Summer Interlude

A ballet dancer reads the diary of her now dead boyfriend and memories of a summer spent in the archipelago come flooding back.

"[Summer Interlude] ... was my first film in which I felt I was functioning independently, with a style of my own, making a film all on my own."Ingmar Bergman

About the film

The period around 1950 was a difficult time for Ingmar Bergman. In 1949 his contract with the Gothenburg Municipal Theatre ran out, and with it his principal source of income. Together with his regular film producer Lorens Marmstedt he attempted to revive a theatre company (Intima Teatern), but it went into receivership following two fiasco productions (Brecht's Three-Penny Opera and a double bill of Hjalmar Bergman's A Shadow and Jean Anouilh's Medea). On top of all this, the Swedish film industry was in conflict with the government over the high rate of tax on entertainment, a situation which culminated in 1951 with a lockout and a one year stop in film production. This merely added to Bergman's financial problems. In his personal life, chaos reigned: in 1949 he left his wife and children and escaped to Paris with his lover who subsequently became pregnant. He divorced and married Gun Hagberg, who 'had no work, and now I had three families to support.' 'In my grief,' Bergman recalls, 'I wrote a film script which was given the title Summer Interlude'. The basis of the storyline dates back to the young Bergman's earliest attempts in prose. Immediately after graduating from high school he fell ill and spent his time writing 'just for the fun of it, and it was firmly intended to be kept in the drawer.' As the outside world fell in turmoil (just before the outbreak of the second world war) he wanted to write about something cheerful by way of a counter balance. His themes were 'Summer Holiday in the Archipelago' and 'First Love'. In an interview with Fritiof Billquist, Bergman describes how his ideas developed:

Then the Latin exercise book in which I wrote the story disappeared, and lots of other things happened: There were torments, crises, women without faces and the devil and his grandmother and sturm und drang, all mixed up.

One day the Latin exercise book turned up, and the pearls shone just as brightly as before. War and winter were long past.

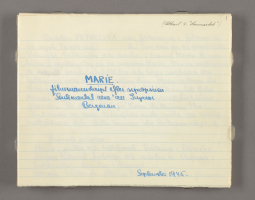

That's when the idea for the film emerged. I was going to make a film, turn the pearls into cash. Marie (as the story was called) would look after her father. So I wrote a screenplay.

The very first version of the manuscript, which appears to have been called 'Sentimental Journey' has been lost, a fact confirmed by the earliest surviving version, known as 'Marie' and dated 1945. This is a clear predecessor of Summer Interlude, despite the fact that as Maaret Koskinen has observed the title role character of this hand-written script bears no particular resemblance to the Marie of the completed film. In adapting the manuscript Bergman was helped by Herbert Grevenius, and together they turned the story into a fully functional screenplay.

Sources of inspiration

In Images: My Life in Film, Bergman describes in more detail the 'First Love' that gave rise to 'Marie' and subsequently to Summer Interlude:

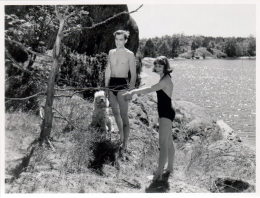

Summer Interlude has a long history. Its origin, I see now, lies in a rather touching love affair that I had one summer when my family resided on Ornö Island. I was sixteen years old and, as usual, was stuck with extra studies during my summer vacation and could only occasionally participate in activities with people my own age. Besides, I did not dress as they did; I was skinny, had acne, and stammered whenever I broke my silence and looked up reading from Nietzsche.

[... ]On the far end of this so-called Paradise Island, toward the bay, there lived a girl who was also alone. A timid love grew between us, as often happens when two young lonely people seek each other out. [ ...] Our love died when autumn came, but it served as the basis for a short story that I wrote the summer after my exams.

The name of that lonely girl was Babs. In Bergman's private archive there is a black oilcloth-bound notebook with drafts of short stories, plays and screenplays (including the first known draft of Torment), bearing a dedication to her.

All this has little more to do with Summer Interlude than the fact that Bergman's relationship with Babs was probably the experience that inspired it. And one further point – a detail, perhaps, yet a poignant one: Maaret Koskinen it is who reminds us that in Summer Interlude, an oilcloth-bound notebook appears like a ghost from the past: 'In Summer Interlude from 1951, Marie, the main female character in the film, finds a former boyfriend's diary that causes her to recall the magical summer they spent together as teenagers.' In the screenplay for Summer Interlude the incident is described as follows: 'Marie stares at the package and opens it. A book falls out of the brown envelope. It is a black, oilcloth-bound notebook, an old one. It falls open and Marie, unnerved, says Oh my goodness.' Bergman must have felt similar emotions when he found his old short story 'Marie', which had disappeared and had now reappeared. As so often in Bergman, his life and work are interwoven: the actual notebook is 'recycled' in the film, thus acquiring a special significance.

