Bergman's Legacy

In the short history of cinema, Bergman is one of those proverbial giants, with what seems to be particularly broad shoulders to stand on.

"I think we are the sum of what we have read, seen and experienced. I do not think artists are born from emptiness! I am a small stone of a tall building, I depend on each element of the building, next to, above, below."Ingmar Bergman

Essay

“Bergman has meant a lot to me”, confessed Nuri Bilge Ceylan, interviewed by Le Monde about Winter Sleep, 2014 winner of the Palme d’Or. Others who would agree include Francis Ford Coppola, Terry Gilliam, Zhang Yimou, Martin Scorsese, Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu, Krzysztof Kieślowski, Woody Allen, Akira Kurosawa, Gus van Sant, Wes Anderson, Michael Haneke, Andrzej Wajda, Satyajit Ray, Richard Attenborough, Ettore Scola, Federico Fellini, Wes Craven, Ridley Scott, Park Chan Wok, Claire Denis, Ang Lee, Lars von Trier, Takeshi Kitano, the Dardenne brothers ...

Many filmmakers around the world have paid both written and oral tribute to Bergman. Discovering the Swedish director in the fifties and sixties, the authors of the French New Wave first published enthusiastic articles in the Cahiers du Cinéma. François Truffaut even quoted Summer with Monika in The 400 Blows (1959), testifying that Bergman’s work contributed to shaping his vocation for film.

The 400 Blows (François Truffaut, 1959).

More interestingly, Bergman's films have often been quoted, or even copied. Sequences of Wild Strawberries, for example, have been referred to by Woody Allen, David Cronenberg and Arnaud Desplechin; likewise, shots taken from Persona appear in David Lynch, Robert Altman or Stanley Kubrick’s films.

Tribute, criticism, parody, intentional reference or unconscious influence, sheer coincidence... Which 10 Bergman’s films have been the most influential and why? As was the Swedish director towards his own masters, his followers should be regarded as heirs rather than copycats. Their films testify to the topicality of Bergman’s legacy. This essay, based on hypotheses and far from being exhaustive, aims at being enriched by further contributions.

1. Summer with Monika – A cinematic revolution

The French first discovered Bergman’s work through Summer with Monika, in 1954. “Swedish” meaning “erotic” at that time, the film was launched in a network of semi-pornographic cinemas. Its outdoor shoots and its outspokenness made a strong impression on the young writers of the Cahiers du Cinéma, who saw in it the emergence of a new aesthetic. In The 400 Blows (1959), François Truffaut thus paid tribute to the film, having Antoine Doinel and his playmate steal a very suggestive picture of Harriet Andersson at the front of a movie theater.

What struck these young filmmakers was not only the outdoors shooting and the naked body of Harriet Andersson, but also the effect of detachment, particularly at the end of the film, when the camera stops on a weary Monika.

What were we dreaming of when Summer with Monika was first shown in Paris? Ingmar Bergman was already doing what we are still blaming French directors for not doing. […] And that last shot of Nights of Cabiria, when Giulietta Masina stares fixedly into the camera: have we forgotten that this, too, appeared in the last reel but one of Summer with Monika? Have we forgotten that we had already experienced – but with a thousand times more force and poetry – that sudden conspiracy between actor and spectator [...], when Harriet Andersson, laughing eyes clouded with confusion and riveted on the camera, calls on us to witness her disgust in choosing hell instead of heaven?”

(Jean-Luc Godard, Cahiers du Cinéma, July 1958)

Harriet Andersson in Summer with Monika (1953).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Giulietta Massina in Nights of Cabiria (Federico Fellini, 1957).

Apart from his affirmations in writing, Godard also made tribute to the famous last shot of Summer with Monika in his films: both Breathless (1959) and To Live One's Life (1962) end with their respective female lead looking directly into the camera (as well as by having Jean-Paul Belmondo directly addressing the audience in the former).

Harriet Andersson in Summer with Monika (1953).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Anna Karina in To Live One's Life (Jean-Luc Godard, 1962).

