Summer with Monika

A young couple fall in love, escape from the city and spend the summer in the Stockholm archipelago.

"Summer with Monika is the most original film of the most original of directors."Jean-Luc Godard

About the film

1952 was one of Ingmar Bergman's most productive years, probably because he had such a backlog of creative ideas: the previous year he had been prevented from making features when Sweden's film producers had staged a lockout in protest against the high rate of tax on entertainment. To make ends meet he turned to advertising, making nine films to promote the Bris deodorant soap brand for Swedish Unilever ('kills bacteria – no bacteria – no smells').

Bergman in Images: My Life in Film:

Originally, I accepted the Bris commercials in order to save the lives of myself and my families. But that was really secondary. The primary reason I wanted to make the commercials was that I was given free rein with money and could do exactly what I wanted with the product's message. Anyhow, I have always found it difficult to feel resentment when industry comes rushing toward culture, check in hand. My whole cinematic career has been sponsored by private capital. I have never been able to live on my beautiful eyes alone! As an employer, capitalism is brutally honest and rather generous when it deems it beneficial. Never do you doubt your day-to-day value a useful experience which will toughen you.

Once the conflict between the film industry and the Swedish state had ended, Bergman found himself with plenty to do. Between January and April he directed four plays for Swedish Radio Theatre, and put on his own Murder at Barjärna at the Malmö Municipal Theatre (where he was employed at the time as permanent director). Another one of his own plays, The Day Ends Early, was broadcast by Radioteatern under the direction of Bengt Ekerot. He then made two feature films: Waiting Women, shot between April and June, and Summer with Monika from July to October.

Following his international breakthrough at the end of the 1950s, Bergman gained a reputation as the portrayer of the upper echelons of society par excellence. His characters were often artists and intellectuals, all firmly rooted in the upper middle classes. It is no coincidence that he happened to originate from such a background himself, so it may come as some surprise to those more familiar with films such as Smiles of a Summer Night, Wild Strawberries and Fanny and Alexander to learn that his earlier works often featured principal characters from the working classes. Summer with Monika is based on a short story by Per Anders Fogelström which he subsequently adapted into a novel. One of Sweden's most popular authors, Fogelström was best known for his portrayals of working class life in Stockholm. His most celebrated works include a series of novels about Stockholm, beginning with City of My Dreams (Mina drömmars stad, 1960) and ending with City in the World (Stad i världen, 1968).

Bergman and Fogelström had worked together previously on the screenplay of Fogelström's While the City Sleeps. In an interview Bergman tells the story of how they bumped into each other again by chance on Kungsgatan in central Stockholm:

I asked him what he was doing. He said: 'I've got a thing in my head, but how it's going to turn out I dont know. 'Really?' 'Yes, it's about a girl and a fellow, just kids, who pack their jobs and families and beat it out into the archipelago. And then come back to town and try to set up in some sort of a bourgeois existence. But everything goes to hell for them.'

I remember jumping a yard high into the air and saying: 'We're going to make a film of this! Remember 'we're going to make a film of this!' He thought so, too; but then other things came between. But each time we met, I asked him how things had turned out for that couple. And by and by, during the film stoppage I suppose it must have been, we got down to work on the script.

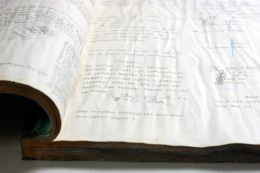

We cannot be sure of the precise details of their collaboration, but from the material still available it appears that Fogelström wrote a draft screenplay that was subsequently developed either by both of them, or by Bergman working alone. As Fogelström remembers well, the focus in the film version shifted from Harry to Monika.

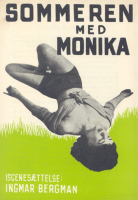

Given that the film is to such a large extent told from Monika's point of view, the title, which is carried over from the novel, is somewhat odd: for surely 'Summer with Monika' implies that the man's story is being told? In all probability SF (and perhaps Bergman himself) wanted to keep the novel as intact as possible: Fogelström was popular, and marketing material for the film prominently featured his name.

Bergman and Fogelström's screenplay was passed on to Carl Anders Dymling at SF with the promise that it would be 'very small and simple – the world's cheapest film.' After the break in film production of the previous year, the company needed all the films it could get, and despite or perhaps because of the erotic elements in the script, it was accepted. Later, Bergman would claim that a member of the board resigned in protest at such filth.

