A Matter of Death and Life: the Films of Ingmar Bergman

Geoff Andrew, filmskribent känd från Sight & Sound och mångårig medarbetare på BFI i London, ger en personlig introduktion till Bergman.

By Geoff Andrew

”Here, at last, was a filmmaker whose readiness to confront the ‘big questions’ made him the equal of those towering figures working in other, more widely respected artforms: novelists, poets and playwrights, composers, painters and sculptors.”

When they hear or see the words Ingmar Bergman, most people – if, of course, they recognise the name at all – probably think of a gloomy Swede obsessed with human suffering, angst and mortality. There might also spring to mind an image of a medieval knight on a sea shore playing a game of chess with Death - or at least with a white-faced man in a black hood and cloak. Such pigeon-holing is perhaps inevitable, given that The Seventh Seal (1957) is not only one of Bergman’s most famous films but has been much mimicked, mocked and referenced: it even featured in Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey (1991).

But one should always be wary of stereotypes. Bergman’s enormous contribution to the arts – besides the many works he wrote and directed for the cinema and television, he consistently maintained a hugely successful and influential parallel career in the theatre – is considerably more varied than any miserabilist caricature might suggest. Furthermore, for all its iconic notoriety, The Seventh Seal is atypical; though Bergman did set a handful of his stories in the past, most of his films had contemporary settings, and he generally steered well clear of allegory. Indeed, though it has its good points, Bergman’s best known film is far from his best film, and those unfamiliar with his work who would like to find out what the fuss is all about would do well to begin by exploring elsewhere.

While it would be absurd and misleading to downplay Bergman’s interest in the more painful and problematic aspects of everyday existence (at least as it is experienced by those for the most part unaffected by economic hardship in the affluent West), it is important to emphasise the fact that his films are not in themselves ‘depressing’.

True, many of them deal with characters undergoing some kind of crisis, and do so in a way which is often remarkable for its unflinching honesty. (Few if any filmmakers have been so adept at depicting the subtle but savage acts of verbal and mental cruelty humans can inflict on one another.) Yet Bergman’s cinematic and dramaturgical skill is such that one is often utterly engrossed in a film from beginning to end, and emerges from it invigorated by his artistry, exhilarated by his audacity, and strangely heartened by his keen, compassionate understanding of what it means to be alive.

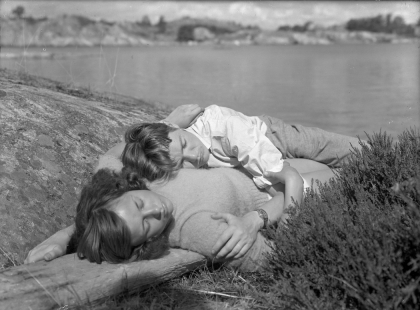

Of course, over a career that spanned more than half a century, Bergman’s achievements were uneven, and certainly his earliest films as a director feel like apprentice works compared to the extraordinary achievements of the late 50s and thereafter. Nevertheless, those immature works reveal a rapidly developing talent of no little intelligence, ambition or promise. Even the first of his scripts made into a film – Torment (1944), directed by Alf Sjöberg – is notable for its astute grasp of the dark, sadomasochistic undercurrents that may shape human relationships. As for his own directorial efforts, after a number of films displaying the influence of Italian neorealism, around the start of the 1950s he began to reveal his own distinctive sensibility with impressive works like Thirst (1950), Summer Interlude (1951), Summer with Monika (1953) and Journey Into Autumn (1955).

What distinguishes these films – apart from their very fine acting and the atmospheric cinematography of regular collaborator Gunnar Fischer – is a fascination with the seemingly inevitable tensions that arise in male-female relationships: tensions emanating, usually, from the conflict between a woman’s need and desire for a properly fulfilling life and a man’s inability or reluctance – due to pride, vanity, short-sightedness or whatever – to respond sympathetically to that need and desire. While it would be misleading to characterise these and subsequent films as ‘feminist’, it is nevertheless true that Bergman, throughout his career, not only made an unusually large number of films focused primarily on the point of view of a woman, but portrayed his male characters in a somewhat less positive light than their female counterparts.

