Angels and Demons

Bergman's own private demons are legendary.

"I provide my own angels and demons."Sebastian in The Ritual (1969).

Angels and Demons

For many years, at least since the 1950s, Ingmar Bergman included a devil in his signature. Sometimes a diminutive and rather cute devil constituted the entire signature. But how come? A report on a Bergman film shoot in the magazine Filmjournalen in 1947 begins as follows:

Just over a week ago a young man with a distinctive terrier-like appearance stood on a barge in the Stockholm archipelago and cursed the weather 'powers' ]Strindberg's preferred term for his own 'demons']. He was dressed as he has been since he arrived in Stockholm a couple of months ago: in a pair of brown cord trousers, blue canvas shoes, an old sports shirt of indeterminate hue and, crowning it all a brown beret over his unkempt hair. Full of anger, yet with a wry smile of self irony, he clenched his fists and stared up into the grey skies: 'It must not rain! It must not rain!'

Curiously enough, it did start to rain. It's hard to say who was the most surprised; the director Ingmar Bergman or the actors around him. Torment-Ingmar or The Devil's-Bergman as he's also known in more intimate circles is usually looked upon favourably by the 'powers' after a couple of successful Strindberg productions, and it is seldom that anyone feels like answering him back, or otherwise contradicting him, when he settles down for a shoot.

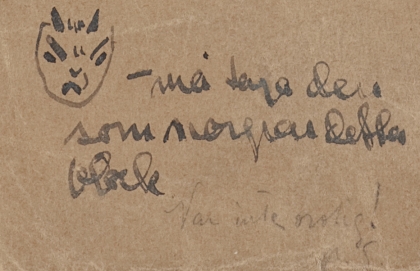

"– takes he who steals this notebook." Detail of Notebook no. 48.

Photo: Jens Gustafsson. © Ingmar Bergman Foundation.

The epithet "demon director" was something Bergman acquired at an early stage in his career, and one that has stuck. A 2004 article in the New Yorker magazine noted: "He long ago earned the nickname of the 'demon director', such are the demands that he makes on his performers." Bergman has himself admitted that his early attempts as a filmmaker could be somewhat demonic. When his first screenplay Torment was due to be filmed by Alf Sjöberg, Bergman served as assistant director. For the final takes he was allowed to assume the role of director: "I was told to shoot these last exterior, since Sjöberg was otherwise enganged. They were my first professionally filmed images. I was more exited than I can describe. The small film crew threatened to walk off the set and go home. I screamed and swore so laudly that people woke up and looked out their windows, it was four o'clock in the morning."

An article written in 1960 under the heading "Stop talking about my demonism, says Ingmar Bergman", begins with what is probably a fairly accurate description of the prevalent image of him at the time:

We have heard of the animal tamer, his jowls dripping with sadism, whipping his trembling performers into feats way above the ordinary. We have heard rumours of the demon director squeezing the last drops of life blood from his young players, violating them spiritually. We have heard about the ruthless egomaniac who stops at nothing to achieve his goals.

Bergman and Pernilla Allwin (as Fanny Ekdahl) during shooting of Fanny and Alexander (1982).

Photo: Arne Carlsson. © AB Svensk Filmindustri.

But as the article was quick to reveal, the image of Bergman as a demon director is hardly fair. There may have been something in it in his early period, but he is a long way from sharing Alfred Hitchcock's view that actors should be "treated like cattle". Quite the contrary: his actors and other colleagues never seem to tire of bearing witness to the warmth, trust and consideration he exuded during film shoots or stage rehearsals. This doesn't necessarily mean that he would have been unexceptionally kind-hearted: only that he knew better than trying to scare a good performance out of his collaborators. perhaps this aspect of Bergman's directorial philosophy is best summarised by a few lines from After the Rehearsal:

Anna Egerman: Many directors' paths are lined with crushed actors. Have you ever counted your victims?

Henrik Vogler: I love actors, so I can't hurt them.

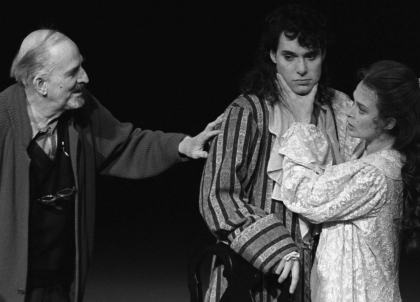

Bergman, Torsten Flinck and Lena Endre during rehearsal of The Misanthrope (1995).

Photo: Bengt Wanselius.