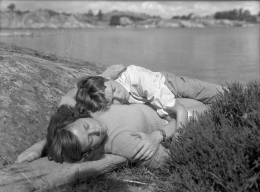

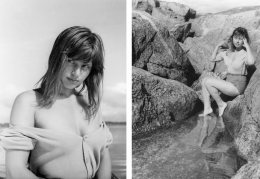

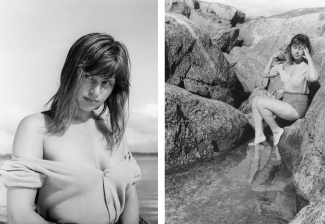

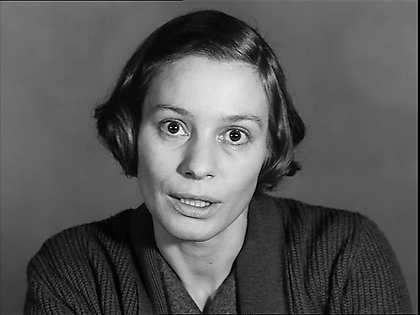

The role of Monika went to Harriet Andersson, a young actress with a few minor roles to her credit, including a part in Gustaf Molander's Defiance. 'I asked Gustaf Molander about using Harriet. He looked at me and winked. 'If you believe you can get something out of her, I suppose it would be nice.' Only later did I grasp the amiable but improper insinuation in my older colleague's remark.' Bergman was also 'no little infatuated' with Andersson: 'Oh yes

we took our time when trying out costumes', he recalls. A relationship ensued. In Bergman on Bergman he expressed his admiration for the actress: 'There's never been a girl in Swedish films who radiated more uninhibited erotic charm than Harriet.' In Images: My Life in Film he extended his compliments to her acting: 'Harriet Andersson is one of cinema's true geniuses. You meet only a few of these rare, shimmering individuals on your travels along the twisting road of the movie industry jungle.'

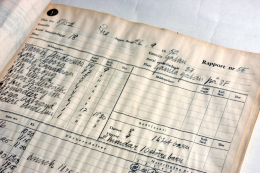

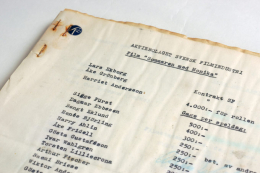

The part of Harry went to Lars Ekborg. A few year's later, Ekborg was to create another role for Bergman in The Magician; otherwise he became best known for his finely judged comic roles in the films of Hans Alfredson and Tage Danielsson, and for parts he played in various revues and stage productions. From a copy of the film's budget, still in existence, Ekborg was working under contract to SF, whilst Andersson's fee amounted to 4,000 Swedish kronor. Even when converted to current value this is a fairly modest sum for a leading role in a prestigious production: roughly 5,400 Euros, or 7,200 US dollars.

Sources of inspiration

Bergman's previous film Waiting Women ended with two young lovers leaving their irksome relatives in their house in the archipelago and making their escape to freedom in a boat. In some ways, Summer with Monika is a continuation of that theme.

Fogelström's novel had been published by Bonniers in September 1951, appearing during the spring of 1952 as a serial in the popular magazine Folket i Bild. The illustrations, by Eric Palmquist, appear to have had an influence on the way Bergman composed certain images in the film.

The archipelago setting was not new to Bergman. His films Ship to India, Thirst, Summer Interlude and Waiting Women had all featured scenes from the islands outside Stockholm. Perhaps, as a review of Summer Interlude in Dagens Nyheter put it: 'the material itself is so rewarding to explore, with its breezes, islands and waves, and its attractive young people, carefree and happy.'

Influences from Italian neorealism are apparent in many of Bergman's early works, and this film is no exception. In his book The Personal Vision of Ingmar Bergman, Jörn Donner writes with some justification that Summer with Monika exhibits clear parallels with Giuseppe De Santi's 'almost commercial sensualism'.

Shooting the film

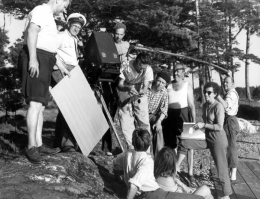

Shooting began on 22 July 1952, and a headline in Aftontidningen one week later read 'Full-blooded Harriet plays Monica'. The article described how Ingmar Bergman and his crew had set off for the coast, where they 'decamped for some peace and quiet in which to shoot the many archipelago scenes for Summer with Monica [sic] based on Per Anders Fogelström's best-selling novel.'

