Cries and Whispers

Chamber play in red about a dying woman and her sisters.

"Cries and Whispers is like few movies we'll ever see. It is hypnotic, disturbing, frightening."Roger Ebert

About the film

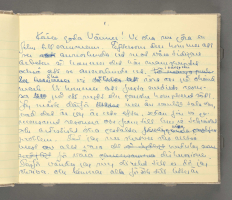

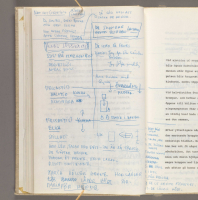

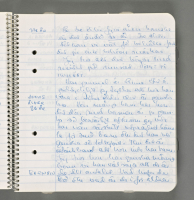

In his workbook dated 16 April 1970 Bergman wrote:

Yet the days go on, and with them a growing sense of ease, I'm shamefully at ease and I haven't actually done a stroke of work for a whole month. But now I'm in good spirits [unreadable] to start working again actually coincided with the arrival of the spring weather. It's finally, finally spring, and finally, finally, finally it's light and one can live again. So it's all set. Let's start then. Ha ha, yes! It's starting. ANNA. That's a good name, I've used it lots of times before, admittedly, but it's so good .

It's reassuring to discover that such an amazingly productive person as Bergman (with an average of one film shoot, one screenplay and two stage productions per year) can find it hard to get started once in a while, just like the rest of us. But once he had settled on the name for one of his principal characters, Cries and Whispers started to take shape in his mind. A few months later he set to work filming The Touch.

When that film was completed in spring 1971, Bergman watched it together with Sven Nykvist:

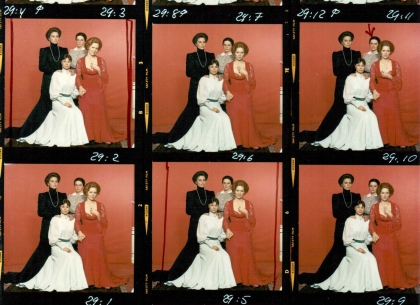

'Well, Sven', he remarked 'this was not a good film. You and I both knew it wouldn't be. But I've got another idea, something I've dreamt. I see a road, and a girl on her way to a large house, a manor house, perhaps. She has a little dog with her. Inside the house there's a large red room where three sisters dressed in white are sitting and whispering together. Do you think it could turn into a film?'

Nykvist circumspectly replied that the images sounded promising. 'Right. It's now the 4th of April,' said Bergman. 'Promise me you'll be at home in two months' time, on the 4th of June. That's when you'll get the screenplay.' And the director kept his word

.

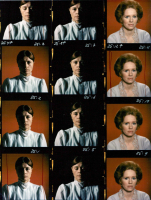

As usual he made a start on the casting while writing the script: 'I'm going to have Liv, and then there should be Ingrid, and I would very much like to have Harriet, too, since she belongs to this breed of enigmatic women. And then I want Mia Farrow; let's see if that works out. It probably will; why shouldn't it?' Mia Farrow never actually joined the cast, but the notion is an intriguing one. She was later to become the actress of choice for Woody Allen, a director who, more than any other, has paid homage to Bergman in film after film. The fact that Bergman had Farrow in his sights ten years before she and Allen worked together for the first time is a somewhat eerie coincidence.

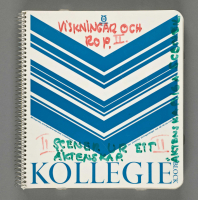

With Cries and Whispers, a project that had occupied his thoughts for so long, Bergman was eager to continue the experimentation he had embarked upon in The Silence and Persona. He was especially keen to work together with Nykvist on the colour and lighting, to 'really get stuck into the laboratory'. Another proviso was that the film should be in Swedish, despite what Bergman considered the 'wretched' state of Swedish cinema at the time. He quickly realised that funding for such a vague project would present difficulties, so he decided to go ahead and finance it himself through his own company Cinematograph. But the film turned out to be more expensive than he had first thought, and additional funds were needed. The agreed solution was that of the total budget of 1.5 million Swedish kronor, Cinematograph would put up 750,000, the Swedish Film Institute would contribute 550,000 and the remainder would be borrowed. Cash flow was also eased by the fact that Harriet Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, Liv Ullmann and Sven Nykvist invested their fees in the film: they would get a share of the profits if it was a success, but nothing at all if it was a commercial flop.