When interviewed on this subject, Bergman revealed his own sources:

Do you know where it has always existed? In the theatre. When actors address the audience directly and comment on the action. I resorted to this method myself in Summer with Monika. […] At that time, it was strictly prohibited.”

(Bergman on Bergman)

Summer with Monika’s cinematic revolution would thus come from an old theatrical device! Indeed, the year it was released, Bergman directed Pirandello's play Six Characters in Search of an Author, based on the same paradigm. Bergman, who directed The Three-Penny Opera in 1950, may also have had in mind Brecht's theory about Verfremdung – the distancing effect – except that Monika’s look aimed at arousing emotion, whereas Brecht’s intention was to preserve the spectator’s analytical detachment.

A great admirer of Alfred Hitchcock, Bergman may finally have been inspired by Shadow of a Doubt, released ten yers earlier than Summer with Monika. Looking right into the camera, Joseph Cotten (as murderer Charles Oakley), seems to defy the viewer to judge him.

Joseph Cotten in Shadow of a Doubt (Alfred Hitchcock, 1943).

At any rate, the shock wave of Summer with Monika’s last shot seems to have spread across Europe and the world, until today.

Harriet Andersson in Summer with Monika (1953).

Uma Thurman in Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994).

Other looks directed towards the camera can be found in Winter Light and Saraband, when, respectively, Märta's and Marianne's letters are read frontally, as if addressed to the viewer. These shots may have inspired similar sequences in Arnaud Desplechin’s Esther Kahn (2000) and A Christmas Tale (2008). The French filmmaker makes no secret of his admiration for Bergman, about whom he once said: “While making a film, he is the only one whom I forbid myself to think of, otherwise I would stop everything”.

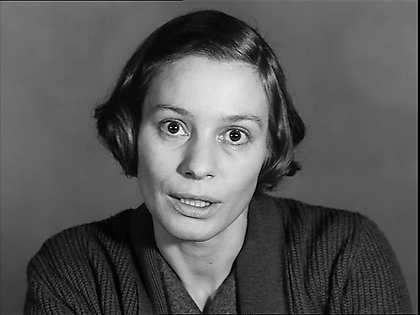

Ingrid Thulin in Winter Light (1963).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

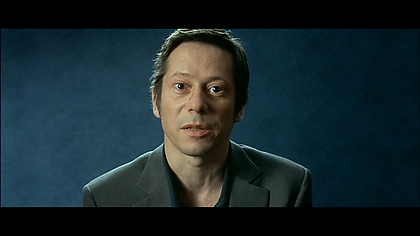

Mathieu Amalric in A Christmas Tale (Arnaud Desplechin, 2008).

Likewise, at the beginning of A Christmas Tale, Juno's keynote speech is reminiscent of Marianne’s address to the audience in the opening of Saraband, which Desplechin had just seen before he began to write his own film.

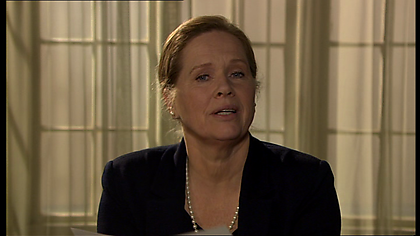

Liv Ullmann in Saraband (2003).

© Sveriges Television / AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Catherine Deneuve in A Christmas Tale (Arnaud Desplechin, 2008).

2. Smiles of a Summer Night – First international success

The first of Bergman's films to bring the director international success, due to its exposure at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, was inspired by Marivaux’s comedies and Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and it inspired, in turn, both Stephen Sondheim’s musical A Little Night Music (1973) and Woody Allen’s A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982). It is far from being the only allusion to the Swedish master in Allen’s work. The American director referred to Bergman as "probably the greatest film artist since the invention of the motion picture camera (Chaplin, 1988) and admired “this combination of intellectual artist and film technician”. (Time, 2007) Allen subsequently worked with two of Bergman’s collaborators – Sven Nykvist on four films (Another woman, 1987; Crimes and Misdemeanors, 1989; New York Stories, 1989; Celebrity, 1998), and Max von Sydow, who played the part of the tormented artist in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), as an implied reference to his roles in The Magician and Hour of the Wolf.