Shooting the film

Shooting began on 3 April and went on until 18 June 1950, with a few weeks' break during May. Apart from the Råsunda Film Studios and Saltsjöbaden, the film was also shot on the island of Dalarö, the scene of Bergman's youthful love affair that gave rise to the film. 'We filmed it in Stockholm's outer archipelago. The landscape had a special mixture of tempered countryside and wilderness, which played an important part in the different time schemes, in the luminescence of summer and in the autumnal twilight. [...] The filming became one of my happy experiences.'

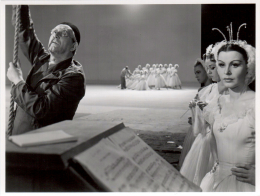

The cinematographer was Gunnar Fischer, who had to mobilise all his talents to cope with the changing light conditions. The result was dazzling: one Swedish reviewer thought that Fischer's camera work was worth 'all the bouquets in the world, bravo, bravo, bravo!' And a French review by the budding film director Jean-Luc Godard declared that Summer Interlude was 'the world's most beautiful film'. The principal role of Marie was played by Maj-Britt Nilsson, one of the most prominent Swedish film stars of the 1950s. Bergman was clearly impressed: 'The camera catches her with an affection that is easy to comprehend. She embraced the girl's story and lifted it higher with her brilliant mixture of playfulness and seriousness.' Birger Malmsten, one of Bergman's most frequently used actors at the time, was, with his romantic good-looks, perfectly suited for the role of the shy student. Malmsten often had to play more or less disguised alter ego figures for Bergman, but he had no special affection for his character in this film: 'Marie, the ballet-master and the somewhat world-weary and scabby journalist all three are projections of myself. The student boy, on the other hand, is just a coathanger. I hadn't much interest in him.'

The 'scabby' journalist was played by Alf Kjellin, who had played what is probably his best-known role a few years previously as the rebellious school student Jan-Erik Widgren in Torment. Stig Olin played the ballet master, and in a minor role as one of the dancers we find Annalisa Ericsson, perhaps best-known as a revue artiste and for her roles in light-hearted comedies.

Some of the scenes were filmed at the Royal Opera (although the institution is not named in the film), where Marie is the prima ballerina. Bergman wanted to shoot the film on location, but his team was refused entry when the management read the screenplay: the Royal Opera was not to be associated with such loose-living characters.

A minor detail of special interest to Swedish readers concerns the film's animated sequences, which were made by a very young Rune Andréasson, creator of the hugely popular cartoon character Bamse, the world's strongest bear.

Epilogue

As previously mentioned, shooting came to an end in the middle of June 1950, yet despite speedy editing by the experienced Oscar Rosander (who had worked with Bergman since his feature debut Crisis), the première had to be postponed until the following year. The financial crisis in the Swedish film industry (which would later result in a production stop) forced SF to re-schedule its releases. As a consequence High Tension, shot immediately after Summer Interlude, was premiered first. The fact that this made-to-order spy thriller took priority appears, in retrospect, somewhat ironic: it is the only film which Bergman himself has 'stamped with the skull and crossbones', and refused to allow any public screening. Summer Interlude, on the other hand, has been described by the director as the film most dear to his heart.

Summer Interlude was finally premiered on 1 October 1951 at the Röda Kvarn cinema in Stockholm. The reviews were highly enthusiastic, and it was Bergman's first critical success as a film director. Dagens Nyheter felt that 'here we have images among the most charming that Swedish cinema has produced in many years' even though the reviewer had certain reservations: 'But naturally in this Ingar [sic] Bergman film there are plenty of devices of the kind that Ingmar Bergman always amuses himself by inserting, to the annoyance of his well-disposed audience.' Lill, writing in Svenska Dagbladet, was even more enthusiastic (although not without reservations: there were 'a couple Bergman of clichés'):

For the most part, Summer Interlude is an atmospheric delight for the senses. Anything more intensive and beautiful in terms of images and sound is scarcely imaginable! Young love and the Swedish summer, and all that goes with them: joie-de-vivre and the gentle lapping of waves, passion and the warmth of the sun plus a constant undercurrent of anxiety, anxiety over death and the unknown, over autumn and darkness have been captured in a rhapsody without precedent in Ingmar Bergman's works.

Many reviewers thought they could discern a 'new' director. Robin Hood, writing in Stockholms-Tidningen, noted: 'We meet here a different Ingmar Bergman from the one we are used to. The same, and yet different. There is nothing 'strange' in the film.' Harry Schein's film column in the Bonniers Literary Magazine also bore the heading 'A new Bergman?' and he saw in this 'brilliant trifle' a director who had cast off the shackles of melancholy and metaphysics: 'Fate and the devil are still there, yet they seem so unnecessary, despite Bergman's predilections, almost as if they had crept in out of habit.'

