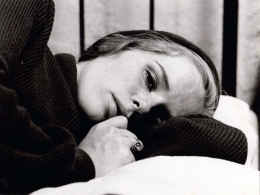

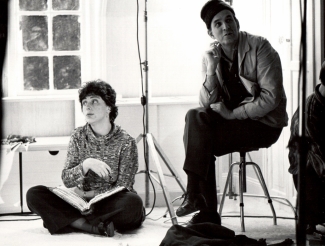

Katinka Faragó

Katinka Faragó has often been referred to as ‘Bergman’s right hand.’ As a script supervisor, production manager and producer, she has worked in the Swedish film industry for over 60 years. It was Faragó who ensured continuity throughout the filming of such classics as Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal and Winter Light. She later went on to work as a production manager at Bergman’s own production company, Cinematograph.

Katinka Faragó

Katinka Faragó has often been referred to as ‘Bergman’s right hand.’ As a script supervisor, production manager and producer, she has worked in the Swedish film industry for over 60 years. It was Faragó who ensured continuity throughout the filming of such classics as Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal and Winter Light. She later went on to work as a production manager at Bergman’s own production company, Cinematograph.

“He approached his work with a discipline and humility unlike any other filmmaker I have ever encountered.”

Faragó on Ingmar Bergman

Full bio

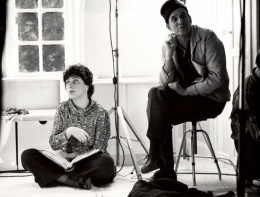

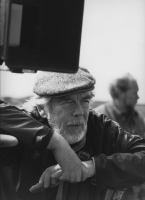

Katinka Faragó has often been referred to as ‘Bergman’s right hand.’ As a script supervisor, production manager and producer, she has worked in the Swedish film industry for over 60 years. At the age of 17, she was literally forced to work with Bergman as no one else would, and was told, ‘If he stares at you, stare back. If he spits on you, spit back.’ This was the start of a working relationship that endured over 30 years. It was Faragó who ensured continuity throughout the filming of such classics as Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal and Winter Light. She later went on to work as a production manager at Bergman’s own production company, Cinematograph.

On 16 December 1936, Katerina Faragó was born in Vienna, Austria, where her Hungarian parents were living as refugees. At the onset of World War II, her family moved once again, in 1940 finally settling in Sweden. Katinka’s father, Alexander Faragó, was an author and scriptwriter, penning the manuscript to the Swedish Loffe film series. Following her time on the set of Loffe blir polis, where as a 13-year-old girl she was given the job of watching the lead actor Elof Ahrle’s dog, she was hired as a continuity girl for the filming of Harry Martinson’s The Road to Klockrike. She has not held back in interviews when describing women’s working conditions in the film industry at that time, recalling:

When I started out as a continuity girl, an older colleague of mine gave me the following advice: Never learn stenography, or you will end up working as some man’s secretary.

Two years later, on the same day as her graduation from an all-girls’ school, she was informed that she would be working with Ingmar Bergman that summer. No one else would accept the position, and so she was literally forced to take the job. She was 17 at the time, and the film under production was Dreams. Before meeting the director for the first time, she was given the following strict orders. ‘If he stares at you, stare back. If he spits on you, spit back.’

Faragó has mentioned in interviews that everyone was afraid of Bergman at that time:

He had a shocking reputation as a director, erupting in full-blown tantrums and proving himself extremely difficult to work with. Thankfully he calmed down over the years. This naturally was an issue of trust, and he knew that I never bluffed him. Ingmar is fond of women. He understands them better than men and recognises their potential. This fact is apparent in his films.

After Dreams was completed, Faragó joined Bergman at the Swedish Film Industry for the production of Smiles of a Summer Night. She was employed by SF, where she remained for 10 years filming alongside Bergman. ‘There was no television at that time, so many films were being made. Summers were utterly chaotic,’ she explains. In total, Faragó worked for and with Bergman for over 30 years, nearly 40 if the filming of Sunday’s Children is taken into account. She worked as a script supervisor, ensuring continuity throughout the filming of such classics as Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal and Winter Light.

Faragó has described the filming of The Magic Flute and Fanny and Alexander as her two most joyful Bergman productions. In The Magic Flute she had the opportunity to work with actors from the opera world. As a script supervisor, however, her job was not a simple one; it was troublesome to edit Mozart’s music and difficult for actors not accustomed to filming to retake scenes. Alongside the filming of The Magic Flute, she produced a Making Of… entitled Tystnad, tagning Trollflöjten, (Lights, camera, action, The Magic Flute) with her husband, also the film’s producer at the time, Måns Reuterswärd. This film was her last time working as a script supervisor, as she went on to accept the role of production manager at Bergman’s own production company, Cinematograph.

Fanny and Alexander was Bergman and Faragó’s most extensive production together; pre-production alone lasted over a year. The film went on to win four Oscars, including Best Foreign Language Film.

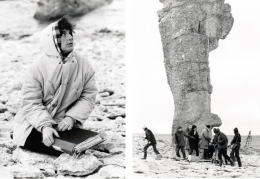

Faragó’s next big film project took place in 1985, when she worked as the production manager on Andrei Tarkovsky’s Sacrifice, which was filmed on the Swedish island of Gotland. The same year she began working as head of production at the Swedish Film Institute, a position she held until 1990, when she accepted the same role at Sandrews. Throughout the 1990s she worked with such renowned Swedish directors as Kjell-Åke Andersson and Daniel Alfredson.

In the spring of 2008 Faragó published the book, Katinka och regissörerna – 125 filmer och 55 år bakom kameran (Katinka and the directors – 125 films and 55 years behind the camera), which was written with Birgitta Kristoffersson, and is as of yet only available in Swedish.

2017 Katinka Faragó received a Liftetime Achivement Award at the Guldbagge Awards in Sweden.