'On the idyllic tiny island of Sadelöga just off Utö he has found an ideal spot, at least from the point of view of being alone with his film crew. The only leisure time activity open to him after a day's work is cultivating his beard. A strange spectacle of half-naked, bearded men with Harriet Andersson in their midst greets anyone who ventures nearby.'

In Bergman on Bergman the director himself claimed that he never made a more straightforward film:

So out we went in a boat and took lodgings in the parish clerk's house on Ornö Island. As I've said, we were costing the firm nothing. There were no sets. We had fun. And the script was as sketchy as could be. Altogether it was a romantic and somewhat exhausted little gang who assembled early each morning. That was a wonderful August.

Then, just as we were getting ready to come home, it happened. To save transport costs we'd let rushes pile up over the three weeks. When it was developed we discovered that, on practically everything we'd shot, there had been a bad scratch on the negative. The message came from Stockholm that we'd just have to re-shoot the whole thing from beginning to end well, seventy-five percent of it. No film team ever shed bigger crocodile tears. We were only too happy to stay on!

Their host at Klockaregården was a living legend of the archipelago, Filip Olsson (parish clerk, pre-school teacher and folk musician). According to the report in Aftontidningen quoted above, in Olsson SF had found an invaluable geography expert who, without blinking, could conjure up the exact location they were looking for. Any stone in the southern archipelago that he doesn't know isn't worth knowing, and certainly not worth filming. One interesting aside is that Filip Olsson himself had been the inspiration for the character of Albin Olsson in Alf Sjöberg's Blossom Time.

Scenes in the city were shot on location in Stockholm and at the Råsunda Film Studios.

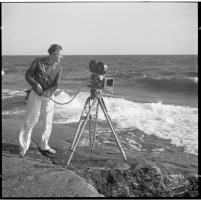

As usual, Bergman's cinematographer was Gunnar Fischer and, as ever, his contribution was brilliant. The otherwise negative review in Svenska Dagbladet declared that 'Gunnar Fischer's captivatingly rhapsodic images of Stockholm's spring mists and the glittering island paradise of summer stand alone in a special way'.

Epilogue

Shooting came to an end on 6 October 1952. Tage Holmberg and Gösta Lewin (both of whom had edited and directed a number of popular films) got the job of editing the film. A third editor was Statens Biografbyrå, the Swedish board of film censors, which cut ten metres (22 seconds) of 'brutal kicks to Harry on the ground'; and 'breast fondling after the heavy drinking scene'.

The film had its premiere on 9 February 1953 at the Spegel Cinema in Stockholm. Although the film did subsequently become a box office success, initial responses were rather lukewarm. Dagens Nyheter held the view that it was 'full of clichés: Swedish film clichés in general and Ingmar Bergman's private clichés in particular'. Robin Hood, writing in i Stockholms-Tidningen, found it hard to identify with Monika's changed mental state when the couple return from their idyll in the archipelago to the grim reality of Stockholm:

On their return to city nothing goes according to their wishes. It may well be that the conclusion rings true in a realistic sense. But it fails to do so artistically. Director Ingmar Bergman has built up something that is unfulfilled.

Fogelström's script is perhaps more consistent. The director has focused on certain personality aspects in the beginning, which has the effect of pushing others aside. At the end, Harriet Andersson displays character traits which are positively disagreeable. This is unsatisfying.

Many years on, the conclusion of Summer with Monika has divided its feminist interpreters into two camps: those who applaud the revolt of this wife and mother of a young child against a repressive system, and those who feel that Bergman forces the viewer to condemn her. The fact, as Robin Hood observes, that Monika is unpleasant is probably a key factor in the differing opinions surrounding the film, but the device was undoubtedly a significant artistic achievement for the time.

Svenska Dagbladet disapproved of the film version's shift of focus from Harry to Monika (even though its reviewer, in common with all others, heaped glowing praise on Harriet Andersson): 'Well, for a start he has stripped that little trollop Monika of all the good nature and purity of soul which, in the book at least, go some way towards counteracting her listless indolence, her irresponsibility and generally bitchy frame of mind. He has made her a bad-tempered vixen, unkempt, unwashed, uncombed and aggressive.' Given that Summer with Monika is often held out as one of its director's 'most spirited' films (it was classified, incomprehensibly enough, as a comedy by Stockholmstidningen!), it is interesting that 'Lill', writing in Dagens Nyheter, should be of the view that:

All tenderness, freshness, compassion and humour seems to have been drained from Ingmar Bergman. Gunnar Fischer's captivatingly rhapsodic images of Stockholm's spring mists and the glittering island paradise of summer stand alone in a special way, without any counterpart in the story as such. And the little sympathy that the director has left for the youngster is nothing like the sympathy he usually feels for his young women. Does Ingmar Bergman like girls so much that he is unable to portray some disagreeable traits without overdoing it?

