staked out. Relations between father and son are very strained, but both are protective of Karin. They are all still mourning Anna, Henrik's much-loved wife, who died two years ago, yet who, in many ways, remains present among them. Marianne soon realizes that things are not all as they should be, and she finds herself unwillingly drawn into a complicated and upsetting power struggle.

Collaborators

- Ingmar Bergman, Director and screenplay

- Raymond Wemmenlöv, Director of Photography

- Sofi Stridh, Director of Photography

- Stefan Eriksson, Director of Photography

- Per-Olof Lantto, Director of Photography

- Jesper Holmström, Director of Photography

- Sylvia Ingemarsson, Film Editor

- Kerstin Sundberg, Script Supervisor

- Inger Pehrsson, Costume Designer

- Cecilia Drott, Make-up and hair

- Göran Wassberg, Production Designer

- Rasmus Rasmusson, Propman

- Åsa Forsberg-Lindgren, Musician

- Per Sturk, Gaffer

- Lars Ståhlberg, Gaffer

- Håkan Sanchis, Construction Coordinator

- Jan Stenmark, Graphics

- Ulla Örn Smith, Graphics

- Ulf Olausson, Supervising Sound Editor

- Carl Edström, Supervising Sound Editor

- Anders Degerberg, Supervising Sound Editor

- Per Nyström, Supervising Sound Editor

- Erik Näsman, Production Mixer

- Göran Nylander, Production Mixer

- Börje Johansson, Production Mixer

- Adrian Wester, Key Grip

- Kimmo Rajala, Stunt Coordinator

- Pia Ehrnvall, Project Leader

- Sven Jarnerup, Assistant Cameraman

- Torbjörn Ehrnvall, Assistant Director

- Jesper Svedin, Assistant Film Editor

- Inger Eiserwall, Assistant Costume Designer

- Åsa Persson, Assistant Production Designer

- Jan-Erik Savela, Property Master

- Per Sundin, Lighting Supervisor

- Mike Tiverios, Steadicam Operator

- Mats Holmgren, Color Timer

- Ulf Nordin, Color Timer

- Teddy Holm, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Gábor Pasztor, Re-recording Mixer

- Ann-Mari Langer, Production Accountant

- Gylla Ersson, Press Agent

- Brita Sylvén, Press Agent

- Bengt Wanselius, Still Photographer

- Liv Ullmann, Marianne

- Erland Josephson, Johan

- Börje Ahlstedt, Henrik, Johan's son

- Julia Dufvenius, Karin, Henrik's daughter

- Gunnel Fred, Martha

- Irene Wiklund, Other Crew

- Karin Söderberg, Other Crew

- Ola Westman, Other Crew

- Hanna Pauli, Other Crew

- Monica Danielsson, Other Crew