However, one should perhaps add that these eulogies to Bergman as a mentor are sung loudest by those who have not fallen on the wrong side of him. One example of the opposite, well known to readers of the gossip columns, occurred when his 1995 Royal Dramatic Theatre production of The Misanthrope was due to tour the USA. The leading role of Alceste was played by Thorsten Flinck, whose talent, according to Bergman, was virtually without equal. As an actor, and not least director, Flinck was already known as the bad boy of Swedish theatre. Apart from his much-discussed drug abuse, Flinck's public image was strikingly similar to that of Bergman's himself some fifty years previously: a self-consuming genius who makes enormous demands on himself and everyone around him. It is not hard to see how Bergman recognised himself in his young protégé. Yet mutual respect that spills over into identification is often the prelude to a break-up, and that is precisely what happened

The Misanthrope had received unanimously positive reviews, yet shortly before the planned tour to New York, Bergman saw the production once more, for the first time since the premiere. He did not, to put it bluntly, like what he saw. Flinck, he would later claim, had abandoned the direction he had received - and which he had stuck with at least until after the premiere – and in Bergman's words had "staged his own show". Bergman managed to get the Royal Dramatic Theatre to cancel the tour, and his public criticism of Flinck ensured that the break between the two of them became absolute.

Nonetheless the case of Flinck is an exception. Whether others have either stayed loyal regardless of any demonic outbursts from their director, or whether they have never experienced them, we may never know. Yet one fact remains: anyone who has ever worked with Bergman has found the experience unforgettable.

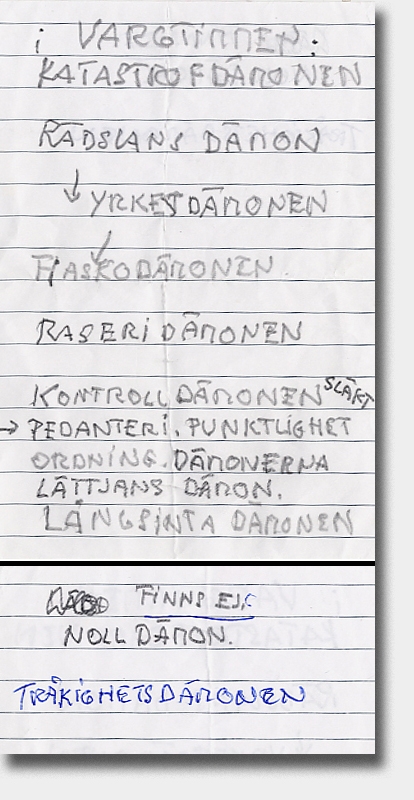

'Demon of disaster', 'demon of fear', 'profession demon', etc. List of demons as summarised by Bergman in Marie Nyreröd's documentary Bergman's Island (SVT, 2003)

© Marie Nyreröd

Demon or not, Ingmar Bergman's universe certainly has its fair share of demons. He constantly referred to his own demons, which other people might call neuroses or anguish attacks. This notion of metaphysical forces preying on the artist's psyche may perhaps be partly inspired by Bergman's idol August Strindberg, who called his own demons "the powers". Compare, for example, the following two quotations, the first from Bergman in The Magic Lantern, about a stay in hospital:

We were a meek collention of drugged zombies following an undemanding daily routine without protest. I was given five blue Valiums a day and two Mogadons at night. I felt in the slightest uneasy, I went at once to the nurse and was given an extra dose. I slept heavily and dreamlessy at night and dozed off for several hours a day.

And Strindberg in Inferno (1897):

In order to investigate the borderland between life and death I lie down on bed, uncork the bottle of cyanide and let its deadly fumes fill the room. He is coming closer, the Reaper, so mild and seductive, but at the last moment someone always appears or something happens that cuts everything off; the waiter has an errand, a wasp flies in through the window. The powers refuse me this one and only happiness, and I bow to their will.

Like Strindberg, Bergman often managed to make good use of his demons, by "harnessing them to his chariot", as he often put it.

Sources

- Ingmar Bergman Archives

- Ingmar Bergman, The Magic Lantern.

- Anthony Lane, "Smorgasbord: An Ingmar Bergman retrospective", New Yorker, 14 juni, 2004.

- Henrik Sjögren, Lek och raseri: Ingmar Bergmans teater 1938-2002 (Carlssons Bokförlag, 2002).

- Markel, "Skeppet går till Indialand", Filmjournalen 29 (nr. 30, 1947).

- Birgitta Steene, Ingmar Bergman: A Guide to References and Resources (Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1987).

- August Strindberg, Inferno (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 1897).