It was with the prize-winning triple-whammy of Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) – a delightfully spiky comedy of marital manners – The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries (1957) – a road-movie in which an elderly academic takes stock of his life, and arguably Bergman’s warmest film – that Bergman established his international reputation as the world’s leading arthouse auteur. Here, at last, was a filmmaker whose readiness to confront the ‘big questions’ made him the equal of those towering figures working in other, more widely respected artforms: novelists, poets and playwrights, composers, painters and sculptors. In creating works that examined how we live with ourselves and one another, where the world is going, whether God exists, how to find happiness, and so forth, Bergman once and for all demolished any notion that film could and should only be about escapist entertainment. Undoubtedly, this was no industry hack; this was an artist.

Yet his very finest works were still to come. With the loose ‘trilogy’ of Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1962) and The Silence (1963), Bergman forged a new style for himself, that would endure more or less unchanged until Saraband (2003), made at the end of his career. Visually, with his new regular cinematographer Sven Nykvist, he created a crisper, simpler, more sharply focused look consisting largely of stark, uncluttered compositions and facial close-ups.

This was mirrored, in narrative terms, by a shift to stories involving fewer individuals – they were, he said, essentially chamberworks – from which all superfluous detail had been pared away. Without needless delay, we are quickly plunged, as if into an icy pool, into the heart of the matter, whatever that may entail: in the trilogy, a family faced with the swiftly declining sanity of one of its members; a priest undergoing a loss of faith; the relationship of two sisters ravaged by resentment and illness. The camera’s unblinking gaze, the fearless performances, the attention to the Aristotelian unities of action, time and place, and the taut narrative economy all make for bracingly intense viewing.

There followed many masterworks, most memorably, perhaps, the extraordinary Persona (1966), in which an actress, struck dumb by her sudden recognition of the cruel horrors of the modern world, becomes involved in a strangely symbiotic relationship with the talkative nurse assigned to oversee her convalescence.

This began a series of marvellously inventive, incisive and insightful studies in fragile human psychology and fraught interaction, works whose elegant formal qualities were always at the service of content and meaning. The nightmarish images of Hour of the Wolf (1968) bring to vivid life the mental turmoil of a painter (many of Bergman’s films centre, somewhat self-reflexively, on creative figures of one kind or another); the sombre red walls and furnishings that surround the sisters in Cries and Whispers (1972) – one of the great films about death – were in line with Bergman’s notions of the colour of the interior of the human soul; and the forthright, up-close-and-personal visual style then prevalent in television was the perfect medium for the illuminatingly intimate look at marital strife and breakdown in Scenes from a Marriage (1973), and for the likewise brilliant account of familial tensions in Fanny and Alexander (1983).

Thereafter, Bergman concentrated largely on theatre, occasional television films, and scripts he wrote for others to direct; the best known were for Best Intentions (1992), directed by Bille August, and Faithless (2001), directed by Liv Ullmann, his one-time partner and the lead actress in many of his masterworks of the 60s and 70s. (Bergman worked regularly with a repertory group of grade-A actors – including Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, Gunnel Lindblom, Gunnar Björnstrand, Max von Sydow and Erland Josephson – and was repeatedly rewarded with performances of amazing subtlety and power.) But as his memorably dark swansong Saraband displayed, both his courage and his genius remained magnificently undimmed. The film may have been his final screen credit as writer-director, but with its frighteningly frank account of pride, vanity, cruelty, guilt, frailty and fear, it was one more reminder that Bergman was – and always had been – a filmmaker quite unlike any other. In returning, over and over, to his favourite subject – the individual human psyche, in all its mysterious complexity – he had taken inspiration not from other movies, but from life. And that life had been his own.

This piece – an introduction to the work of Ingmar Bergman – was written for the website of the Tyneside Cinema, Newcastle, which in November 2017 mounted a brief season of his films.

Geoff Andrew is a film critic, programmer and lecturer. He has written and contributed to numerous books on the cinema, and curated the forthcoming Bergman retrospective at London's BFI Southbank. He currently writes on film, music and the arts at geoffandrew.com