Smiles of a Summer Night (1955)

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy (Woody Allen, 1982).

In a nod to Sawdust and Tinsel (1953), the character played by Woody Allen in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) wants to commit suicide at the end, but due to perspiration, the gun slips and the ball hits a mirror instead of him. As in Bergman’s film, an insistent ticking is heard during the whole scene.

3. The Seventh Seal – An iconic encounter with Death

Bergman's most famous film takes much of its imagery from medieval art. Thus, the vision of a man playing chess with Death was inspired by Albertus Pictor’s paintings. However, here again, remember that Bergman was first and foremost a man of the theatre. Just prior to shooting, he directed, as a radio play, Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Everyman, whose main theme is – an encounter with Death. The opening scene became a source of inspiration for many film-makers, such as David Lynch.

In Lost Highway as in The Seventh Seal, Death is dressed in black, whiteface; when he first appears, among the guests at a party, the room falls silent. The question asked by this “Mystery Man” in Lynch’s film – "We have already met, haven't we?" – echoes Death's first words to the Knight in Bergman’s film: “I´ve already been with you for a long time”. However, Death in Lost Highway has a demonic aspect and mocking smile, whereas in The Seventh Seal, he is “neutral” and seems to take no pleasure in killing.

John Boorman and Terry Gilliam have acknowledged the influence of The Seventh Seal on their work, and Paul Verhoeven has remarked: "It made me realize that films can be art. It inspired me to become a film director. This is one of the most powerful and significant films ever made."

This iconic film has been the subject of numerous pastiches and parodies, among them Woton’s Wake, Brian de Palma’s student movie, full of filmic allusions from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to The Seventh Seal.

As for Woody Allen, he has referenced the film in two of his own, Love and Death and Deconstructing Harry. In a 1988 New York Times interview, he stated that “The finale, as Death dances off with all the doomed people to the nether lands, is one of the most memorable shots in all movies".

Love and Death (Woody Allen, 1975).

4. Wild Strawberries – Breaking time/space film conventions

Two sequences of Wild Strawberries are frequently quoted: 1) the first nightmare, during which Isak Borg dreams he is lost in a sunny empty street, and, after a look at a clock without hands, finally meets a man, who collapses; 2) the family lunch scene, as remembered by old Isak many years later. Both scenes seem influenced by August Strindberg, whose introduction to A Dream Play might be the credo of Wild Strawberries (it will later be openly quoted in Fanny and Alexander):

Time and space do not exist. Upon an insignificant background of real life events, the imagination spins and weaves new patterns; a blend of memories, experiences, pure inventions, absurdities and improvisations.

Given that during the five years prior to Wild Strawberries Bergman produced no fewer than three Strindberg plays (The Crown Bride, Ghost Sonata, Erik XIV) the affinities are hardly surprising.

1. Nightmare Scene

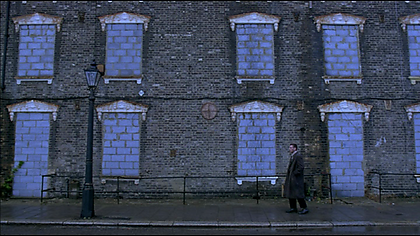

In the beginning of David Cronenberg's Spider, Dennis Cleg (Ralph Fiennes) roams a derelict urban area reminiscent of Isaac’s opening nightmare:

Victor Sjöström in Wild Strawberries (1957).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Ralph Fiennes in Spider (David Cronenberg, 2002).

Victor Sjöström in Wild Strawberries (1957).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Ralph Fiennes in Spider (David Cronenberg, 2002).

In the nightmare sequence of Desplechin's Esther Kahn, Esther dreams of a sunny, deserted street, whose doors and windows are all closed. She meets a faceless man, who suddenly collapses. Later in the movie, Esther, like Isak in Wild Strawberries, is said to be "dead, hard and cold".