A number of people got up and walked out during the premiere screening at Spegeln. Perhaps, quite simply, they were bored. Because, incredible as it may sound, Ingmar Bergman has made a boring film this time, sometimes faltering, for the most part sluggish, badly edited.

As mentioned above, the film went on to become a success despite the criticism. Perhaps the nudity that got past the censors had its part to play. In SF's programme for the film, Bergman himself had anticipated the debate about sin that the film sparked off.

If Summer with Monika suffered from censorship in its native Sweden, almost the opposite was true when the film launched in America. The US distributor had not only opted to translate the title to the more suggestive: 'Monica: The Story of a Bad Girl', but also as if in an unwitting gesture towards the Swedish censor 'spiced up' the film with his own footage of nudist bathing on Long Island (the same fate had previously befallen Summer Interlude, or 'Illicit Interlude' as it was first known in the US).

The manager of the Orpheum cinema in Los Angeles, where the film was premiered, was arrested while the film was being screened, and the vice squad of the Los Angeles police confiscated the film copy on suspicion of pornography. The distributor Jack Thomas was also given a fine of 750$ and sentenced to ninety days in prison. Not everything can be blamed on his creative additions: Bergman's original in itself was clearly too much for the American market. Reporting on the case against the distributor, the Los Angeles Examiner quoted Judge Byron J. Walter: 'Monica appeals to potential sex murderers [...

] Crime is on the increase and people wonder why. This is one of the reasons.'

Even after the film had been relieved of the distributor's additions, criticism in America was still fierce, with everyone pointing out the film's moral shortcomings. Films in Review, for example, called it 'a clumsily, carelessly directed sexploiter about a stupid teenager.'

Despite the phenomenon of initial contempt turning to universal praise (so typical in the case of Bergman), the re-evaluation of Summer with Monika came with remarkable speed. Following the huge success of Wild Strawberries and The Seventh Seal, many of Bergman's earlier films got caught up in the flow. Jean-Luc Godard extolled the film more than anybody else. Commenting on the Bergman retrospective in Paris in 1958, he wrote that it:

[...] is the most original film of the most original of directors. Summer With Monika is to the cinema today what Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915) is to the classical cinema. Just as Griffith influenced Eisenstein, Gance and Lang, so Summer With Monika, five years before its time, brought to a peak that renaissance in modern cinema whose high priests were Fellini in Italy, Aldrich in Hollywood, and (so we believed, wrongly perhaps) Vadim in France.

The next year, Godard's colleague François Truffaut paid a small yet well-known tribute to Summer with Monika in his own feature debut The 400 Blows, when the principal character Antoine and his friend René steal an iconic still from the film from a notice board.

In conclusion, Summer with Monika has gone down in history in Sweden as a film dear to the nations' heart, and internationally as an important part of the wave of Swedish cinematic liberation which began with Arne Mattsson's One Summer of Happiness, culminating in Vilgot Sjöman's I am Curious - Yellow. Woody Allen sums it all up rather neatly:

Less than enobling was the motive for seeing my first Ingmar Bergman movie. The facts were these: I was a teenager living in Brooklyn, and word had got around that there was a Swedish film coming to our local foreign film house in which a young woman swam completely naked. Rarely have I slept overnight on the curb to be the first on line for a movie, but when Summer with Monika opened at the Jewel in Flatbush, a young boy with red hair and black-rimmed glasses could be seen clubbing senior citizens to the floor in order to insure the choiciest, unobstructed seat.

I never knew who directed the film nor did I care, nor was I sensitive at that age to the power of the work itself – the irony, the tensions, the German Expressionist style with its poetic black-and-white photography and its erotic sado-masochistic undertones. I came away reliving only the moment Harriet Andersson disrobed, and although it was my first exposure to the director who I would come to believe was pound for pound the best of all filmmakers, I did not know it then.

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives.

- Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film.

- Stig Björkman, Torsten Manns and Jonas Sima, Bergman on Bergman, (New York: Da Capo P., 1993).

The French first discovered Bergman’s work through Summer with Monika, in 1954. “Swedish” meaning “erotic” at that time, the film was launched in a network of semi-pornographic cinemas. Its outdoor shoots and its outspokenness made a strong impression on the young writers of the Cahiers du Cinéma, who saw in it the emergence of a new aesthetic. In The 400 Blows (1959), François Truffaut thus paid tribute to the film, having Antoine Doinel and his playmate steal a very suggestive picture of Harriet Andersson at the front of a movie theater.