The structure of the financial package resulted in a major rumpus: the role of the Film Institute in particular caused eyebrows to be raised. Critical voices insisted that the Institute's resources would be put to better use if they were made available to less established filmmakers. When the Film Institute board arrived at its decision, it was on the tacit understanding that the film would be shot in the studios of the newly-built Filmhuset, so that its own staff would derive benefit from the project. Yet when the film crew came across a suitable manor house at Taxinge-Näsby, Bergman completely gave up on any plans to construct his interiors in the studios: 'the manor house is ideal, just as if I'd designed it myself.'

This move simply added fuel to the criticism. In response, Harry Schein, chairman of the Film Institute, penned an angry defence of his board's decision which was published on the arts pages of Expressen:

Bergman's films bring in very healthy returns from the entire world. This co-production with the director does not mean that the Film Institute is helping Bergman any more than the cinematographer and actors, who are investing their fees in this work, are helping him. It is more a case of Bergman lending a helping hand, not the Film Institute, on account of all the people who will be given a chance to work thanks to the revenues from this film. The funding that the Film Institute is providing for Bergman's film is not being taken away from anyone else. Neither is our investment in Bergman and the many people in the film industry who get work through him taking place at the cost of any other film. Quite the opposite: this investment means that the Film Institute will be better placed to fund more films than would otherwise have been the case.

Later on in the article, following this low-key introduction, Schein becomes more agitated, venting his spleen on a critical band of journalists and resentful fellow film directors:

It is typical of the state of Swedish cinema which in this respect is probably unique in the world that such a debate should arise at all. There is a petty miserliness, personal rancour, and sordid envy behind all this lobbying, behind all the posturing of newspaper editors. Young radicals in the film industry and a handful of their spokesmen have been harping on for almost a month now in the theatre columns of Dagens Nyheter and other papers trying to stir up a scandal about what, exactly? The fact that Ingmar Bergman is making a film in Sweden together with the Swedish Film Institute? In any other country you might care to name, such a piece of news would have been warmly received by all radical film lovers.

Sources of inspiration

Bergman writing in Images: My Life in Film:

'The first image kept coming back, over and over: the room draped all in red with women clad in white. That's the way it is: Images obstinately resurface without my knowing what they want with me; then they diasppear only to come back, looking exactly the same.'

As with Persona, Bergman appended a foreword to the finished screenplay, aimed primarily at his fellow workers on the film. In terms of atmosphere it ties in well with the finished film, and it also includes brooding descriptions of how Cries and Whispers was first conceived.

Many observers have tended to view the central women in the film, Agnes, Karin, Maria and Anna, as four aspects of one and the same person. Bergman has concurred with this view. For him, this is a typical device. On one occasion he referred to the film as a 'self-portrait' of his mother (who was also called Karin). Initially, his choice of words seems inappropriate can a self-portrait be anything other than a portrait of oneself? Yet it is quite possibly a conscious play on words: the concept of fusing together with another person is a recurring theme in his work.

Many years later Bergman denied that Cries and Whispers actually would be about his mother. 'That was a lie for the media. It was a spontaneous and careless remark. It was to haunt me. Since then it has always been linked to the film. Some stupid remarks one makes tend to live a life on their own. It was a lie. I said it in order to have something to say. It's very hard to say anything about Cries and Whispers', Bergman said in the documentary Bergman and the Cinema, first shown in Swedish Television in 2004.

The enigmatic title of the film was borrowed from the music critic Yngve Flyckt's description of Mozart's Piano Concerto No 14 in E flat major (K449): music which sounds, according to Flycht, just like 'cries and whispers'.

In the theatre, Bergman has staged countless productions of Ibsen, Molière, Shakespeare and Strindberg. Yet of all the world's great dramatists, Anton Chekhov has hardly featured at all in the Bergman canon. He only ever directed two plays by the Russian master: The Seagull at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in 1961, and Three Sisters at München Residenztheater in 1978. This may seem somewhat odd, since the two of them have much in common. And Cries and Whispers has been compared with Chekhov by a number of commentators, including François Truffaut: 'It begins like Chekhov's Three Sisters and ends like The Cherry Orchard and in between it's more like Strindberg.'

Maaret Koskinen has pointed out some fascinating similarities between Cries and Whispers and a prose fragment written some thirty years earlier in 1942. The film opens with a montage of clocks (the almost banal interpretation of which is that Agnes' time is up), which clearly bears comparison with the earlier writing:

So she goes up to the tall, dark grandfather clock, then to the drawing room with its two small, gilded table clocks under glass domes, decorated with shepherds and shepherdesses. She sets all the clocks in the house in motion, and now the silence is filled with the soft, living tick-tock of four clocks. The small shepherd clocks in the drawing room then strike with five tinny, ringing chimes they are in a great hurry. Before these have finished, the sound is joined by the rounded, calm and dignified chimes of the bedroom clock. Finally, five muted chimes ring out from the sombre grandfather clock.