Wild Strawberries (1957).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Esther Kahn (Arnaud Desplechin, 2000).

Wild Strawberries (1957).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Esther Kahn (Arnaud Desplechin, 2000).

Wild Strawberries (1957).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Esther Kahn (Arnaud Desplechin, 2000).

2. Family Lunch Scene

In this episode, the elderly Isak remembers a family lunch which took place in the past, while remaining on the doorstep of the dining-room. This scene, where Bergman made past and present coexist on screen, has been quoted by Woody Allen (in Another Woman, 1988 and Crimes and Misdemeanors, 1989), Arnaud Desplechin and David Cronenberg.

Wild Strawberries (1957).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Crimes and Misdemeanors (Woody Allen, 1989).

Wild Strawberries (1957).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

My Sex Life ... or How I got Into an Argument (Arnaud Desplechin, 1996).

Wild Strawberries (1957).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Spider (David Cronenberg, 2002).

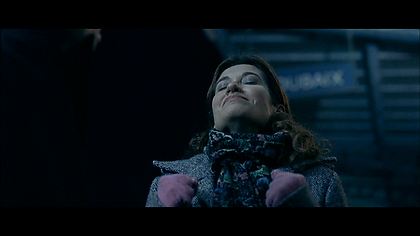

5. The Virgin Spring – Remakes

Since Andrei Tarkovsky stated that he was "only interested in the views of two people: one is called Bresson, the other is called Bergman" (Sculpting in Time, 1989), the fact that his last film was shot in Sweden with several members of Bergman's team, including Sven Nykvist, Allan Edwall and Erland Josephson, was hardly surprising. Tarkovsky originally wanted to shoot the movie on Fårö, where Through a Glass Darkly, Persona, Shame, The Passion of Anna had been shot, but he eventually had to settle for Närsholmen south of Ljugarn on the adjacent island of Gotland. In The Sacrifice, Tarkovsky quotes the scene where Max von Sydow is struggling with a birch in The Virgin Spring:

The Virgin Spring (1960).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Sacrifice (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1986).

A somewhat surprising remake of The Virgin Spring is Wes Craven's classic horror movie The Last House on the Left (which in turn has been remade with the same title by Dennis Iliadis in 2009).

Tor Isedal and Birgitta Pettersson in The Virgin Spring (1960).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

David Hess and Sandra Cassell in The Last House on the Left (Wes Craven, 1972).

6. The Silence – Loneliness

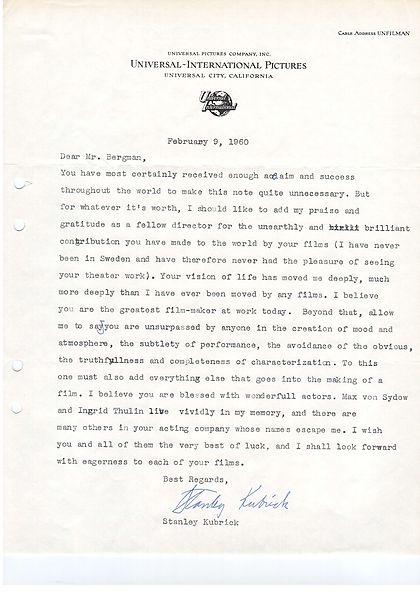

In February 1960, Stanley Kubrick wrote a letter to Bergman:

“Your vision of life has moved me deeply, much more deeply than I have ever been moved by any films. I believe you are the greatest film-maker at work today […], unsurpassed by anyone in the creation of mood and atmosphere, the subtlety of performance, the avoidance of the obvious, the truthfulness and completeness of characterization. To this one must also add everything else that goes into the making of a film; […] and I shall look forward with eagerness to each of your films.” (Letter from Ingmar Bergman to Stanley Kubrick, dated February 9, 1960, K:636 in the Ingmar Bergman Archives.)