What struck these young filmmakers was not only the outdoors shooting and the naked body of Harriet Andersson, but also the effect of detachment, particularly at the end of the film, when the camera stops on a weary Monika.

What were we dreaming of when Summer with Monika was first shown in Paris? Ingmar Bergman was already doing what we are still blaming French directors for not doing. […] And that last shot of Nights of Cabiria, when Giulietta Masina stares fixedly into the camera: have we forgotten that this, too, appeared in the last reel but one of Summer with Monika? Have we forgotten that we had already experienced – but with a thousand times more force and poetry – that sudden conspiracy between actor and spectator [...], when Harriet Andersson, laughing eyes clouded with confusion and riveted on the camera, calls on us to witness her disgust in choosing hell instead of heaven?”

(Jean-Luc Godard, Cahiers du Cinéma, July 1958)

Apart from his affirmations in writing, Godard also made tribute to the famous last shot of Summer with Monika in his films: both Breathless (1959) and To Live One's Life (1962) end with their respective female lead looking directly into the camera (as well as by having Jean-Paul Belmondo directly addressing the audience in the former).

When interviewed on this subject, Bergman revealed his own sources:

Do you know where it has always existed? In the theatre. When actors address the audience directly and comment on the action. I resorted to this method myself in Summer with Monika. […] At that time, it was strictly prohibited.”

(Bergman on Bergman)

Summer with Monika’s cinematic revolution would thus come from an old theatrical device! Indeed, the year it was released, Bergman directed Pirandello's play Six Characters in Search of an Author, based on the same paradigm. Bergman, who directed The Three-Penny Opera in 1950, may also have had in mind Brecht's theory about Verfremdung – the distancing effect – except that Monika’s look aimed at arousing emotion, whereas Brecht’s intention was to preserve the spectator’s analytical detachment.

A great admirer of Alfred Hitchcock, Bergman may finally have been inspired by Shadow of a Doubt, released ten yers earlier than Summer with Monika. Looking right into the camera, Joseph Cotten (as murderer Charles Oakley), seems to defy the viewer to judge him.

At any rate, the shock wave of Summer with Monika’s last shot seems to have spread across Europe and the world, until today.

Other looks directed towards the camera can be found in Winter Light and Saraband, when, respectively, Märta's and Marianne's letters are read frontally, as if addressed to the viewer. These shots may have inspired similar sequences in Arnaud Desplechin’s Esther Kahn (2000) and A Christmas Tale (2008). The French filmmaker makes no secret of his admiration for Bergman, about whom he once said: “While making a film, he is the only one whom I forbid myself to think of, otherwise I would stop everything”.

Likewise, at the beginning of A Christmas Tale, Juno's keynote speech is reminiscent of Marianne’s address to the audience in the opening of Saraband, which Desplechin had just seen before he began to write his own film.

© Charlotte Renaud

[The "Legacy" section is written and compiled by Charlotte Renaud. Look here for heirs to other Bergman films.]

Distribution titles

Un été avec Monika (France)

Furyo shojo Monika (Japan)

Kesä Monikan kanssa (Finland)

Ljato s Monika (Bulgaria)

Monika (France)

Monika et le désir (France)

Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl (USA)

Sommeren med Monika (Denmark)

Sommeren med Monika (Norway)

Summer with Monika (Great Britain)

Un verano con Monica (Spain)

Die Zeit mit Monika (West Germany)

Production details

Production country: Sweden

Swedish distributor (35 mm): Svensk Filmindustri, Svenska Filminstitutet

Swedish distributor (video for rental and sale) (physical): Svenska Filminstitutet

Laboratory: Svensk Filmindustris filmlaboratorium

Production company: Svensk Filmindustri

Make up: Firma Carl M. Lundh AB

Original work: Sommaren med Monika (Novel) by Per Anders Fogelström

Aspect ratio: 1,37:1

Colour system: Black and white

Sound system: Optical mono

Original length (minutes): 96

Censorship: 081.857

Date: 1953-02-06

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2640 metres

Censorship: 081.857

Date: 1956

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2640 metres

Censorship: 081.857

Date: 1962

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2640 metres

Release date: 1953-02-09, Spegeln, Stockholm, Sweden, 96 minutes

Filming locations

Sweden (1952-07-22-1952-10-06)

Filmstaden, Råsunda (studio)