Shooting the film

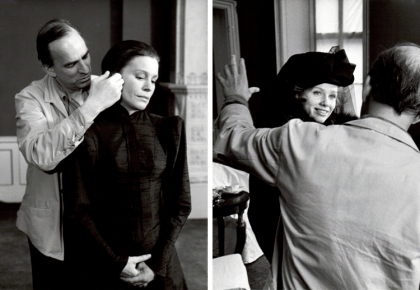

Bergman's film shoots always begin with meticulous preparation: several days of running through the script with everyone in the crew, from the actors down to the make-up assistants. It is a method he probably learnt from the theatre, and one which has worked well: he has rarely gone over budget or taken longer to shoot a film than the time prescribed. For this film, in which he himself was responsible for so much risk capital, the procedure was even more important to him than before, not least because he realised that many technical difficulties lay ahead.

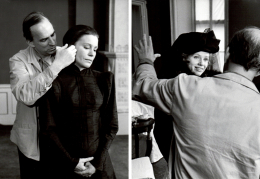

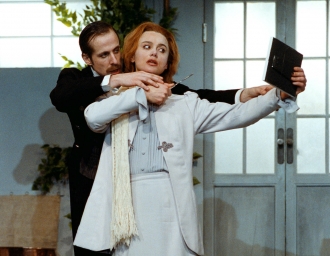

By the time shooting got under way Bergman and Nykvist 'had tested everything that possibly could be tested; not only the makeup, the hair, the costumes, but every object, wall covering, the upholstery, every inch of carpeting.' At a press conference to mark the start of filming, Bergman stressed just how important Marik Vos' costumes and scenery were, since the film is 'based on atmospheres. And Sven Nykvist's photography will be crucial to the outcome. The film is rich in close-ups the light around faces at dawn and dusk.' 'The problem', Nykvist interjected, 'is that colour film contains too much colour. If you want to show dawns and dusks, you can't simply work on the lighting, you also have to work with filters in the laboratory. It's a question of daring to question the 'rules' of colour film.' And for Cries and Whispers, Börje Lundh's make-up was even more important than usual, since the red of the sets might so easily reflect too harshly in the close-ups of faces.

The film's faithful servant, the fourth part of the composite picture, was played by the dancer Kari Sylwan, who had recently worked with Bergman in two of his theatre productions, A Dream Play and Show.

The men in the lives of these women were played by Erland Josephson and two less well-known actors in a Bergman context. Henning Moritzen is probably best known currently for his role in Tomas Vinterberg's The Celebration, but he had long been one of Denmark's most prolific actors. During the filming Bergman called him one of the best in Scandinavia, maintaining that 'he's so pleasant that you can hardly believe he is an actor

' Two years later Mortizen would play Alceste in Bergman's production of The Misanthrope at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen. Georg Årlin had played minor parts in Swedish films since 1940, but was primarily a stage actor. Bergman had directed him in a number of television plays and theatre productions dating back to 1943. Årlin, for example, played the title role in Don Juan at the Malmö City Theatre in 1955.

The film's press officer was Lars-Olof Löthwall, who has written about the film shoot in a couple of articles. In one anecdote he recalls how at the start of filming Bergman announced to the entire crew: 'On Thursday Nurse Gerd will be here to give us all an injection in our backsides. Gamma globulin. Do you know what gamma globulin is?' Nobody was allowed to be ill. Everyone had to stick to the time schedule, and to the all-important budget.

Löthwall also overheard many of Bergman's instructions to the actors, such as this one to Harriet Andersson: 'Take care in the waking up scene. Lie there for a long time with your eyes shut. We must know you're awake. We need to feel it.' Bergman also asked Liv Ullmann to 'remember that Maria is a woman who has never closed a door behind herself in her entire life

.' Although Bergman is renowned for knowing what he wants, most of this is reserved for the scenery and camerawork. His actors have often been granted major freedom to develop their own roles, although he stops short of allowing them to improvise freely. Character interpretation is clearly a complex process, or, as Bergman himself puts it: 'Explaining what you yourself intended can be bloody difficult.'