To claim, then, that Kubrick might have been inspired by The Silence for the scenes of his young hero roaming the hotel corridors in The Shining (1980), does not seem too much of a stretch.

The Silence (1963).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980).

Besides, another scene in The Shining reminds us of a shot in the prologue of Persona:

Persona (1966).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980).

It seems that it was a mutual admiration. In July 1981, according to his diary, Bergman saw The Shining. Fanny and Alexander was broadcast on Swedish TV in December 1982. There are similarities with Kubrick’s masterpiece, especially the two dead girls, who appear to young Alexander in the attic.

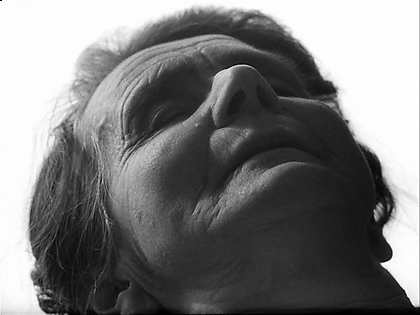

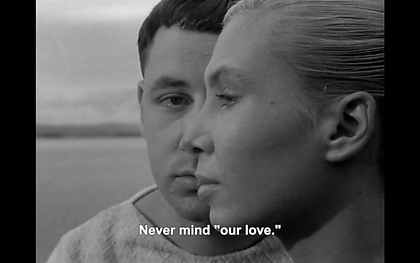

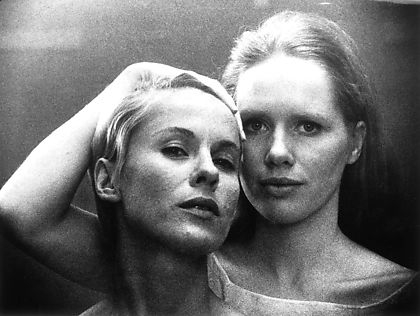

Juxtaposed faces

The Silence marks a kind of culmination of what could be called a signature of Bergman: juxtaposed faces, as to illustrate the fact that the characters are unable to look at or to talk to each other. It conveys a feeling of loneliness and incommunicability. This shot, which first appeared in Thirst, has often been referred to by other filmmakers, such as Agnès Varda, John Cassavetes and Alain Resnais, or, more recently, David Mackenzie and David Fincher.

Hasse Ekman and Birgit Tengroth in Thirst (1949).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Philippe Noiret and Silvia Monfort in La pointe courte (Agnès Varda, 1955).

Delphine Seyrig and Giorgio Albertazzi in Last Year in Marienbad (Alain Resnais, 1961).

Max von Sydow and Ingrid Thulin in The Magician (1958).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Anthony Ray and Lelia Goldoni in Shadows (John Cassavetes, 1959).

Gunnel Lindblom and Ingrid Thulin in The Silence (1963).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Rosamund Pike and Ben Affleck in Gone Girl (David Fincher, 2014).

Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson in Persona (1966).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Sophie Marceau and Monica Bellucci in Ne te retourne pas (Marina de Van, 2009).

Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann in Shame (1968).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Eva Green and Ewan McGregor in Perfect Sense (David Mackenzie, 2011).

Erland Josephson and Max von Sydow in The Passion of Anna (1969).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Pascal Greggory and Julie Depardieu in Le mariage à trois (Jacques Doillon, 2010).

These images are so ingrained in our culture that they are readily recognizable (and, as such, the subject of numerous parodies).