Ornö, Haninge

Boskär outside Ornö, Haninge

Borgen, Haninge

Sandelöga outside Utö, Haninge

Södermalm, Stockholm

Strömmen, Stockholm

Riddarfjärden, Stockholm

Music

Title: Kärlekens hamn

Composer: Filip Olsson (1952)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: In My Dream Garden

Composer: Gordon Rayner

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Om stråkarna kunde sjunga om Wien

Composer: Harry Lundqvist (1950)

Lyrics: Harry Lundqvist (1950)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Sankt Örjanslåten Alternative title: Örjanslåten

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Die Blume von Hawaii Alternative title: Blomman från Hawaii

Composer: Paul Abraham (1931)

Lyrics: Paul Abraham (German lyrics 1931) Nalle Halldén (Alias) (Swedish lyrics 1932)

S.S. Wilson (Alias) (Swedish lyrics 1932)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: 'O sole mio! Alternative title: Du är min sol!

Composer: Edoardo Di Capua (1899) Alfredo Mazzucchi (1899)

Lyrics: Giovanni Capurro (Italian lyrics 1898) Sven Nyblom (Swedish lyrics 1901)

Title: An der schönen blauen Donau, op. 314

Composer: Johann Strauss, jr. (1867)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Wiener Blut (waltz), op. 354 Alternative title: Wienerblod

Composer: Johann Strauss, jr. (1871)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Helan går

Singer: Harriet Andersson, Lars Ekborg

Title: Tango

Composer: Hans Wallin

Lyrics: Gardar (Alias)

Comment: Sung.

Title: Ragtime

Composer: Reinhold Svensson

Comment: Instrumental.

Critics touted Monika as "Bergman's most erotic film" for its theme of a young man's sexual awakening and scenes of nudity on an island in the Stockholm archipelago. But this summer interlude is surrounded by some of the bleakest commentary of Bergman's early cinema, in a city captured in all its shadows and empty light by the expert cinematographer Gunnar Fischer. Monika (Harriet Andersson), a restless, sexually harassed vegetable seller, and her more bourgeois boyfriend Harry take off in his father's boat for the islands. There she teaches him how to dance and how to make love, how to steal vegetables, and they dream of a family. But Borzage lovers turn into characters out of Pierrot le fou. Monika, now pregnant, becomes a denizen of the reeds. A shot of a spider web seems to announce Bergman deserting his young heroine, leaving her to founder in femme fatalism (eternal spider to man's fly) and a life of dubious freedom.

Collaborators

- Harriet Andersson

- Lars Ekborg

- Dagmar Ebbesen

- Åke Fridell

- Naemi Briese

- Åke Grönberg

- Sigge Fürst

- John Harryson

- Georg Skarstedt

- Gösta Ericsson, och porslinsvarufirman

- Gösta Gustafson

- Gösta Prüzelius

- Göthe Grefbo

- Arthur Fischer

- Torsten Lilliecrona

- Bengt Eklund

- Hans Ellis

- Ivar Wahlgren

- Renée Björling

- Catrin Westerlund

- Carl-Uno Larsson

- Hanny Schedin

- Kjell Nordenskiöld

- Margaret Young

- Nils Hultgren

- Ernst Brunman

- Sten Mattsson

- Magnus Kesster

- Carl-Axel Elfving

- Bengt Brunskog

- Wiktor "Kulörten" Andersson

- Birger Sahlberg

- Nils Whiten

- Tor Borong

- Einar Söderbäck

- Mona Geijer-Falkner

- Astrid Bodin

- Gun Östring

- Sven Löfgren

- Uno Larsson

- Marianne Lindén

- Harry Ahlin

- Jessie Flaws

- Mona Åstrand

- Gordon Löwenadler

- Anders Andelius

- Gustaf Färingborg

- P.A. Lundgren, Art Director

- Bengt Nordwall, First Assistant Cameraman

- Eskil Lindberg, Boom Operator

- Eskil Eckert-Lundin, Musical Conductor

- Gunnar Fischer, Director of Photography

- Tage Holmberg, Film Editor

- Gösta Lewin, Film Editor

- Barbro Sörman, Costume Designer

- Sven Hansen, Production Mixer

- Per Anders Fogelström, Screenplay

- Sven Persson, Re-recording Mixer

- Erik Nordgren, Music Composer

- Walle Söderlund, Music Composer

- Allan Ekelund, Production Manager / Production Coordinator

- Birgit Norlindh, Script Supervisor

- Louis Huch, Still Photographer

- Ingmar Bergman, Screenplay

- P A Lundgren