Summer Interlude had been accepted by the Venice Film Festival in 1951, yet SF withheld it on the grounds that they wanted to test it on a Swedish audience first. (It was screened in Venice the next year, yet failed to win any awards.) The only awards it did pick up were the Svenska Filmsamfundets (later known as the Swedish Film Academy) Diploma of Honour to Bergman in 1951, and its Plaque to Maj-Britt Nilsson the following year. Despite this lack of international acclaim the film eventually got the recognition it deserved, but only on a wide scale once Bergman had become established as a bona fide auteur. The Bergman retrospective held at the French cinémathèque in Paris during 1958 played a major part in this recognition (it was then that Summer Interlude went on release in France). To coincide with the retrospective, Jean-Luc Godard wrote an article praising Bergman in Cahiers du cinéma, and despite the fact that Summer with Monika, Smiles of a Summer Night, The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries had also been screened, it was Summer Interlude on which he focused most:

There are five or six films in the history of the cinema which one wants to review simply by saying, 'It is the most beautiful of films.' Because there can be bo higher praise. [...] Five or six films, I said, + 1, for Summer Interlude is the most beautiful of films.

[...] Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of film-makers. Those who walk along the streets with their heads down, and those who walk with their heads up. In order to see what is going on around them, the former are obliged to raise their heads suddenly and often, turning to the left and then the right, embracing the field of vision in a series of glances. They see. The latter see nothing, they look, fixing their attention in the precise point which interests them. When the former are shooting a film, their framing is roomy and fluid (Rossellini), whereas with the latter it is narrowed down to the last millimetre (Hitchcock). With the former (Welles), one finds a script construction which may be lose but is remarkably open o the temptations of chance; with the latter (Lang), camera movements not only of incredible precision in the set but possessing their own abstract value as movements in space. Bergman, on the whole, belongs to the first group, to the cinema of freedom; Visconti to the second, cinema of rigour.

[...]There is a sublime moment in White Nights [Visconti, 1957] when the snow falls in huge flakes around Maria Schell and Marcello Mastroianni in their boat. But this sublimity is nothing compared to the old musician in To Joy who lies on the grass, watching Stig Olin looking amorously at Maj-Britt Nilsson in her chaise-longue, and thinking, 'How can one describe a scene of such great beauty!' I admire White Nights, but I love Summer Interlude.

The film had its US premiere in 1954. It was given the somewhat seedy title 'Illicit Interlude', and in the first version the distributor had freely and indulgently spliced in unrelated scenes of naked bathing filmed at a nudist colony on Long Island. Bizarre as this may sound, it was a fate that would also befall Summer with Monika shortly thereafter, with even greater consequences for that film.

Summer Interlude is hardly one of Bergman's best-known films, yet its creator certainly holds it in high esteem: 'For me Summer Interlude is one uf my most important films. Even though to an outsider it may seem terribly passé, for me it isn't. This was my first film in which I felt I was functioning independently, with a style of my own, making a film all my own, with a particular appearance of its own, which no one could ape. It was like no other film.'

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives.

- Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film.

- Ingmar Bergman, The Magic Lantern.

- Stig Björkman, Torsten Manns and Jonas Sima, Bergman on Bergman, (New York: Da Capo P., 1993).

- Jean-Luc Godard, "Bergmanorama", in Godard on Godard: critical writings, (London: Secker & Warburg, 1972).

- Maaret Koskinen, I begynnelsen var ordet: Ingmar Bergman och hans tidiga författarskap, (Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 2002).

Distribution titles

Un' estate d'amore (Italy)

Illicit Interlude (USA)

Jeux d'été (France)

Juegos de verano (Spain)

Juventud, divino tesoro (Uruguay)

Kesäinen leikki (Finland)

Letni sen (Poland)

Einen Sommer lang (West Germany)

Sommerleg (Denmark)

Sommerlek (Norway)

Summer Interlude (Great Britain)

Production details

Production country: Sweden

Swedish distributor (35 mm): Svensk Filmindustri, Svenska Filminstitutet

Laboratory: Svensk Filmindustris filmlaboratorium

Production company: Svensk Filmindustri

Make up: Firma Carl M. Lundh AB

Original work: Mari (Tale)