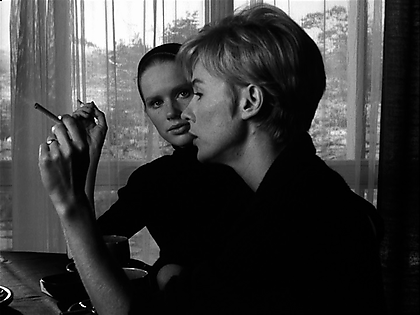

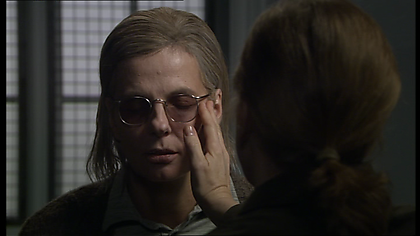

7. Persona – Theme of the Double

Yet again borrowing from Strindberg (The Stronger, an 1889 play), the theme of Persona recurs in numerous successive variations. Les Biches, a 1968 French film directed by Claude Chabrol, depicts a tortured lesbian relationship between two women resting in a villa. In Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, Betty and Rita begin to share and swap personality traits. Finally, 3 Women (Robert Altman, 1977), depicts the increasingly bizarre, mysterious relationship between a woman and her roommate, going as far as to exchanging their relative status. Robert Altman once stated: “Everything I've learned has come from watching other directors: Bergman, Fellini, Kurosawa, Huston and Renoir.” A masculine version of this “double” face picture can be found in John Woo’s Face/ Off (1997), in which a cop and a criminal exchange faces.

Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann in Persona (1966).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Jacqueline Sassard and Stéphane Audran in Les biches (Claude Chabrol, 1968).

Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann in Persona (1966).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Laura Harring and Naomi Watts in Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001).

Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann in Persona (1966).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Laura Harring and Naomi Watts in Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001).

Bibi Andersson/Liv Ullmann in Persona (1966).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Shelley Duvall/Sissy Spacek in 3 Women (Robert Altman, 1977).

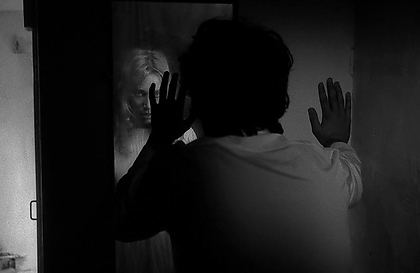

On Cinema

At the end of the sixties, Bergman increasingly resorted to self-reflexive devices, notably film-within-a-film at the beginning of Persona and Hour of the Wolf, or interviews with the actors on their character in The Passion of Anna. The most famous sequences probably remain Persona’s prologue and epilogue – where a boy, touching the split-screen image of a moving face, calls the viewers’ attention to the motion picture apparatus. This shot from Persona has been quoted by – among others – Jean-Luc Godard in his Histoire(s) du cinéma (1999), Philippe Garrel in Frontier of Dawn (2008) and Desplechin, towards the end of A Christmas Tale (2008), when Henri puts his hand on the hospital transparent curtain that separates him from his impassive mother.

Persona (1966).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Histoire(s) du cinéma (Jean-Luc Godard, 1999).

Frontier of Dawn (Philippe Garrel, 2008).

A Christmas Tale (Arnaud Desplechin, 2008).

This famous shot may in turn have been taken by Bergman from Jean Cocteau's 1950 Orphée, described by Bergman in 1959 as “one of the most beautiful French films of all-time”.

Jean Marais in Orphée (Jean Cocteau, 1950).

Jörgen Lindström in Persona (1966).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

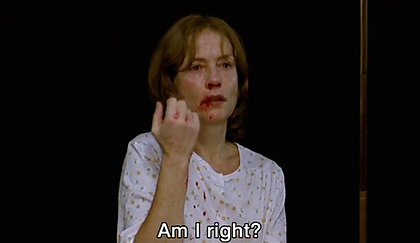

8. Cries and Whispers – Interiors

While Cries and Whispers may have inspired the theme and tone of Woody Allen's Interiors (1978), it has probably also influenced Another woman ten years later, through the figure of the Mother, coming from the garden in a white dress, as an elegant ghost from the past.

Cries and Whispers (1973).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Another Woman (Woody Allen, 1987).

More violent is Karin's vaginal mutilation in the middle of the film, which seems to have made some impression on Michael Haneke and – in a different register – William Friedkin.

Ingrid Thulin in Cries and Whispers (1973).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Isabelle Huppert in The Piano Teacher (Michael Haneke, 2001).

Cries and Whispers (1973).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973).

