[Notes on High Tension]

Director’s copy of the script to High Tension, filled with Bergman’s notes on a film he would come to loathe (and seems to have disliked from the very beginning).

About the text

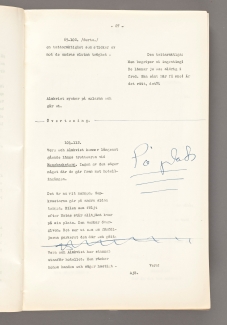

Herbet Grevenius may have written the screenplay for High Tension, but this director’s copy of the script contains Bergman’s handwritten notes and scenery sketches. Bergman’s distaste for this film is no retrospective construction, as illustrated by his notes: “We began this production on the 6th of July. It is with a frenzied yearning that I look forward to the 15th of August [the last day of filming].” Elsewhere, he lays out the following:

All of this began with reluctant boredom: it was to be a simple piece of workmanlike product. Nothing to be proud of, but sometimes that’s just how it goes with film. But now, today, on the Wednesday before Midsummer – I don’t know what the date is today and can’t be bothered to figure it out – I recall feeling a sense of vague unease but also a sense of curiosity and excitement over the novelty of it all.

The casting of course will be fun. Kjellin, Hasso, the Danish Ebbe Rodhe. But I’ll probably miss my own favourite implements: Maj-Britt, Birger, Stig et cetera.

There’s nothing courageous about making a film like this one. Nothing at all. Nothing inviting except for a few bits. Not real like Harbour City, where I could tell myself, “This is blood-spattered reality, this has happened. This is human suffering, torment, but also greatness.”

This film is about phantom characters in a phantom world which bears a vague resemblance to the city of Stockholm. I suppose that’s why everyone thinks the story is so great. Because it’s so incredibly inoffensive.

I may lose all my integrity on this project, but if so, I pray to God that at least my company will earn a ton of money. So that I can continue with my disorderly balancing act on the outskirts of reality. It’s not without that I long to return. God, I’ve been well-behaved. Full of compromises. Except for Prison, but that was no good since it was just made-up (just like Herbert said that one time). Woman Without a Face was a disgusting product.

Strictly speaking, I feel that I’m forced to give the entirety of my earlier work a failing grade. There may have been particulars, but it’s just splinters, shards of glass, gaudy feathers. Nothing whole and fully formed.

Perhaps this piece of handiwork, which I approach without the faintest enthusiasm, can become just that.

B:209

209 p., bound; 36 x 23 cm + Supplement

Typewritten script. Director's script with handwritten diary notes. Supplement 1: Shooting schedule, 3 sheets.