Cries and Whispers certainly counts as one of Bergman's most unremittingly pessimistic works. But in making these bleaker films, the cast and crew usually appear to have had a great deal of fun on the set. Everyone recalls this particular shoot with affection, not least the four female leads, who maintained a good deal of gently self-mocking cheer throughout.

One day, as Löthwall recalls, a banal popular song with the refrain 'you're always in a good mood when the sun shines' came on the radio. Bergman, Harriet Andersson and the make-up artist Börje Lundh started to sing along. '

The next minute they were recreating a marriage from hell on celluloid.'

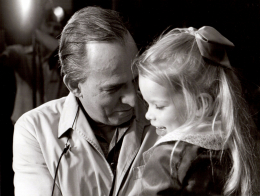

The genial atmosphere was no doubt aided by the fact that Bergman was in love and about to marry Ingrid von Rosen, who had a minor part in the film. (Two of his daughters also appear in the film: Lena Bergman and Linn Ullmann).

Yet even though the atmosphere was cheerful for the most part, it wasn't without its darker moments. At one point Bergman had agreed to do an interview with Löthwall, but at the appointed time the director complained: 'It's quite unthinkable that you could get me to talk now. I don't want to. I can't. I can't stand myself any longer. This is so difficult that I've lost the will to live.' A few moments later the cameras were rolling once more, and Bergman was completely wrapped up in the task at hand.

Moreover, during one particular take in the film, Bergman wearily summarised the process as follows: 'It's the same old film every time. The same actors. Same scenes. Same problems. The only thing that distinguishes one film from another is the fact that we're all getting older...'

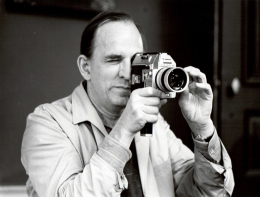

Cries and Whispers was the first film in which Bergman used a zoom lens, a technique that was extremely popular at the time (although it remains unclear as to whether or not it was actually Bergman who decided to use it). Sven Nykvist has recounted how the zoom effects, which Bergman generally disliked, had to take place discreetly: 'With my left hand I managed some small, almost indiscernible zoom-ins. If I did it when the camera was moving, then Ingmar didn't notice and since he was pleased, I didn't say anything.' When Bergman finally realised what was happening he let it go, since it did produce the results he sought. Nykvist also tells how Bergman wanted to sit as close to the camera as possible so as to maintain eye contact with the actors: 'It was a problem at times. He and the assistant cameraman, who was responsible for focusing, would fight over the best position. But Ingmar was so thin that he could sometimes manage to squeeze in between the legs of the camera and sit on the floor right under the lens. Then he was happy.'

Epilogue

Cries and Whispers was screened outside the main competition at the Cannes Film Festival in 1973, and Bergman gave his first ever press conference outside Scandinavia. It was a polite affair in which he fielded questions such as which part of himself he devoted to the theatre, and which part to films. 'I'm a complete person', was his response.

On its release in Sweden, the film provoked a good deal of criticism of Bergman in general. The broadsheet Dagens Nyheter, for example, accused him of being sentimental at the expense of social and political conviction. Even though the film was set in the past, it ignored any historical context. A review in the communist newspaper Gnistan ("The Spark") reads:

This is a world event, so they say. Just like Volvo and Swedish vodka, Bergman is a saleable product in the global marketplace. [...] Ingmar Bergman is one of this country's truly reactionary artists. He would never, as many other artists did, take a stand on behalf of the people of Vietnam. He is very hostile towards the proletarian theatres that are beginning to spring up. In acting circles it is a well known fact that he thinks that workers' theatre is bad theatre. He would never sink to such a low level. Bergman makes art for company directors and their like, a sort of Playboy art. It always involves a little nudity, something a bit shocking and a few emotional entanglements. Made for export.

The film's US distributor was, oddly enough, Roger Corman, the legendary and prolific producer of B- and horror movies. But it was a fortunate move for both parties, since the film was such an amazing success. The money invested by Bergman, his colleagues and the Swedish Film Institute's reaped major dividends. A few years later Bergman was asked just how much money he had earned from Cries and Whispers, but he was unable to be precise. 'All I know is that it was like playing a one-armed bandit. You put a coin in the slot, the wheels started spinning, and suddenly three oranges lined up in front of you. Money just gushed out of the machine...'

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives.

- Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film.

- Maaret Koskinen, I begynnelsen var ordet : Ingmar Bergman och hans tidiga författarskap, (Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 2002).