The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973).

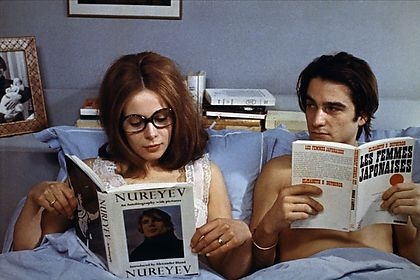

9. Scenes from a Marriage – Masculine-Feminine

Bergman once admitted: “I did like Truffaut enormously, I esteemed him, in fact. His way of relating with an audience, of telling a story, is both fascinating and tremendously appealing. […] I can see some of Truffaut’s films again and again without growing tired of them”. Indeed, there are some similarities between Scenes from a Marriage and Truffaut’s Domicile conjugal (Bed and Board), which had been released a few years earlier:

Claude Jade and Jean-Pierre Léaud in Bed and Board (François Truffaut, 1970).

Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann in Scenes from a Marriage (1973).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Some shots of Rob Reiner’s When Harry Met Sally (1989) are reminiscent of Scenes from a Marriage. More recently, Asghar Farhadi may have unconsciously referred to Bergman's piece in A Separation. As a matter of fact, the Iranian director stated in a 2012 interview:

After I had completed the film, when I was watching it I suddenly realized that the placement of the camera in the first scene is extremely similar to the placement of the camera in Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage. Bergman is one of my favorite filmmakers and I think so very highly of his work.

Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan in When Harry Met Sally (Rob Reiner, 1989).

Peyman Moaadi and Leila Hatami in A Separation (Asghar Farhadi, 2011).

As for François Ozon, whose 5 x 2 (2005) also has a clear antecedent in Scenes from a Marriage, he simply stated: “Bergman is for eternity".

10. Fanny and Alexander – Religion vs occult powers

By his own admission, Arnaud Desplechin had Fanny and Alexander in mind when he wrote A Christmas Tale. The timing (Christmas festivities) and five acts editing (yet another theatrical device) probably are borrowed from Bergman’s film. One scene is particularly reminiscent of it: when Faunia (Emmanuelle Devos) prays for her friend Henri, she clenches her hands, while a surreal white light floods the screen, and a violin chromatic scale is heard. In a 2008 interview, Arnaud Desplechin told me he had felt it was the most effective way to shoot this particular scene.

Erland Josephson in Fanny and Alexander (1982).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Emmanuelle Devos in A Christmas Tale (Arnaud Desplechin, 2008).

Finally, Michael Haneke’s White Ribbon, winner of the 2009 Cannes Palme d’Or, is reminiscent of three Bergman films. As in The Passion of Anna, unexplained criminal acts – among which a barn burning down – occur in a small and quiet village and are related by a voice-over. Like Pastor Tomas Ericsson in Winter Light, the local doctor, a widower, humiliates his mistress. Like Bishop Edvard Vergerus in Fanny and Alexander, the local puritanical pastor gives his pubescent children a guilty conscience over apparently small transgressions.

There is also a seeming kinship between Bergman’s last opus Saraband and Haneke’s latest work, Amour.

Bertil Guve in Fanny and Alexander (1982).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Leonard Proxauf in The White Ribbon (Michael Haneke, 2009).

Gunnel Fred in Saraband (2003).

© Sveriges Television / AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Emmanuelle Riva in Amour (Michael Haneke, 2012).

Temporary Conclusions

Bergman's Legacy

Bergman’s work has influenced many filmmakers from all over the world, however different their styles may be. Both form and content are concerned. Thus, bergmanian themes of Memory, Marriage and Religion were respectively revisited by Allen, Farhadi or Haneke. More interestingly, Bergman initiated several formal revolutions that still appear as a source of inspiration to many directors:

- Monika’s look into the camera as referred to by Fellini, Godard, Tarantino;

- the break of time and space film conventions in Wild Strawberries inspired Allen, Cronenberg, Desplechin;

- shots of juxtaposed faces as in The Silence and Shame were copied by Resnais, Cassavetes, Fincher;

- shots from Persona melting down two feminine faces, were used again by Lynch, Chabrol, Altman.