Aspect ratio: 1,37:1

Colour system: Black and white

Sound system: AGA-Baltic

Original length (minutes): 95

Censorship: 078.574

Date: 1951-04-02

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2635 metres

Censorship: 078.574

Date: 1952

Length: 2610 metres

Censorship: 078.574

Date: 1963

Length: 2610 metres

Release date: 1951-10-01, Röda Kvarn, Stockholm, Sweden, 95 minutes

Filming locations

Sweden (1950-04-03-1950-05-04) (1950-05-24-1950-06-18)

Filmstaden, Råsunda

Dalarö-Rosenön, Haninge

Sandemar, Haninge

Saltsjöbaden, Nacka

Blasieholmskajen, Stockholm

Music

Title: The Swan Lake. Lebedinoe ozero, op. 20

Composer: Pëtr Tjajkovskij (1877)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: The Swan Lake. Pas de deux Alternative title: Lebedinoe ozero, op. 20

Composer: Pëtr Tjajkovskij (1877)

Dansare: Gun Skoogberg, Göte Stergel

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Coppélia ou La fille aux yeux d'émail. Mazurka

Composer: Léo Delibes (1870)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Nynning

Composer: Eskil Eckert-Lundin

Sångare: Maj-Britt Nilsson

Title: Impromptu, piano, nr 4, op. 66, Alternative title: Fantaisie-Impromptu

Composer: Frédéric Chopin (1834)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: The Nut Cracker. Casse-Noisette. Valse des fleurs

Composer: Pëtr Tjajkovskij (1892)

Dancer: Gun Skoogberg

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: The Swan Lake. Lebedinoe ozero. Waltz

Composer: Pëtr Tjajkovskij (1877)

Comment: Instrumental.

Marie: I don't believe God exists. And if he does, I hate him.

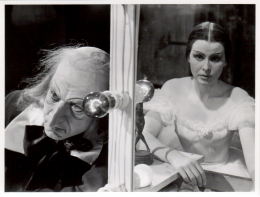

Ballet Master: Do you really think I don't understand, dear Marie? You daren't remove your make-up, and you daren't be made-up.

Ballet Master: You dance, and that's that. That's what you do. Stick to that, Marie, or you'll get into trouble. Take a look in the mirror. You look ridiculous. So do I, for that matter.

Ballet Master: Young man, I could transform you into a sugar lump. So beware.

David: Old man, I could spirit away your talent, your secret, your good name and social standing. I happen to be a journalist.

Illuminating Ingmar Bergman, Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive:

A dancer, Marie (Maj-Britt Nilsson), who is at the height (and thus sees the end) of her powers as a prima ballerina, under the dreamlike pull of memory impulsively revisits the island of her youth and, in flashbacks, her first and only love. Bergman's breakthrough masterpiece is an almost magical fusion of sunstruck elegiac love poem and dark suggestion. The latter looks ahead to The Seventh Seal and its games with death; and to Sawdust and Tinsel in its depiction of a performer struggling to see her life clearly through a mirror of humiliation. But Marie, an early Bergman heroine suffused (like the film itself) with music and dance, finally will have none of that. Jean-Luc Godard wrote that, whereas he admired other films, he loved Summer Interlude, and one can see this reflected in his films with Anna Karina - the playful cinema (cf. Bergman's cartoon interlude here, and swanlike hands dancing), the doomed lovers, the beautiful survivors. "Paradise lost and time regained" (Godard).

Collaborators

- Maj-Britt Nilsson

- Birger Malmsten

- Alf Kjellin

- Annalisa Ericson

- Georg Funkquist

- Stig Olin

- Mimi Pollak

- Renée Björling

- Gunnar Olsson

- Douglas Håge

- John Botvid

- Julia Cæsar

- Carl Ström

- Torsten Lilliecrona, Pelle, ljusmästare

- Ernst Brunman

- Olav Riégo

- Fylgia Zadig

- Eskil Eckert-Lundin

- Emmy Albiin

- Carl-Axel Elfving

- Sten Mattsson

- Marianne Schüler

- Gösta Ström

- Monique Roeger

- Gerd Andersson

- Göte Stergel

- Gun Skoogberg

- Rune Andréasson, Animation, sequence

- Nils Svenwall, Art Director

- Bengt Järnmark, First Assistant Cameraman

- Aaby Wedin, Boom Operator

- Gunnar Fischer, Director of Photography

- Oscar Rosander, Film Editor

- Sven Hansen, Production Mixer

- Sven Persson, Re-recording Mixer

- Bengt Wallerström, Music Composer

- Erik Nordgren, Music Composer

- Julius Jacobsen, Musical Arrangement

- Allan Ekelund, Production Manager / Production Coordinator

- Herbert Grevenius, Scenario

- Sol-Britt Norlander, Script Supervisor

- Ingegerd Ericsson, Script Supervisor

- Louis Huch, Still Photographer

- Ingmar Bergman, Screenplay