- Sven Nykvist, Vördnad för ljuset: om film och människor, red. Bengt Forslund, (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1997).

- "Viskningar och rop ett enormt äventyr", Upsala Nya Tidning, 7 September 1971.

- Lars-Olof Löthwall, "Sådan är han Ingmar Bergman", Allers, no 34, 1972.

- "Hela världen får se halva 'äktenskapet'", Expressen, 27 August 1974.

- "-Tack ska ni ha, sa Bergman - Ja jag var dödsförskräckt", Sydsvenska Dagbladet, 20 May 1973.

- Gnistan, no 11, 1972.

While Cries and Whispers may have inspired the theme and tone of Woody Allen's Interiors (1978), it has probably also influenced Another woman ten years later, through the figure of the Mother, coming from the garden in a white dress, as an elegant ghost from the past.

More violent is Karin's vaginal mutilation in the middle of the film, which seems to have made some impression on Michael Haneke and – in a different register – William Friedkin.

© Charlotte Renaud

[The "Legacy" section is written and compiled by Charlotte Renaud. Look here for heirs to other Bergman films.]

Distribution titles

Cries and Whispers (USA)

Cris et chuchotements (France)

Gritos e sussuros (Brasil)

Gritos y susurros (Spain)

Hvisken og råb (Denmark)

Kuiskauksia ja huutoja (Finland)

Lagrimas e suspiros (Portugal)

Schreew zonder antwoord (The Netherlands)

Schreie und Flüstern (West Germany)

Seoty a vykriky (Czechoslovakia)

Suttogások, sikolyok (Hungary)

Szepty i krzyki (Poland)

Viskningar och rop (Norway)

Production details

Production country: Sweden

Swedish distributor (35 mm): Svensk Filmindustri, Svenska Filminstitutet

Swedish distributor: (video for sal and rental) (physical): Svenska Filminstitutet

Laboratory: FilmTeknik AB

Production company: Cinematograph AB, Svenska Filminstitutet, Liv Ullmann, Ingrid Thulin, Harriet Andersson, Sven Nykvist

Aspect ratio: 1,66:1

Colour system: Eastman Color

Sound system: Optical mono

Original length (minutes): 91

Censorship: 111.192

Date: 1972-08-05

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2500 meter

Release date: 1972-12-21, Cinema, New York, USA, 91 minutes

Swedish premiere: 1973-03-05, Spegeln, Göteborg, Sweden, 91 minutes

Camera, Malmö, Sweden

Spegeln, Stockholm, Sweden

Music

Title: Cello Suite no 5 c-minor

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

Title: Mazurka no 13 a-minor opus 17 no 4

Composer: Frédéric Chopin

Maria: You've changed. Is there someone else?

David: There always is. Besides, I thought the problem didn't interest you.

Maria: It doesn't.

David: Come over here Maria. Look at yourself in the mirror. You are beautiful. Perhaps more so than in our time. But you've changed. I want you to see that you've changed. These days you cast rapid, calculating, sidelong glances. You're gaze used to be direct, open, and without any disguise. Your mouth is an expression of discontent and hunger. It used only to be soft. Your complexion has become pallid, you use make-up. Your fine, broad forehead now has four creases above each eyebrow. You can't tell in this light, though you can in daylight. Do you know how they get there? Indifference, Maria. And this fine contour from the ear to the chin, it's no longer quite so evident. That's where complacency and indolence reside. Look here, at the bridge of the nose, why do you sneer so often, Maria? Do you see, you sneer to often. Do you see, Maria? Beneath your eyes, those sharp, barely visible wrinkles of boredom and impatience.

Maria: Do you see all that in my face?

David: No, but I feel it when you kiss me.

Maria: You're making fun of me. But I know where you see it.

David: And where would that be?

Maria: In yourself. Because we're so alike, you and me.

David: You mean the selfishness, the coldness, the indifference?

Isak, the priest: If it be that you gathered our suffering in your poor body and have borne it with you through death. If it be that you meet God there in that other land. If it be that He turns His face towards you. If it that you will know the language of Our Lord. If it be that you can speak to the Lord, if it be so: then pray for us. Agnes, dear child, listen to what I tell you now. Pray for us who are left on this dark and dirty earth beneath and empty and cruel sky. Lay your burden of suffering at the Lord?s feet and ask Him to pardon us. Ask Him to set us free at last, from our anxiety, our weariness and our profound doubt. Ask Him for a meaning to our lives. Agnes, you have suffered so inconceivably and so long, you must surely be worthy to plead our case.