Above all, Bergman made cinema “a medium of personal and introspective value”, according to the American screenwriter and director Paul Schrader, who sees there the reason why “he has left a legacy greater than any other director.

Bergman's Sources

On the one hand, theatre seems to have been an inexhaustible source of inspiration for Bergman. Thus, his work as a stage director, far from involving sterility in film form, enabled him to invent new cinematic devices. Strindberg’s chamber plays and daydream atmosphere (cf. the influence of A Dream Play on Wild Strawberries or that of The Stronger on Persona); Shakespeare's and Marivaux’s love intrigues (Smiles of a Summer Night); Hofmannstahl’s morality plays (The Seventh Seal); Pirandello’s resort to self-reflexive devices (Summer with Monika, The Passion of Anna); Chekhov’s picture of intimate relationships (Cries and Whispers) ... As Bergman once admitted: “There certainly would be a lot to say about the intimate relationship between my work in the theatre and my work in the cinema” (Bergman on Bergman).

On the other hand, Bergman also had a bulimic and omnivorous passion for film. Thus, Summer with Monika’s last shot is reminiscent of Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt ; Bergman himself considered The Virgin Spring a lousy imitation of Kurosawa; the prologue to Persona echoes Cocteau’s Orphée, while Scenes from a Marriage shares some similarities with Truffaut’s Domicile conjugal. Here again, the subject merits further studies ...

© Charlotte Renaud, 23 November, 2014

Källor

- Allen, Woody, “Through a Life Darkly”, The New York Times (September 18, 1988).

- Béranger Jean, Ingmar Bergman et ses films, Le Terrain vague, 1959 (about Cocteau’s Orphée).

- Bergman Ingmar, The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography, translated by Joan Tate (1988).

- Björkman Stig, Torsten Manns and Jonas Sima, Le Cinéma selon Bergman (Bergman on Bergman), Paris, Seghers, 1973.

- Cahiers du cinéma, May 2008 (Desplechin on Saraband).

- Chaplin, No. 215-216, 1988: Special Issue on Bergman for his 70th birthday (contributors: Kurosawa, Wajda, Fellini, S. Ray, Attenborough, Scola ...)

- Cardullo Bert, Soundings on Cinema, An interview with Ingmar Bergman, 2008, State University of New York, (on Truffaut p. 205).

- Corliss, Richard, “Woody Allen on Ingmar Bergman”, Time, August 1, 2007.

- Filmkonst (December 18, 2007): 49 x Bergman (Allen, Lee, Pen-Ek Ratanaruang …)

- Gado Frank, The Passion of Ingmar Bergman, Durham, North Carolina, 1986.

- Godard, Jean-Luc, “Bergmanorama”, Cahiers du cinéma, July 1958.

- Oliver Roger W. (ed.), Ingmar Bergman, Film, Theater, Books, Ed Gremese, 1999 (Allen, Truffaut, Godard).

- Sydsvenskan (May 12, 2002): “När Bergman går på bio”, interview by Jan Aghed (about Masculine-Feminine).

- Tarkovsky Andrei, Sculpting in Time, Paperback, 1989.

- Télérama (December 15, 2004): on Sarabande (Assayas, Chéreau, Jacquot and Desplechin).

- Timm Mikael, Lusten och dämonerna, Stockholm, Norstedts, 2008.

- The Wall Street Journal (January 6, 2012): interview with Asghar Farhadi

- Trespassing Bergman, Sweden 2013, 6 x 45 min/ A Gädda Five Production by Hynek Pallas, Jane Magnusson, Fatima Varhos

- Quotes from Fellini, Altman, Schrader, Lee, Ray, Scorsese, http://www.criterion.com/lists/178298-directors-talk-directors

- Quote from Kubrick : http://www.vulture.com/2011/07/read_stanley_kubricks_fan_lett.html