Karin: Don't touch me! Don't come any nearer! I abhor any form of contact.

Agnes: Can you hold my hands and warm me? Stay with me until the horror is past. It's empty all around me.

Karin: Not a soul would do what you ask. I'm alive, and I want nothing to do with your death. Perhaps if I loved you, but I don't love you.

Karin: Let's keep to our resolutions.

Maria: Why shouldn't we, dearest?

Karin: I don't know. Everything is so different now.

Maria: We've come closer to each other.

Karin: What are you thinking?

Maria: About our conversation.

Karin: No, you're not.

Maria: I'm thinking that Joakim is waiting, and he hates that. Why do you suddenly call me to account for my thoughts? What is it you want?

Karin: Nothing.

Maria: Then you won't be hurt if I say goodbye now.

Karin: You've touched me, have you forgotten?

Maria: I can't remember every little remark, or be held responsible for them. Look after yourself and give my love to the children.

Anna, reading Agnes' journal: Wednesday the third of September. The tang of autumn fills the clear still air but it's mild and fine. My sisters, Karin and Maria have come to see me. It's wonderful to be together again like in the old days, and I am feeling much better. We were even able to go for a little walk together. Such an event for me, especially since i haven't been out of doors for so long. Suddenly we began to laugh and run toward the old swing that we hadn't seen since we were children. We sat in it like three good little sisters and Anna pushed us, slowly and gently. All my aches and pains were gone. The people I am most fond of in the entire world were with me. I could hear their chatting around me. I could feel the presence of their bodies, the warmth of their hands. I wanted to hold the moment fast and thought, Come what may, this is happiness. I cannot wish for anything better. Now, for a few minutes, I can experience perfection. And I feel profoundly grateful to my life, which gives me so much.

Ryan DeRosa, Pacific Film Archive, 1996:

Cries and Whispers depicts the final day of Agnes (Harriet Andersson), who lies in bed with cancer. Her most dear ones, her sisters, Maria (Liv Ullmann) and Karin (Ingrid Thulin), and a companion, Anna (Kari Sylwan) watch over her. In a film as formal as a clock's tick, Bergman restricts his palette to colors of blood, his close-ups to the image of the soul. The four women want strength to face life, to overcome fear, to remove the curtain from behind which they look and admire, but do not go forth to touch. They are the same person in different stages of realizing that to love is to empty oneself of desire; to forgive oneself; to hear fully the cry of the present through the searing whispers from the past; to imagine a love that gives without knowing how to heal or provide rest, yet is vast and vigilant, because that is life's meaning: to be saved by giving one's body and soul.

Collaborators

- Ingmar Bergman, Director, script and narrator

- Sven Nykvist, Director of Photography

- Siv Lundgren, Film Editor

- Katinka Faragó, Script Supervisor

- Marik Vos, Production Designer

- Greta Johansson, Costume Designer

- Börje Lundh, Make-up Supervisor

- Cecilia Drott, Make-up Supervisor

- Britt Falkemo, Make-up Supervisor

- Karin Johansson, Costume Designer

- Gunilla Jakobson, Property Master

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Music Composer

- Frédéric Chopin, Music Composer

- Owe Svensson, Production Mixer

- Lars-Owe Carlberg, Production Manager

- Ann-Christin Lobråten, Assistant Production Designer

- Lars Karlsson, First Assistant Cameraman

- Tommy Persson, Boom Operator

- Louis Lindberg, Color Timer

- Anders Bergkvist, Key Grip

- Ragnar Waaranperä, Key Grip

- Gerhard Carlsson, Gaffer

- Stefan Gustafsson, Gaffer

- Sven Fahlén, Re-recording Mixer

- Bo-Erik Gyberg, Still Photographer

- Harriet Andersson, Agnes

- Kari Sylwan, Anna

- Ingrid Thulin, Karin

- Liv Ullmann, Maria and Maria's mother

- Anders Ek, Isak, priest

- Inga Gill, The storyteller

- Erland Josephson, David, doctor

- Henning Moritzen, Joakim, Maria's husband

- Georg Årlin, Fredrik, Karin's husband

- Linn Ullmann, Maria's daughter

- Malin Gjörup, Anna's daughter

- Rossana Mariano, Agnes as a child

- Lena Bergman, Marria as a child

- Monika Priede, Karin as a child

- Ingrid Bergman

- Arne Carlsson, Other Crew

- Hans Rehnberg, Other Crew